Photo: Seoul International School 1997 Yearbook

I cried on the first day of school. I'm not talking about pre-school, or even elementary school. I cried on the first day of my junior year in high school. Let me explain.

When I was sixteen, I left everything I knew in Utah – my high school friends, my snow-capped Wasatch Mountains, my beloved 130 pound Golden Retriever, Nugget – and moved with my parents halfway across the world to South Korea. I think if I had moved to any other country, it would’ve been easier to adjust. But it wasn't easy. I was a long-haired, Pearl Jam-listening, flannel-wearing Korean American from one of the racially-whitest, politically-reddest, humanly-weirdest states in the US. A Korean American who couldn’t speak ten words of Korean, who never saw ten Koreans at once, who had never even set foot in a Koreatown, to be suddenly surrounded by millions of them, their language, their stares, their unfamiliarity that was supposed to be familiar, but wasn’t. At my going-away party in Salt Lake City, a white friend asked me, “How does it feel to go back to Korea?” I cringed at the word “back” -- it meant I was only a temporary sojourner in the place that I thought was my permanent home, returning to a place that I never knew. That’s why I kind of looked forward to moving to Korea -- I thought, maybe I’ll finally find full acceptance in the homeland of my parents. But the moment I arrived, and saw the rows of Hyundai and Samsung apartment buildings tower over me like distant, disapproving relatives, I had a feeling acceptance would be elusive.

My new school didn’t help either -- in fact, it made it worse. It was called Seoul International School, but it definitely didn’t seem all that international. All I saw were Korean faces. Faces that spoke Korean to each other or accented English or both -- like, “Esther, [jibber jabber jibber jabber] ohmygodriiiii?” EstherGraceSusan’s mouth was often covered in black lipstick, while PeterDavidJohn’s hair was often gelled and spiked. For the first week, I ate lunch in the office of SIS’s college counselor. Eventually, I ate lunch with the “foreign” kids. Sitting with Egyptians, Canadians, and Indians, I was the only ethnic Korean at the foreigners’ table in a school in Korea. Yeah. Meanwhile, the EsterGraceSusans and PeterDavidJohns looked at me, I felt, with utter contempt. I had no idea why. All I knew was I didn’t belong. Anywhere.

Photo by: Shuttergenic

Photo by: Shuttergenic

I soon realized that all the Korean kids at my school were rich. Not the kind of rich that I saw in the upper avenues of Salt Lake City, but a whole other level of wealth that I had never encountered. I saw kids lighting 10,000 won bills on fire at lunch. I heard stories of weekend binges at clubs drinking something called “soju” in an area of Seoul called Gangnam (now made famous by PSY). I sometimes took the city bus from my apartment to SIS, then weaved my way around the parked black limousines, their drivers leaning against the door, smoking, waiting for school to end and their bosses’ kids to climb in. I remember looking into those limos. I couldn’t see what was inside, but I had an inkling of what lay beneath -- wealth, connections, power. But all I saw were tinted windows, impenetrable and indecipherable, like the hangul on all the signs I couldn’t read.

