It’s hard to forget the images of terrifying walls of water rushing over buildings, carrying cars as if they were feathers; it’s hard to forget seeing miles of debris stretching out to the horizon. And yet just a few years after the disaster, survivors of Japan’s Great Earthquake and Tsunami were worried that they would be forgotten.

Now there is a remarkable teaching tool for young children to learn about the tsunami and how to help survivors. The children’s book Kamome: A Tsunami Boat Comes Home, written in Japanese and English by Amya Miller and Lori Dengler, is a helpful gateway and provides adults and children alike with lessons in kindness, resilience, and empathy. The book’s publication arrived just in time for the fifth anniversary of the disaster.

Kamome is the story of a tsunami boat which initially crossed the Pacific Ocean from Japan to the United States due to the ocean currents. During the Great Earthquake and Tsunami, the Japanese city of Rikuzentakata was hit by 42-foot-high tsunami waves. Rikuzentakata is in the Tohoku region, part of the country most affected by the tsunami. The city of Rikuzentakata alone lost many of its citizens during that time -- close to 1,700. Out of a forest of 70,000 pine trees, one tree survived, now called “the miracle pine.” Though many fishing boats in the town were destroyed, one of the fishing boats named “Kamome” (Japanese for seagull) survived and crossed the Pacific Ocean, floating upside down and growing foot-long barnacles inside.

Two years later, the boat Kamome washed up on the shores of Crescent City, California. It had the words “Takata High School” painted on its side. After some help determining its origin and owners, high school students from Crescent City decided to clean up the boat and return it to Rikuzentakata. Shortly after that, Kamome returned to its home via freighter, sparking cross-cultural friendships because of its extraordinary voyage. As a gesture of gratitude and goodwill, Japanese city officials invited a group of American high school students from Crescent City to visit Rikuzentakata. The American students visited Japan, learned about its culture and made friends with Japanese students. An exchange program began, and Japanese students visited Crescent City in turn. As of this writing, the exchange program continues; interested parties can follow the group’s Facebook and Flickr accounts for photos and developments. The most recent proceeds from the book will benefit the tours.

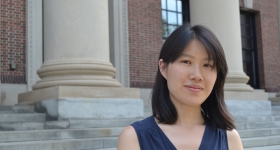

The book benefits from the experience of its authors, who have been deeply connected to the two cities. An American who spent the first 18 years of her life in Japan and is fluent in Japanese, co-author Amya Miller returned to Japan in 2011 to volunteer with relief efforts. She was eventually appointed Director of Global Public Relations by the mayor of Rikuzentakata. Co-author Lori Dengler is a Professor of Geology at Humboldt State University in California, not far from Crescent City. She was involved in inspecting the boat after it washed up, and had already been in contact with Rikuzentakata. The beautiful woodcut illustrations by Sansei artist Amy Uyeki are especially adept in their depiction of the power and beauty of ocean water and in their nuanced depiction of human emotions. Judging from the book’s website and resources, many of the illustrations are based on photographs of the actual places, as well as the boat itself.

Given the book’s young audience, it’s difficult to capture the emotional scope of the subject, or just what it means for one boat to return in the wake of so much destruction and loss of life. Parenting experts do not recommend showing scenes of massive destruction to young children, as the children may not separate what is happening in the book from their own lives. So this book is an age-appropriate one for teaching children about natural disasters, since it does not include such scenes. Instead, Uyeki’s stirring portraits of the ocean water carry the work of conveying destruction. Kamome also provides a a resource guide at the back of the book on talking to young children about disasters.

In order to create even greater emotional connection, the book could have recreated more scenes involving from the people involved in the boat’s recovery and return. As an avid reader and student of children’s books, I also wondered about the lack of a central character anchoring the book’s story arc. My 7-year-old daughter, for example, wanted to know more about what happened to the boat itself after its return; for her, the boat was a character, and she had a hard time relating to the high school students who emerged later on. My 10-year-old daughter had an easier time understanding the story, relating more to the friendships developed by the older students, and absorbing the book’s lessons of empathy. Overall, Kamome is a valuable resource for teaching children about natural disasters, human resilience, and the power of empathy to cross geographies and cultures.

Comments