Photo courtesy of George Eastman House on Flickr.

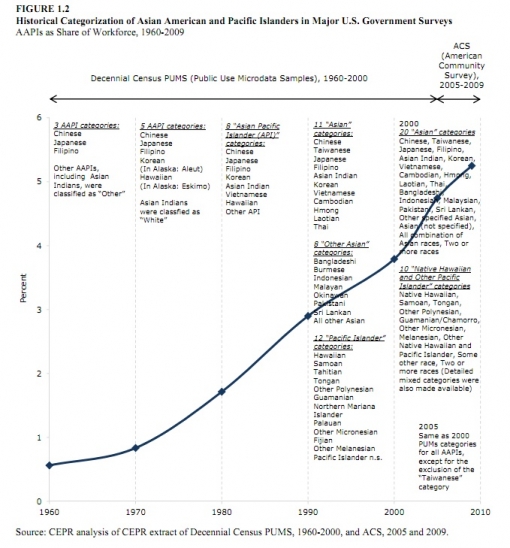

The US census has come a long way since its first year in 1790 when it categorized Americans as free white males over 16 years old, free white males under 16, free white females, all other free persons, and slaves. But this progress has had its fair share of identity crises and frustration due to the mandate to declare one’s nuanced background through a simple check-marked box -- as well as the fact that these checkmarks came to dictate the size of the federal pie each community received. If you were an Asian American filling out the Census in 1960, you would only have had three ethnicities from which to choose: Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, or an undifferentiated “other” category. Mixed-race with one white parent? Then you were part of “the race other than white.” Mixed-race with no white parent? Then you’d be categorized as your father’s race. In 1970, you would have been given two additional options: Korean and Hawaiian. Asian Indians were counted as “white.” The 1980 Census added Asian Indian, Vietnamese, and an “other API” category.

While race is arbitrary, these changes were not. South Asians actively organized and appealed for the census change -- despite internal resistance. According to Asian American studies professor Susan Koshy, a small yet significant proportion of the population wished to remain in the “white” category, for reasons “ranging from discomfort with siphoning off benefits that should be directed toward economically disadvantaged minorities, to desire to avoid the stigma of minority status, to confidence that middle-class status offered sufficient protections against discrimination, to fear of a backlash from American-born minorities for appropriating special benefits, to fear of hostility from whites for seeking preferential status.”

AAPI categories expanded further with the 1990 Census, including 19 categories for Asians and 12 for Pacific Islanders. A movement throughout the 1990s culminated with further revisions, and the 2000 Census further allowed for detailed mixed-race categories that included Asians and Pacific Islanders. Hawaiians, among other Pacific Islanders, were removed from the Asian/Pacific Islander category and given a separate category of “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.”

“This was a long hard struggle, where Native Hawaiians presented compelling arguments that the Census standards must facilitate the production of data to describe their social and economic situation and to monitor discrimination against Native Hawaiians,” said Professor J. Kehaulani Kauanui, Associate Professor of American Studies and Anthropology at Wesleyan University. Prior to the disaggregation, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander data was easily overwhelmed by the data of the general Asian American population.

Loa Niumeitolu, community wellness advocate for Community Health for Asian Americans (CHAA), feels this problem directly in her work. “Many agencies receive funding for Pacific Islander communities under their API title, but they do not serve Pacific Islanders or have a single Pacific Islander staff or board member in their organization,” Niumeitolu wrote on the CHAA website. “The Asian part of API is privileged over ‘PI’, the Pacific Islander tag along at the end.”

For Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, the conflating of data has historically caused problematic lumping of ethnic groups in census data, neglecting the needs of starkly different communities. Does the lumping of AAPIs still exist? How has the conversation shifted in regards to racial classification and how are organizations perpetuating generalizations or stereotypes?

Assembly Bill 1088 in California, just recently signed on October 9 by Governor Jerry Brown, will improve data collection for AAPIs by requiring various State Departments to disaggregate data for Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders groups, consistent with the categories of the US Census. The bill was authored by assemblymember Mike Eng, who said, “This bill is necessary to show not only the ethnic diversity that exists within those racial groups, but also to inform policy-makers and advocates how to better tailor programs to work more effectively for those who need them.”

Janine Moa, a community organizer for Pacific Islanders, adds, “With disaggregated data, it’s easier to tell how well, or not so well, we’re doing … We need the data to show those in power the need. Otherwise, we get lost in the shuffle. And that’s not just for us, but for refugees, and more recent immigrants.”

Moa, who grew up in Tonga and Hawaii, sees her community's needs as most similar to those of Cambodian or Vietnamese populations in Oakland, while Kauanui feels that issues facing Native Hawaiians, American Samoans, and Chamorros from Guam are more akin to those of American Indians and Alaska Natives. When Moa learned about South Asian communities also being underrepresented in Asian American data, she felt she could relate.

“This is really about people negotiating identity from a form,” said Elaine Howard, a Tongan activist in Oakland. “Without a box to check, it’s like we’re not included, that we haven’t existed for decades. For so long we didn’t know who we were. People think we’re Latino! It just feels good to know where you’re from and that others do too. Because who really wants to be an Other?”

With the increase of mixed-race populations, it is also increasingly difficult to allocate resources purely along racial lines. Some oppose the continued proliferation of categories; as writer Corey Takahashi explains, “broadening the racial bandwidth could reduce counts for minority populations, and thus endanger hardwon -- and in many cases, very recently enacted -- social and political gains.” Plus, on a more individual level, multi-racial options are said to force people both to quantify and fracture one’s sense of self.

In the past few years, Howard has noticed more Asian American organizations that serve Pacific Islanders, even though they don’t have the AAPI name. “The scene is changing. It’s more inclusive. To me, AAPI is such a throwback term. People whose heritage are from Asia or from Pacific Islands, it’s so diverse, even to lump all Asians together seems ridiculous.”

Howard adds, however, that “getting rid of the term would be hard for Filipinos. They would lose their category! During my work with the census as a liaison to the PI community, I would ask Filipinos and they’d say we’re Asian but we’re different; we’re PI too.”

Or, if you’re like the writer of this article and you’re a Chinese American New Zealander -- then the AAPI acronym works just perfectly.

* * *

Make your eyes go bendy with more Census data here:

Additional facts

Asian population details

NHOPI

Report by the Center for Economic Policy and Research

Comments