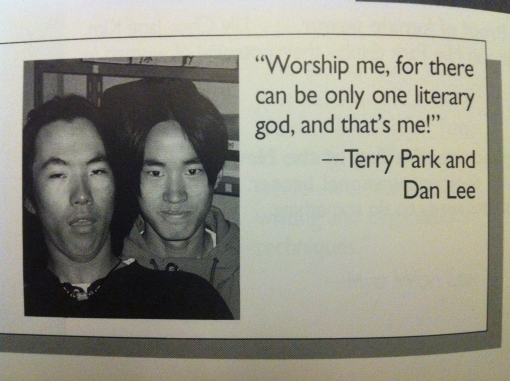

Then I met Dan. He was like many of the other Korean kids who had moved around the world their entire lives -- Switzerland, Canada, Hong Kong. But in a school where I threw myself into the role of the weird theater-creative writer guy, I saw him as different. Scrawny and zit-faced, obsessed with the character “Armand” from Anne Rice novels, Dan wrote clever short stories about rebel youth who cheated the system, sometimes caught sometimes not. These stories resembled his own constant run-ins with school authorities. Among fellow juniors, Dan was the court jester whose constant stream of wisecracks often made him the center of attention. I can still remember his laughter careening like shotgun blasts from the back of the school bus where I sat alone, sometimes next to his shy cousin Sam. With me, though, Dan was deferential. He dutifully fulfilled his role as my apprentice, acceding to my re-imagining of our school’s literary magazine Kaleidoscope. I appreciated Dan. I felt like he was the closest thing to a kindred spirit in a school, in a country where I didn't feel like kindred. I saw him as my protégé. At the same time, I was a little jealous of him -- the ease in which he switched between English and Korean, the ease in which he laughed with the foreigner kids and the Korean kids. And then I found out that he wrote a song for some Korean rock singer named Kim Gun Mo who, as it turns out, is famous. I knew Dan was a good writer, but I didn’t think he was that good. It was like Dan had a foot in the black limo that I could only gaze at, without comprehension.

Photo: Seoul International School 1997 Yearbook

Photo: Seoul International School 1997 Yearbook

A few years later, as I started to get my acting career off the ground in New York City, I heard that a new hip-hop group, Epik High, was making a big splash in Korea. Their lead MC went by the handle Tablo. I soon learned that Tablo was none other than Dan “Armand” Lee. My reaction: “Um, what?” I looked Tablo up on the Internet. His bio was a bildungsroman of a young artist faced with an assortment of obstacles impeding the full flowering of his genius -- teachers, a stern father, depression. Obstacles easily relatable by many South Korean youth. His only outlet, supposedly, was hip-hop. Reading his bio, I felt like I was reading one of his short stories from Kaleidoscope. And no wonder Dan’s writing skills were polished -- his bio stated that he received a BA and an MA in creative writing from Stanford in only three and a half years. This fact was underscored anytime there was an article or interview with Dan. Attach the word Stanford or Harvard or Yale next to someone’s name, and a successful career is pretty much guaranteed in Korea (or in the US). I was simultaneously impressed and jealous. Like the theater exercise that Dan and I learned from our beloved theater/creative writing teacher at SIS in which a scene is created with still bodies and active imaginations -- an exercise called “tableau” -- Dan successfully crafted and embodied the role of a Korean hip-hop star.

Photo: nautiljon.com

In the spring of 2006, I crafted and embodied my own characters in an off-Broadway solo show, 38th Parallels. I thought that this was the vehicle that would launch me to stardom. It didn’t. Disappointed, I entered a PhD program at UC Davis. At 27, I failed as a performance artist, so I thought I could find fortune and fame as an Asian American studies professor (yes, I was clueless about academia). Meanwhile, Dan’s career took off. He began performing in sold-out concerts in Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and New York City. While spending part of the summer of 2007 in Seoul, I saw Dan everywhere on TV. In one of my favorite Korean shows, Non-Stop. In a car commercial. In talk shows, praised for his Stanford degrees, his non-accented English, his inventive music. Back in Davis, I asked my students to name their favorite Asian American performer -- and I was shocked to hear that name again. Every time I heard his name, I was reminded of everything I wanted to be and the assets that I lacked. He was the one being studied and praised by my own students. All I could say was, “I went to high school with Tablo.” I was as bitter as winter kimchi.

But in 2010, the name Tablo quickly began to signify something else entirely. In May of that year, a group of Korean “netizens” (a portmanteau comprised of internet and citizen) formed an online forum called TaJinYo, an abbreviation in Korean for the phrase “We demand the truth, Tablo.” They accused Dan of falsifying his Stanford records. Its members went so far as to say he never attended Stanford, a charge that was completely bogus, for I had seen Dan at Stanford with my own eyes when I visited a mutual friend. I understood the socio-economic climate from which this anger emerged. Netizens were a sign of an expanding and vibrant civil society that for decades suffered under intense censorship under a succession of US-supported South Korean military dictatorships. Now, everyday citizens were taking advantage of the technology provided by the most wired country in the world and progressive news sites like Ohmynews to have an impact on their country in a way that was unthinkable just a couple decades prior. They could expose and attack the practices of the elite, including some high-profile cases of forged diplomas, often from universities in the West, out of reach for most Koreans except those able to afford to send their kids to English-language institutes or international schools like SIS. The way in which the TaJinYo movement grew in numbers and ferocity struck many foreign observers as strange. Many English teachers in Korea also used this opportunity to describe all Koreans as “irrational” -- nevermind that TaJinYo bore some resemblance to the anti-Obama "birther" movement in the US.

