Sometimes when Kathleen Dang is at home by herself, she hears a strange and eerily disturbing sound — silence.

“When there’s so few people at home, it’s really weird,” she says, laughing. “I feel creeped out because there’s no one else with me.”

The Dang household, in the San Diego suburb of Clairemont, normally hums with the activity of seven people spanning three generations, ages 13 to 86. It’s one of a rising number of multigenerational households in the United States, and although they may struggle at times with lack of space and privacy, they still manage to make it work.

“When my friends come over, they’re like, ‘Wow, there’s so many people here. How do you handle it?’” says Kathleen, a 21-year-old senior at University of California San Diego. “I’ve already accepted it. There’s not that much conflict. If my grandmas are being irritating, I just deal and put on a straight face and move on with the day instead of getting upset.”

The percentage of households in the United States containing three or more generations has nearly tripled over the past 30 years, from 2.4 percent in 1980 to 7 percent in 2009, according to Census Bureau reports. Asians and Hispanics are about twice as likely as whites to live in multigenerational households, according to a 2010 study by the Pew Hispanic Center.

While experts ascribe the rise to immigrant values emphasizing the family or the down-turned economy, for the Dangs it is more out of necessity. Kathleen remembers there always being extra family around, as many as 11 under one roof. Then for three of four years, it was just the five of her immediate family: her parents, her two older sisters and herself. But when her younger brother Vincent was born, her maternal grandmother moved in to take care of him. Her paternal grandmother moved in later, after a lonesome stint living with busy relatives in Sacramento, for the reassuring activity and companionship of a constantly full house.

The family is often creative about finding ways to have space in the one-story, five-bedroom, two-bathroom house. The garage is used as office space for Kathleen’s parents (mom Tiffany owns a travel company and dad Luong runs an electrical contracting service). Vincent sleeps in the rear living room and spends most of his time in the game room to make up for his lack of a proper bedroom. Kathleen often comes home very late from school and has the house to herself while everyone sleeps.

Though Kathleen says the situation feels very natural to her — as someone who was frequently looked after by relatives as a child — she acknowledges that she is the only person she knows who lives with both of her grandmothers, who get along so well they refer to each other as twins. Kathleen admits it is they, the grandmas, who keep the household running smoothly: “They spoil us rotten by cleaning all the time, cooking our dinner all the time, and always doting on us because we’re quote-unquote too busy.”

Kathleen hopes that people will see in these photos the positive aspects of their living situation. “Even though there’s a lot of people, we can manage, we can deal,” she says. “And we’re happy about all the family here.”

Go further inside the Dang's home with this online exclusive video, which includes more photos by the Dangs as well as excerpts from an interview with Kathleen Dang.

Kathleen Dang, 21, grimaces at “pickled loquats that Grandma Dang made me eat that were disgustingly sour” to help her quiet a cough, while Grandma Dang, 86, looks on. Photo by oldest daughter Hillary Quyen Dang, 34.

“We generally take off our shoes by the front door and place them by the fish tank or bring them into our own rooms,” says Kathleen who took this photo. “There isn't usually a second row of shoes. This is because I was cleaning my room for New Year’s and needed to take my shoes out.”

Grandma Dang and Grandma Luu (right) at the vegetarian table during a Lunar New Year meal. “Only Grandma Luu is a full-time vegetarian,” says Kathleen, who took this photo. “Grandma Dang is vegetarian on important lunar dates. She started seriously following the vegetarian lunar rules after Grandpa Dang passed away [in 2010].”

“The grandmas” took this photo of the meat-eating table from the vegetarian table.

A view of the “meat eater” table at Lunar New Year dinner by Hillary, with a glimpse of the vegetarian table (a spare table brought out for big family dinners) in the background.

Vincent, 13, eating banh mi, as shot by the grandmothers.

Hillary’s photo of Grandma Luu, 78, lighting incense for the Lunar New Year at a table set right outside the door on the driveway.

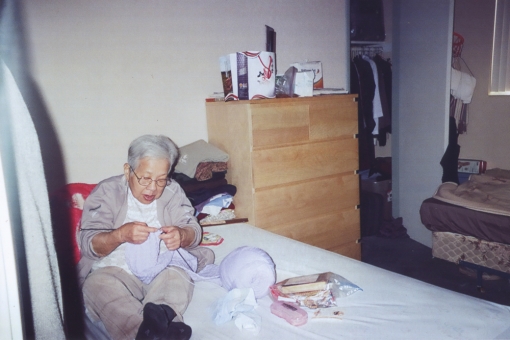

Grandma Luu’s photo of Grandma Dang in the bedroom they share. Kathleen calls Grandma Dang “a pro at knitting and crocheting.”

Kathleen’s photo of Grandma Dang sweeping the dining room and kitchen.

A photo by Luong of various gifts and candies from the Lunar New Year on the coffee table.

Hillary took this photo of their Uncle Hai picking from the lemon tree in the Dang’s backyard. “He does this every time he visits our house because of how well Grandma Luu tends the crops,” Kathleen says.

Vincent’s photo of mom Tiffany Dang, 56, watching Netflix at her desk in the parents’ office.

Kathleen’s photo of Aunt Kim chopping up duck in the backyard for a Lunar New Year meal.

A New Year's spread at the altar for Grandpa Dang, who passed away in 2010. Kathleen, who took this photo, calls his death “the most traumatic experience that we had. He was such a huge figure in our family. We all really miss him. It’s kind of like an open wound that he’s gone.” She notes that the family continues to honor him with flowers, incense every day and night, prayers, and traditional foods on his altar. “By doing all this for him, we feel better—we’re comforted.”

Lisa Wong Macabasco is Hyphen’s editor in chief. She last wrote about an online archive of the fashion histories of American women of color.

Comments