When Malaka Gharib, founder of the Washington, DC, zine The Runcible Spoon, is told that her publication has been spotted in the halls of the federal government, she chuckles in disbelief: “Really?” Her reaction is understandable: The zine, focused on new and healthy eating in the district, collages adorable illustrations and magazine cutouts alongside articles titled “Food So Fresh It Should Be Slapped: Celebrating the Season’s Best at the Dupont Circle Farmers Market” and recipes for homemade mustard.

That this free eight-page, black-and-white photocopied rag would be read by the nation’s stodgy power brokers seems dubious.

After all, the 24-year-old created the zine to be decidedly egalitarian: “We’re about democratizing the DC food scene and bringing it — quite literally — to the streets,” the mission statement reads.

I later discover Treasury (where I’d heard The Runcible Spoon has been spotted) is not only a government department to which you pay your taxes. It’s also a vintage boutique in the district’s hip U Street district where Gharib lays out copies.

The populist ethic of The Runcible Spoon is a historic hallmark of zines, loosely defined as small-circulation, cheaply produced independent publications that are often free or low cost. Zines exploded in the 1980s, due to the proliferation of copy centers and affordable computers. The early ’90s saw another resurgence of the medium, when young feminists in particular used it as a tool for activism. This was all, however, before the World Wide Web juggernaut killed many a printed word.

As many publications today flee for the digital hills, Gharib’s fetching year-old zine is a hopeful sign that not only is print not dead, but, as many in the scene attest, it’s thriving. Statistics on zines are hard to pin down, partly because of the informal and transitory nature of the genre, but many enthusiasts say the field is doing just fine in the 21st century.

If anything, zinesters say the Web has resparked interest in their medium by making it easy for readers to find zines across the world to match their interest: Rick Kitagawa, a zine maker, notes that up to 75 percent of his sales are international, thanks to the Web. Some are even dipping their toes into the digital publishing world by means of websites such as issuu.com that allow entire issues to be posted in their original format and flipped through (Gharib uses Issuu’s widget to display her zine at therunciblespoon.info). And interest in zines remains high; attendance to and sales at SF zine Fest have increased steadily since the annual festival started in 2002, according to Kitagawa, one of the event’s organizers.

With society awash in 24/7 Internet connectivity and ads, the time may actually be ripe for the humble medium, according to Daniela Capistrano, founder of the POC zine Project, which promotes zines by people of color. “Right now young people are swimming in consumer culture,” Capistrano says. “There is always a backlash against passive states of consumption, so what we are experiencing right now is an appreciation of DIY activities like zine making, urban gardening, knitting, tools and equipment fabrication. The act of considering your thoughts, the layout and execution of your own zine on your own terms is very liberating.”

Indeed, it was partly in reaction to her day job as a blogger (for the anti-poverty nonprofit One Campaign) that Gharib created The Runcible Spoon. A lifelong magazine lover, she missed the thrilling tangibility of print magazines, and she maintains that the zine conveys her identity to readers in a way that a website can’t.

The idea was to give the district’s food bloggers a physical space to display their work, promote their blogs and celebrate the area’s robust food scene with an emphasis on home cooking and using local, sustainable ingredients — all with a hearty dash of quirky fun. “I wanted to go back old-school and hoped to God that people still cared about zines like that,” she says. “I know that I do.”

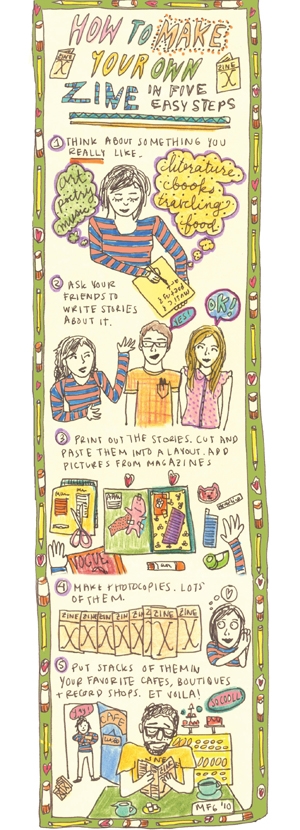

Gharib started her first zine (about indie music) at age 14, and then, as now, production involves a pair of scissors, tape, colored pencils and a stack of old magazines. An issue is completed in one day on her dining room table. The zine’s title comes from Edward Lear’s nonsensical poem “The Owl and the Pussycat,” which features an imaginary eating utensil.

Gharib produces the issues once a season and distributes them in boutiques, cafes and other spaces where her target audience — the district’s food-curious young professionals — congregates.Cathy Chung, owner of Treasury, affirms copies are snapped up quickly and says the appeal is “that it’s local, doesn’t have an advertising agenda, and the layout is really appealing. Local food has been discussed but not in such an accessible and fun manner.”

Indeed, Gharib positions her zine as a counterpoint to the frequently snobbish foodie movement. Part of that effort involves introducing more obscure Asian food to readers: one recent article, for example, covers nyonya, a Malaysian specialty derived from recipes passed down through generations. And having grown up in a predominantly Filipino community (Gharib is of Filipino and Egyptian descent), Gharib has made it her personal crusade to bring Filipino food to the mainstream.

But she acknowledges the challenges of making Filipino food, ahem, palatable. “It doesn’t look very appetizing,” Gharib says. “We don’t have any star dishes like pad thai or pho. We have pancit, which is just stir-fry noodles, which isn’t that captivating.”

And what do zine producers make of the hand-wringing over the state of the print media industry? The pressures are entirely different. Capistrano points out that financial gain isn’t of paramount importance in the zine world; people create regardless of the economic climate. And costs are lower: Gharib spends about $200 at a copy center to print 400 of each issue, in addition to small batches of surreptitiously printed-at-work copies.

The charm of zines, however, seems to lie in the premise that out of humble materials comes an utterly unique product. Gharib hopes readers will display her zine in their homes or keep copies handy in their kitchens. Ultimately, she wants to see The Runcible Spoon become a full-sized color magazine, where each issue is like a cookbook. “We want the zine to feel like a beautiful handmade gift that you wouldn’t want to throw away,” Gharib says. Lovers of print and lovers of food — not to mention home cooks fed up with food-splattered laptops — are sure to agree.

Lisa Wong Macabasco is Hyphen’s managing editor. She last wrote about Asian American women’s experiences with abortion.

This was a story from The Throwback Issue. To read the full issue, subscribe to Hyphen or pick up a copy at a newsstand near you.

Comments