On a bright Monday in May of 1975, New York City’s Chinatown saw the largest protest in its history, and one of the largest ever by Asian Americans. Thousands of seamstresses, waiters, cooks, and students came out in force to demand an end to police violence. A reminder came over the Chinese radio that morning, and shopkeepers hung handwritten signs in their windows: “Closed to Protest Police Brutality.” At 9 am, most of Chinatown was shut down — an unprecedented sight on a business day — and a mass of bodies began marching from Mott Street down to City Hall.

The catalyst for the protest came the month before, when a young man named Peter Yew was beaten and strip-searched by the police without cause. Prior to that, a series of police shootings and stop-and-frisks had shaken the Chinatown populace. Activists of the burgeoning Asian American movement used the Yew incident as a spark, unleashing Chinatown’s dormant political strength. For years, the young organizers had been studying the historical and social context of Chinatown, and formulating the new identity of “Asian American” through culture, activism, and analysis.

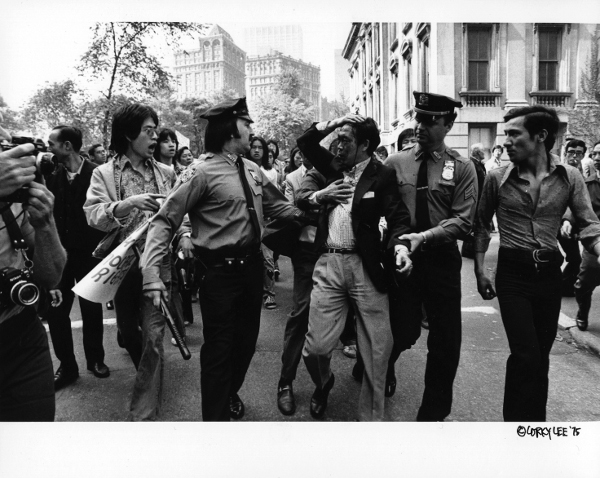

“This protest was a Chinatown version of Ferguson. There was no looting, but there was civil unrest. It had to be the first time ever,” recalls photographer Corky Lee, who captured the protests on camera. As groups like #APIs4BlackLives and CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities add Asian American voices to the movements against police brutality today, revisiting the spring of 1975 shows that police brutality and activism were, in fact, central to the formation of Asian American identity.

For weeks before the May rally, community groups amplified the story of the police’s attack on Yew through mimeographed bulletins and street corner agitations. The activists linked policing to grievances around housing, employment, and social mobility; they offered rally as an outlet for all of it.

Yee Ling Poon, one of the people behind the march, recalls that “This was not a family outing. People knew they were confronting the police. It was very tense.” Protesters held poster boards printed with the words “Minorities Unite! Fight for Democratic Rights!” and unfurled a huge banner reading “END ALL OPPRESSION! Fight Racial Discrimination! End Police Brutality! Support Yew’s Case!”

The mass of people moved down Park Row in rows six to eight bodies wide, a mix of young people with jeans and feathered hair and Chinatown elders in floral print blouses and suits. At its peak, the demonstration swelled to some 10–20,000 people. Chinatown, perpetually caught in the popular imagination as insulated and complacent, had come out in force literally to knock on the door of City Hall.

A group of representatives was allowed into City Hall to meet with a Deputy Mayor and Police Commissioner, but none of the younger movement activists were included. Upset by this, a faction of the mass broke off and staged an impromptu civil disobedience. A thousand people blocked the busy traffic on Broadway, staying long into the afternoon. Throughout the day, fights broke out between police and protesters, and a bloodied middle-aged Chinese man was rushed away from the scene. Some protesters stayed until ten that night, a vigil against a police force and government they had grown disillusioned with.

“Police Brutality Victim,” 1976 © Corky Lee, All Rights Reserved

The era that produced the Yew protests was one of the most fraught in the 130-year dance between the all-white NYPD Fifth Precinct and the Chinatown populace. A rise in both organized crime and police repression caught the neighborhood’s citizens in its crossfire.

The 1965 Immigration Act raised the national quota of Chinese allowed to immigrate from about 100 per year to 20,000. Nearly a quarter of this influx listed New York’s Chinatown as their destination, and the population grew sevenfold in the two decades following. As historian Peter Kwong chronicled in his book “The New Chinatown,” this boom strained the neighborhood’s economy: it gave rise to the garment industry and an array of new restaurants, but also ensnared those industries in cutthroat price competition. New York itself was in the midst of an economic slump that lasted through the 1970s, an era of limited city-funded social services.

Tongs, the associations that traditionally held power in Chinatown, saw an opportunity to both extract money from these new immigrant businesses and to employ some of the idle youth in the neighborhood. Kwong writes that gangs, made up of teenage and twenty-something youths, would “protect gambling houses, deal in drugs, extort money from merchants, and collect loans and protection money from theaters, nightclubs, and massage parlors.”

