Two weeks ago in The American Prospect, Kenyon Farrow wrote of “Occupy Wall Street’s

Race Problem.” He attacked what he perceives to be

a movement dominated by “white protesters”

as well as the rhetoric used by white progressives, citing a protest sign that read "DEBT = SLAVERY" as well as a quote by writer-politico

Naomi Wolf expressing her anger that she, a well-dressed white woman, could be

arrested for simply standing on a street corner.

Farrow was evidently annoyed by the hyperbolic signage and Wolf's lack of

self-awareness, but it sounds like he hasn’t spent much

time with OWS. In the early days of the movement, I might have echoed his easy

criticism of privileged white grad students and limousine liberals, or punks

and anarchists stinking up a park with bad hygiene and immature politics. But as

I’ve learned through direct involvement, Farrow's critique -- that Occupy Wall Street’s offensive

rhetoric alienates African Americans and other people of color from the

movement -- draws far too many conclusions from too little evidence.

One

hears many such excuses, many distancing memes: it’s too white, those people are so privileged, they don’t

speak for me. Even bracketing the illogic of applying “privilege”

to militant activists drenched in rain and freezing temperatures, these are

flimsy apologetics. Occupy Wall Street has already inserted itself into every conversation in America, and it's this level of rhetoric -- we are the 99% -- not the odd poster, that should concern us. If you don’t agree with the messaging, it’s on you to change it. If you feel it’s

not diverse enough, add your body to the mix. In this consensus-based process, participation is our most valuable critical faculty.

One should also recognize the instability of OWS as observable spectacle. It’s

an evolving, self-made, messy space whose signs, statements, and local demographics change

day to day, hour to hour. This is, on the one hand, a beautiful strength, a real chance for imaginative dialogue in what Slavoj Žižek rightly calls a deeply ideological time; on the other hand, as The New Yorker's Hendrik Hertzberg cautions, we have yet to see whether this young, loosely organized movement will bear

political or policy fruits. Each trip to Zuccotti Park means a new reveal: one day it's a cacophony of agendas, yet overwhelmingly white; the next, it's single message and as diverse as New York City itself. This was true at dawn on Friday, October 14, when tens of thousands of us gathered

in Zuccotti Park to prevent New York City from evicting the occupiers under the

guise of “cleaning.” It has also been true many Fridays since, the park “occupied”

by South Asian activists protesting war and police brutality.

Racial-justice activists will be irritated by white leftists, who still seem to dominate the nightly General Assembly meetings. But all of us will be annoyed and offended by plenty of different people we encounter at OWS. This is inherent to the jagged, sloppy process of horizontal movement-building, and it shouldn’t

be a dealbreaker. While I believe the space must be diverse to succeed, I also appreciate the white occupiers who, in a brave exercise of genetic

prerogative, put themselves at the front lines of interactions with police and the wintry elements. To be sure, Zuccotti Park would have been wiped

out a long time ago if the encampment were all brown and black radicals. More

people of color need to lay claim to OWS, as do the immigrants’

rights and anti-war movements -- and here we East Coasters can learn from Occupy Oakland -- but it's important to remember the real, disproportionate threat posed by law enforcement to racial minorities and non-US citizens.

Moreover, the story of OWS cannot be told simply through what is seen. Among its many

behind-the-curtain committees are a People of Color Working Group and an Immigrant

Workers’ Rights Solidarity group. Terrific, critical coverage of OWS is readily available at

Racialicious and the infrontandcenter blog, and even the New York Times has noted the increased

involvement of people of color, namely the critical intervention by South Asians for Justice to force revision of the Declaration of the Occupation of

New York City. This rather dramatic episode, first recounted by Manissa

Maharawal, meant vocalizing racial-justice concerns to a General Assembly crowd

of 400. Thanu Yakupitiyage, who was present that night and is active in several

OWS working groups, recalls, “Learning to

articulate the nuances around our politics was really important, particularly

in a movement where lots of different people are getting involved. And communities

of color need to be involved. You can’t talk about

the greed of corporations and financiers without talking about, for example,

how the financial and housing crises specifically impact communities of color.”

As Rinku Sen has written in The Nation, the question is really, "How can a racial analysis, and its consequent agenda, be woven into the fabric of the movement?" The answer begins with activists of color, whose participation at Zuccotti Park itself or

in the less apparent, tireless gatherings animating OWS serves as the best retort to Farrow’s

critique. The Immigrant

Workers' Rights Solidarity group, in which I've been active, has met many consecutive Tuesday nights.

Our membership and attendance have grown at a rate any community organizer

would envy -- and with little in the way of centralization. Ten minutes with

this group should allay any skepticism about OWS’s commitment

to issues of difference. It is one of the most diverse, committed coalitions

I've ever been a part of, and we are already injecting the movement with the

concerns of immigrants and low-wage workers. Despite my cynical resistance to

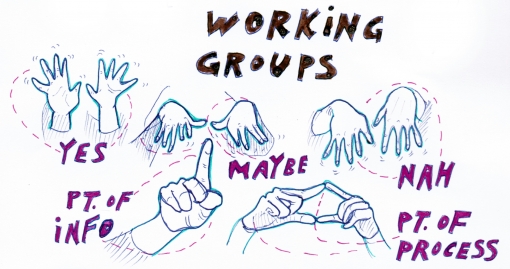

the hand signals sometimes used in

consensus-based decisionmaking (and maligned brillliantly by Steven Colbert), I was enthused enough the other night to

twinkle my fingers -- both in agreement and protest.

tammy.kim [at] hyphenmagazine.com%22%3E%20image%20%3C/a%3E">

Comments