Moreover, gyopos, or overseas Koreans, have at times been a target of jealousy and suspicion by Koreans in Korea. In the first few decades after the Korean War, a brain drain drove many class-privileged, highly-educated, and highly-skilled Koreans like my father to immigrate to the US and other Western countries to study and help build their Cold War economies. These Koreans were often branded as traitors who abandoned a nation reeling from colonization, national division, occupation, war, and extreme poverty to find social mobility elsewhere, sometimes in those very countries that brought these conditions to Korea. Some offspring of these post-1965 immigrants have returned to Korea to find fame as pop stars without having to serve in the military, a treasonous act in a masculine garrison state where service is mandatory for all men. Most notable is Korean American rapper Yoo Seung Jun, whose career prematurely ended because he evaded military service. So it wasn’t surprising, especially given the climate of intense scrutiny of Korean celebrities in Korea, when some netizens set their sights on a gyopo rapper, a product of an elite international high school in Korea and an elite university in the US. There was nothing that Dan could do to convince these people that he actually attended Stanford, not even after an MBC crew followed him to Palo Alto, interviewed administrators and former professors, and even recorded a close-up of his transcript. In a society where lying, cheating, and forgery by government and economic elites made the “truth” something that could easily be fabricated, Dan was caught up in a trap by proxy. He and his family even received death threats. Clearly, TaJinYo had gone way too far. So, why then, didn’t he reach out to his fellow SIS alums?

That was partly revealed this past April, when Joshua Davis of Wired published an in-depth article about the controversy that included an interview with Dan. Like something out of the South Korean film Oldboy, Davis traced the origin of the controversy to high school -- my high school, SIS. In fact, I was told by a common friend who went to both SIS and Stanford with Dan that after he achieved stardom, he refused to talk to most of his former classmates -- presumably, she thinks, because we knew what he was like in high school, which would’ve disrupted the narrative that he carefully crafted for himself. Davis came to the same conclusion, but with a more startling revelation. The person whose blog posts ignited TaJinYo was none other than the shy cousin whom Dan ignored in the school bus, the one voted “Most Studious” in our senior class: Sam.

I won’t go into Sam’s accusations, since they’re quoted at length in Davis’s article. But Sam's comments made me think back to the black limos at SIS. While Dan and I are both from the Korean diaspora, he (and Sam) had mobility, access, and knowledge that I didn’t possess, and that positioned us differently. Not that I ever wanted to be a pop star -- I wanted to be a famous actor in the US. More than that, I wanted recognition. Dan had that (along with the perils it brought). That’s what I was jealous of. Recognition was all I ever wanted, and never found, in either the alabaster landscape of Salt Lake City or the neon-lit streets of Seoul. It’s something I’ve finally found -- or rather, re-defined for myself -- here in the Bay Area. One could say I’m one actor in a dynamic Asian American cast using our un/still bodies and active imaginations to create a series of “tableaux.”

Photo by: Shuttergenic

Photo by: Shuttergenic

I recently downloaded Dan’s solo album Fever’s End, which not only documents the pain and frustration Dan went through with the TaJinYo controversy, but also his ability to harness his considerable writing and rapping skills to persevere. In short, if “Tablo” is a well-crafted fabrication, it’s only because of the remarkable talents of its author. I am proud of my protégé, who never was my protégé. That was a fictional role that I made up too, in order to feel less alone in a country that never felt like home. And that’s the true worth of a story -- not whether it’s “true,” or helps us find fame and fortune, but if it helps us survive and become better people, and maybe even create a better world.

On October 10, the Seoul District Court sentenced eight TaJinYo members. “Mr. Lee” and two others will serve ten months in jail while “Mr. Song” and five others will serve two years of probation. On October 19, after a three-year hiatus, Epik High released its seventh album, 99. I haven’t heard it yet, but I’m sure it’s just as good as all of Dan’s other work, going all the way back to his emo-licious poems and rebellious stories for Kaleidoscope. A few days ago I dusted off the issue we co-edited together and found a short essay he wrote entitled “Forgiveness.” The last two sentences contain a message that the jailed members of TaJinYo, Dan, Sam, and I could heed from a high school junior whose future had yet to be written: “Sometimes anger and frustration flood our minds. We must let forgiveness be a life-jacket for love.”

***

Special thanks to Dr. Sylvia Nam for her invaluable feedback and support.

Comments