In July of 1974, the NYPD appointed a new captain to the Fifth Precinct, Edward McCabe, to crack down on this activity. In the year following his appointment, police conducted 11 raids on suspected gambling establishments and constant stop-and-frisk searches of suspected youth. An Asian Americans for Equal Employment bulletin later coined this the “Chinatown Hassle,” noting that the vast majority of these stops were groundless.

Past midnight on December 3, 1974, two police officers were sent to follow a group of youths — alleged gang members — into the Jade Chalet restaurant on Worth Street. Inside, the youths began to harass the officers, and the jeers escalated into a brawl. One officer fired his gun, killing a bystander, 31-year-old Tsu Yi Wu, and injuring another, 29-year-old James Leeong. Neither were involved with the youths. Four of the youths were arraigned in Criminal Court, and the other four, because they were under 16 years old, in Family Court. The attorney for the four older teens accused the officer who fired of being drunk. The incident soured relations with the police force, and led to some minor protests.

Though the May 1975 protests were a shock to the mainstream media — “New Militancy Emerges in Chinatown” proclaimed a June New York Times headline — they were in fact built through years of research and organizing. The activists of the Asian American movement, an upwelling of organizing and cultural work that spread across the country from the late 1960s through the early 1980s, had been preparing for a flashpoint like the Yew case.

“Asian American” didn’t exist until 1968, when it was coined by the Third World Strikes at SF State and UC Berkeley (until then, “Oriental” was still the prevailing term). The Asian American movement was made up of a new generation: largely college-educated and attuned to the political currents of the day, many of them from families that came under the 1965 Immigration Act. Frustrated by the War in Vietnam, an absence of political and cultural representation, and the poverty and lack of social services in Asian communities, they turned to radical politics. Following the lead of groups like the Black Panthers, they saw their issues not as isolated, but as part of a larger global structure of America’s racialized capitalism and racial imperialism.

The Asian American movement wanted to bring this revolutionary perspective to the streets of Chinatown. In the early 1970s, hoping to take their analysis a step further, some students at New York’s City College began a study group on Marxist-Leninist-Maoist theory. They called themselves Workers Viewpoint Organization (WVO), and began to theorize an Asian American response to the global revolutions they were witnessing. In the spring of 1974, WVO saw an opportunity to recruit and mobilize a mass base.

Construction had just begun on Confucius Plaza, a housing project providing lower- and middle-income apartments for Chinatown and the Lower East Side. The circular brick tower still dominates the neighborhood’s skyline. Though the project was federally funded, and there was a need for jobs in Chinatown, the DeMatteis corporation contracting the job did not hire a single Asian worker. WVO and community members recognized this as part of the systematic racism in the construction industry.

WVO members established Asian Americans for Equal Employment (AAFEE), a group focused on civil rights and social justice organizing without the openly communist rhetoric. They opened a small office at 1 East Broadway and began circulating a bilingual community newspaper. Learning from the techniques of Black civil rights organizers in Harlem, AAFEE protesters staged civil disobediences, jumping over the fence of the construction site and halting work; they held rallies in front of the site, and used Chinese language media to mobilize the community.

Those young activists became the community leaders they felt were lacking. Floyd Huen, who came to New York from the Bay Area to organize with the Chinatown movement, jumped the fence at the construction site and landed in jail. A team of lawyers, who would later go on to found the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, were ready to bail them out. In Huen’s eyes, the success of the rallies was “because of the void in political infrastructure. We made a call, and — boom!”

The protesters saw themselves as a righteous force against the combined power of the state and corporate interests. AAFEE circulated a special bulletin in June of 1974 critiquing the combined forces of the police, government, and DeMatteis Corporation:

Hundreds of police have been involved with full back-up of horses, cars, communications trucks and scooters. While the real criminals still roam the streets, over fifty have been arrested in the Confucius Plaza demonstrations, on the call of Dematteis [sic] Corporation. Government officials and others have been trying to “cool off” AAFEE through token job offers. A big stick and a small carrot seems to be the government and industry position at this time.

But AAFEE Has a potentially bigger stick — the support of the masses in the community and the determination to struggle until we win, until all discrimination in the construction and other industries is completely abolished.

By the end of that long summer of arrests and pickets, the contractors relented and hired 27 minority workers, most of them Asian. This group of fierce and dedicated young people — many of them in their twenties — showed that they could rally their community and win concessions from a major corporation. They were savvy enough to code their radical politics into a rhetoric that moved Chinatown into action.

When a young engineer named Peter Yew was beaten by the police in April of 1975, the news spread quickly around the community. Yew, unlike the Jade Chalet youths, was an educated young adult with no criminal record or gang affiliation to. He was a 27-year old student in architectural engineering from Brooklyn. Eyewitnesses said he was a bystander to a traffic incident who, because he vocalized his disagreement with the police’s conduct, was grabbed by officers and dragged into the Fifth Precinct station, where he was beaten and strip-searched. The police said that he assaulted an officer. He was later brought to a hospital and treated for contusions and a sprained wrist.

