Sadako Kashiwagi cherishes a certain knitted charcoal-gray sweater she’s worn for more than 40 years. It was a gift from a store owner who had fallen on hard times and had to close shop. At the time, she and husband Hiroshi were just scraping by.

“It was given to me when I was working at a school library,” she said.

Working hard and raising three young sons, even borrowing money at times, Sadako and Hiroshi, now 78 and 89 years old, endured, which was certainly nothing new for the couple.

Both grew up in Placer County, CA, east of Sacramento, where Japanese American communities sprouted from the agricultural industry. Hiroshi’s family owned a local fish market, while Sadako’s parents worked as farmers.

Not everyone was accommodating. Sadako said the community was hostile against Japanese Americans. Hiroshi said there were signs put up to discriminate against “Japs.”

Their lives were uprooted when the United States declared war against Japan in 1941. Japanese nationals and American citizens of Japanese descent faced heightened suspicions of disloyalty and treason.

Not long after, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, calling for the secretary of war to “protect against espionage” and avoid “sabotage to national defense material.” This resulted in the imprisonment of more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent under the guise of national security.

Though they did not know each other at the time, both Hiroshi’s and Sadako’s families were taken to the Tule Lake internment camp in northeastern California.

The couple at a pilgrimage to Tule Lake in 2004. Courtesy of the Kashiwagis.

The couple at a pilgrimage to Tule Lake in 2004. Courtesy of the Kashiwagis.

To add to their plight, Tule Lake happened to be the most overcrowded internment facility; it held more than 18,000 people in 1944, more than any other internment camp.

However, both families stood strong in their beliefs. Hiroshi, 19 at the time, refused to answer a "loyalty questionnaire" given to Japanese Americans to declare their allegiance to the American government and willingness to serve in the US armed forces.

Hiroshi became one of hundreds branded a "No-No Boy” for his refusal. As a result, he was separated from other internment camp inhabitants along with others who had not answered the questionnaire in a satisfactorily “patriotic” manner.

Photograph by Andria Lo

Photograph by Andria Lo

Sadako’s father refused to volunteer when the US Army visited the internment camp to recruit soldiers. FBI agents arrested him and hundreds of other protesters and transferred them to a detention center in Santa Fe, NM. Sadako’s father was held for 18 months, hundreds of miles away from his family.

“It was horrific for everyone,” said Sadako, who was 8 years old when forced into internment. “There was a certain stigma attached to us, that we were not normal, regardless of the circumstances.”

After three years of internment, Sadako worked her way through school, taking classes by day then mopping the classroom floors afterward. She graduated from San Mateo High School, then Sacramento State University with a degree in education. After graduation, she taught home economics at a school in Berkeley.

Photograph by Andria Lo

Photograph by Andria Lo

It was at a nearby Buddhist temple where she first met Hiroshi, who had earned his bachelor’s degree at the University of California, Los Angeles, before enrolling in a graduate program at UC Berkeley.

They bonded over their shared childhoods in Placer County and the dark times their families faced at Tule Lake. “We were comfortable with each other. We had that [internment experience] in common,” Sadako said. “I felt like I could be honest with him.” They married in 1956 and juggled their careers as librarians with raising their three kids.

Even during those meager times, husband and wife conveyed to their children how fortunate they are to have a free and prosperous life. “We had very limited choices,” Sadako said. “Most girls had to work for the state, become a clerk or a secretary.”

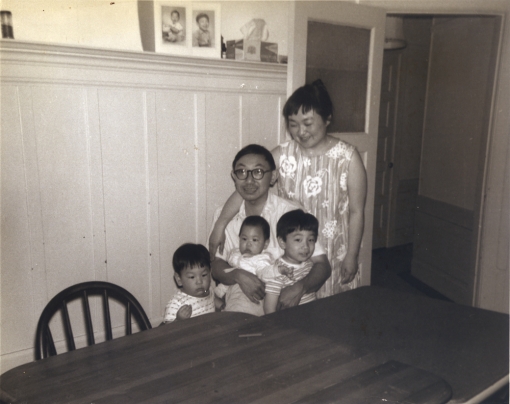

The Kashiwagis at home in San Francisco in 1965. Courtesy of the Kashiwagis.

The Kashiwagis at home in San Francisco in 1965. Courtesy of the Kashiwagis.

They were both open about sharing their internment experiences with their children. While they know others who have been too traumatized to speak about it, Sadako and Hiroshi felt that their history had to be shared.

In 1981, Hiroshi testified in San Francisco before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. The government issued a formal apology to Japanese Americans and redress payments in 1988.

Now, Hiroshi and Sadako are retired in San Francisco. Hiroshi writes poetry and books, many of which reference his personal struggles with internment. He meets with groups to talk about his life and spread awareness of that dark time in American history.

This summer, he and Sadako flew to Washington, DC, as part of a congregation of poets and writers to meet President Obama.

“It was awesome,” Hiroshi said. “We’ve never been to Washington, DC, before. We shook [Obama’s] hand and the first lady’s hand. The whole experience wasn’t something we had ever dreamed of.”

Sadako and Hiroshi fully appreciate how far they have come together. When Sadako learned she and Hiroshi would be photographed for this issue of Hyphen, she knew exactly what to wear to the shoot.

“This sweater symbolizes survival,” she said.

Kevin Lee is Hyphen’s journalism fellow. Nina Kahori Fallenbaum contributed to the research and reporting of this story.

Correction: Sadako Kashiwagi’s father did not “refuse to volunteer” for the US Army; as a foreign national, he could not serve in the US Army. He discouraged American-born Nisei to enlist, which led to his additional incarceration. Furthermore, Sadako Kashiwagi was never a school librarian nor did cleaning in public schools; she was a children’s librarian at San Francisco Public Library.

Comments