Photos courtesy of Tammy Kim.

When my brother suggested Christmas dinner in South Philly, I immediately heard the rap from The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, even though Will Smith's character hails from the west. I'd imagined South Philadelphia in stereotypical terms -- through "Cousin Will"’s inner-city reveries and the hermetic, all-black community portrayed in Code of the Street. What I found instead was a Vietnamese strip mall at 10th and Washington, where my brother and I shared a holiday meal of phở and bún.

Encounters with South Philadelphia involve constant revision. In recent years, Asian immigrants from Vietnam, Nepal, China, and Cambodia have come in large numbers to form a visible part of commercial and neighborhood life. And their children have entered the public schools, troubling the black-white binary of a segregated city.

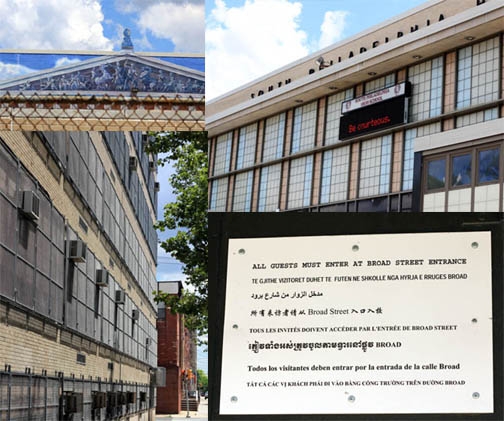

A changing street in South Philly.

South Philadelphia High School is a gargantuan concrete block off Broad Street. Five floors of windows are covered in metal grates, and a few ostentatious murals depict allegories of learning. At the main entrance a sign loops red, pixellated messages like "Celebrate Diversity." A notice is posted in eight languages on the building's north side.

The exterior of South Philadelphia High School.

Here, brothers Duong Nghe Ly and Duong Thang Ly began their sophomore and junior years, respectively, in fall 2009. They'd arrived with their parents from Vietnam, after some 20 years of waiting and wading through immigration applications. The Asian student population of South Philadelphia High, mostly new immigrant, has hovered around 20% in recent years, and the school, despite its otherwise nefarious reputation, has become well known for its ESL program.

Even the Ly brothers don't really know why the attacks occurred. Why, in December 2009, nearly 30 Asian students were violently assaulted, 13 of them rushed to the emergency room. Or how an incompetent, and, as it turns out, uncertified, principal reigned complacent through years of hostility.

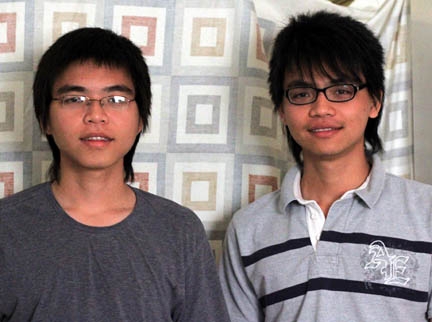

Duong Nghe Ly, left, and Duong Thang Ly, right, in their South Philly home.

"If you look straight at the situation," Duong Nghe explains, "you would think this is just racial tension between blacks and Asians, but you can also think about it in a more institutional way. The school allowed all these stereotypes and misunderstandings to happen, to continue to escalate, without addressing them, without bringing groups together to understand each other."

The events at South Philadelphia High School transformed the Ly brothers into activists, though Duong Thang disclaims the label. Having experienced the violence firsthand, they joined dozens of other Asian students in an eight-day boycott and brought legal and political pressure upon the school district, building a movement along the way. "Our friends who had graduated before we came told us about the violence. ... They didn't want to reconcile. They just wanted revenge and more revenge," Duong Thang says. "But we chose another path."

The interior of Phở Hoa restaurant, where Duong Thang, 22, works part-time.

On a recent Friday morning, I sat with the Ly brothers at their half-moon dining table, in a row house not far from South Philadelphia High. Duong Nghe is slender and boyish, a skeptic as compared to Duong Thang, who is gentle and has a quick smile. Duong Nghe is the outspoken one, the one who has received national awards for his work and will soon attend the University of Pennsylvania, two rocky years of American life barely under his belt.

Their home bears familiar signs of bicultural life: school medals and graduation photos are hung centrally, betraying familial priorities; the couch abuts a Buddhist altar dusted with fresh incense ash. Their father, who works at a Chinese grocery store, and their mother, who works odd jobs when her hips aren't acting up, have already left for the day.

Snyder Avenue in South Philly.

At 19, Duong Nghe talks about racism, school policing, political corruption, and gentrification with the authority of a longtime organizer -- and has battle scars to boot. Through Boat People SOS, one of the community groups that supported the students' boycott, he is working on an ethnic studies curriculum to politicize Vietnamese youth. He believes such curricula can mitigate violent impulses, as students come to "understand each other's stories and background," including "how we got here, what our ancestors did in the past, and how we contribute to this country."

"America is much more complicated than I expected," he says. "I had a Hannah Montana vision where everyone gets along. With big houses, beaches, and swimming pools."

A broken fantasy, to be sure, especially in South Philadelphia. But the Ly brothers are remaking the neighborhood as they go, fashioning a new, less brittle reality.

Look for Helen I. Hwang's story on bullying and anti-Asian violence at South Philadelphia High School in Hyphen's forthcoming Survival issue.

Comments