In Yee Ling Poon’s analysis, “movements can’t be created, in a sense. They’re based on small events — you make it big.” Poon had come to New York from Hong Kong with her family in 1970, and she immersed herself in the movement, studying the history of the Chinese American experience. The event crystalized the frustration she felt watching her parents work long hours just to survive, a pattern that had entrapped Chinese Americans for a hundred years. “The first group that was angry was us, knowing the history,” she says. “It turned out other people agreed with our anger.”

AAFEE saw a way to build off the victory of Confucius Plaza. “Confucius plaza was more narrow, centered around civil disobedience,” says Huen, who served as a marshal in the May rally. The Yew case touched upon the feelings of a wider audience. He recalls AFFEE distributing “thousands and thousands of bilingual leaflets,” and culling media support.

AAFEE called a rally on May 12, Yew’s court date (a week before the mass march of May 19), and asked the neighborhood establishment, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, to co-sponsor. The CCBA declined. The organization, a coalition of some sixty businesses, was aligned with the Kuomintang and anti-communist, and feared causing friction with the city government with such a brazen protest.

To the CCBA’s surprise, AAFEE’s rally attracted some 2,500–5,000 people, and received prominent coverage in the New York Times. Adding to the flames, Captain McCabe was quoted in the press dismissing the demonstration as “resentment because of gambling arrests.” The AAFEE organizers again approached M.B. Lee, the chair of the CCBA, whose daughter was one of the younger activists in Chinatown. He recognized the conviction and idealism of the group, and promised CCBA support for a second rally.

Because most of the businesses and family associations in the neighborhood had ties to the CCBA, they followed the call and gave their workers the day off. That support was crucial to turning out the 10-20,000 of the May 19 rally. In addition, that negotiation elicited broader sympathy in Chinatown for the young organizers of AAFEE, who showed that they had not written off the older generations.

Within a few months of that mass rally in 1975, most of the protesters’ demands were met. Five days after the May 19 protest, Captain McCabe was removed as the head of the Fifth Precinct. On July 2, a grand jury dismissed the charges against Yew. The next day, that grand jury indicted the two officers who beat Yew on misdemeanor charges of assault and official misconduct.

While the May 1975 protests resulted in quick concessions, its longer legacy remains an open question. The protests catalyzed the emergence of a new power in a rapidly changing Chinatown, showing a younger generation breaking the hegemony of the older establishment. The Asian American movement continued on through the 1980s, creating a body of institutions and culture that would articulate that new identity. Asian Americans for Equality is now a large nonprofit focusing on housing development and social services.

New York Chinatown has not seen a massive response to police brutality since. In part, this is due to the softened tactics of the Fifth Precinct in the wake of the 1975 protests. The NYPD established an auxiliary force of unarmed, Chinese American foot policemen.

But incidents of police brutality continued. “I saw the barrel of a gun from a cop plenty of times,” says Don Lee, who skipped class as a junior high school student to join the 1975 protests. “Things were tough.” In the years he was at high school and at NYU, Lee recalls police repeatedly stopping him without cause and asking him to produce identification.

In 1995, sixteen-year-old Yong Xin Huang was shot and killed by police in Sheepshead Bay for carrying a pellet gun. Though a more horrifying case than Yew’s, the largest protests that followed numbered in the hundreds. Poon, who now practices immigration law in Chinatown, notes that: “Chinatown is harder to organize now. There’s a big influx of mainland immigrants who speak Mandarin, who have no legal status. It’s hard for them to come out. The same tactics would not work — they don’t have a history here yet.”

The evolving Chinese diaspora in New York is continuously misunderstood by the NYPD. In 2012, the Department of Homeland Security teamed up with the police to raid an alleged organized crime establishment on East Broadway. People in the building expressed outrage, saying they were playing friendly games of mahjong. In 2014, the police bloodied 84-year-old pedestrian Kang Wong because he did not respond to their orders; it turned out he speaks only Cantonese and Spanish. Organizations like the Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence, or CAAAV, established in 1986 response to the murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit, have responded to cases like Wong’s with direct actions, press conferences, and advocacy.

Meanwhile, Black Lives Matter has brought policing to the national consciousness, and thousands of Muslim and South Asian individuals and community centers fight against surveillance in the wake of 9/11. The patterns are the same as Chinatown in 1975: systemic economic and political unease find an outlet in policing, remaking the city along racial lines.

A look back at the protests of 1975 offers a chance to redefine our conception of Asian America. Police brutality becomes a fundamentally Asian American issue, and Asian American becomes an identity rooted in activism, in struggle. The protests were a success “not because we had power,” recalls Poon. “You need to fan the flames, unleash anger. When you can tap into that — that’s when you have a movement.”

Comments