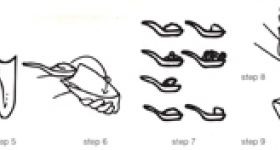

When the San Francisco Bay Area shelter-in-place order was announced to limit the spread of COVID-19, I decided to make dakjuk. Despite the grocery store already emptying out from panic buying, I was able to buy the last available whole chicken, the main ingredient for this Korean chicken rice porridge. For several hours, I boiled the precious chicken with leeks, onions and a few heads of garlic until the chicken fell apart. The broth creamy white, the kitchen fragrant with cooked garlic, I took the chicken out of the pot. The bones, or what was left of them, went into my compost bin. The meat, hand-shredded, back into the pot with some rice. I cooked the mixture for another hour, stirring continuously, seasoning with salt and pepper, until all the liquid had simmered off or was absorbed by the glutinous rice. I froze half of the finished porridge, set the rest in the fridge and ate it twice a day for the next 10 days.

The usual shelf-stable staples — dried beans, pasta, flour and rice — had already disappeared from grocery store shelves by this time and would be impossible to buy for several weeks. The ice cream aisle was almost empty, and chicken seemed to be the protein of choice for those who ate meat.

Earlier, I had tried to make a list before heading out to the store, wondering what I needed to buy. I had some experience in preparing for natural disasters where basic utilities and food sources may be cut for a while — earthquakes in the Bay Area, hurricanes in the Gulf Coast. I was more familiar with hurricane planning, having lived through a few major hurricanes during my six years living in the Gulf Coast. Hurricane planning revolves around having enough food and drinking water for a couple of days to a week and preparing for utility shut-downs — keeping a bathtub full of water, having a tank full of gas in the car, keeping the freezer door closed and buying a hand-cranked radio. Hurricanes that cause devastating, multi-week damages are still fairly rare but pandemics, rarer still. How long were we supposed to shop to prepare for a pandemic? Two weeks, two months or for the rest of the year? No one knew the answer.

My instincts told me to prepare my shelter-in-place pantry for the worst. For me, the idea of “the worst” stemmed from historical trauma passed down from my grandparents and parents. I searched my memories for survival stories from the Japanese occupation and the Korean War that followed shortly after, from the resulting famine and poverty from years of the land’s exploitation in their aftermath. My ancestors before them had passed down wisdom on how to survive boritgogae, the springtime famine period when the previous year’s food storage had all been eaten and the new year’s crop was not yet available. This was wisdom on how to stretch food and forage from the wild, how to create inventive new foods from what was available. Though my mind knew what I was experiencing was nothing close to what my ancestors had lived through during those times, my anxious body could not tell the difference. Registering these memories as my own, I grabbed whatever I could find — rice, dried goods and vegetables to ferment — my own survival food pantry that would also bring me comfort in the uncertain future ahead.

My instincts told me to prepare my shelter-in-place pantry for the worst. For me, the idea of “the worst” stemmed from historical trauma passed down from my grandparents and parents.

Dakjuk was one of the first dishes I gravitated towards, my ultimate comfort food. Chicken was always my favorite food growing up, and this highly laborious and nutritious food was how my mother showed her love for me. Though not strictly a survival food, it was a dish likely spurred by food scarcity, a way to feed many people for multiple meals with one small chicken. In a farming-based, largely mountainous terrain like Korea, eating meat of any kind, even chicken, was a rare event for most of the people’s 5,000 year history. The Korean phrase, “the egg-laying hen is butchered when the son-in-law visits,” describes the loving relationship between a mother-in-law and her daughter’s husband and implies that butchering a chicken to eat was a very big deal. Coincidentally, the ingredients for standard dakjuk are easily found in any grocery store in the United States, making it one of the more accessible Korean foods to make. It felt fitting at this time to search for foods that would not only bring me comfort, but could also stretch for multiple days or weeks, preparing for a day I may not be able to find a whole chicken.

Other meals I made were more inventive than traditional, making use of ingredients I was able to buy last minute. I bought a lot of frozen vegetables online as a backup plan in case I ran out of fresh produce. However, I quickly realized most frozen vegetables in the United States are packaged and prepared in a way that’s easily eaten by people accustomed to a Western diet but cannot easily be incorporated into Korean homestyle cooking. The frozen vegetables I bought advertised easy eating — Simply steam the package! — and included chopped food combinations that are rarely used in Korean cooking. What was I supposed to do with broccoli when no one eats broccoli regularly in Korea? What do I do with mushy, pre-steamed carrots when carrots in Korea are sauteed with oil and cooked al dente? At the same time, if my ancestors invented hearty soups with a distinctly Korean palette mixing ingredients like baked beans and Spam, I’d be able to figure something out with frozen broccoli and carrots. I decided to make a version of Korean vegetable steamed rice, usually made with dried turnip greens or bean sprouts. I ate it the traditional way, with a dipping sauce of soy sauce and sesame oil. It turned out delicious.

Much of what I know as Korean survival food was invented during the post-Korean War years as food from the U.S. Army entered into the Korean diet. One of the most well known food inventions of this time is budaejjigae or army base stew, a spicy hot soup using ingredients such as Spam, hot dogs, cheese and baked beans. Now a popularized snack food, this dish was once made from smuggled canned food items from the U.S. Army base and was a great source of meat for famished people.

More widespread at the time was the introduction of flour as a staple in the diet. Though rice has always been king in Korean food culture, so much so that a meal without rice is still considered a “snack,” it was also mostly unavailable after the war. Instead, the country experienced an abundance of flour as the United States supplied its surplus wheat flour to Korea. New food was invented using this relatively exotic ingredient. Wheat-based noodles and soojaebi, a wheat-dumpling soup, were eaten widely during this time. Though enjoyed by many younger Koreans today, they are synonymous with poverty and war to many Korean elders. Wheat probably still reminds them of war, famine and surviving without the comforts of familiar food passed down from our ancestors. These memories have traumatized an entire generation of Koreans. To this day, many Korean elders avoid eating noodle soup, 70 years after the Armistice Agreement temporarily ended the war.

How do I navigate the balance between survival and comfort food as I navigate between these two experiences, two lots of land, two ecosystems and two histories that are separate yet unified inside my body?

Ironically, flour is one item that is nearly impossible to source during this pandemic. If social media is to be believed, many Americans are baking bread in their homes right now. Given that “stress baking” was a popular term even before the pandemic, it’s unsurprising that baking is a source of comfort and relaxation for many anxious Americans right now. In contrast, my Korean American friends in Southern California tell me that flour is still fully stocked in Korean grocery stores near them; it doesn’t seem like many Koreans are seeking comfort in flour during this pandemic. Perhaps it’s still too soon. Perhaps we’ll eventually warm up to the thought of surviving off flour again after several months of sheltering in place, but not yet.

As Asian Americans, the ancestral food memories we’ve inherited for thousands of years do not necessarily mirror the land we live in. I feel this discrepancy even more so as a first-generation immigrant, still with strong familial ties to Korea. How do I navigate the balance between survival and comfort food as I navigate between these two experiences, two lots of land, two ecosystems and two histories that are separate yet unified inside my body?

In my last grocery shopping trip a few days ago, the scarcity mindset fraying my nerves, I finally decided to buy the most prized food item for many Koreans, the one thing that signified a family is financially doing okay — beef. Beef is associated with prosperity, comfort and longevity. I decided to buy beef because I realized I was in fact in a pandemic and not a war. I still have water and electricity at home; food will be back in grocery stores in a matter of weeks, not years. One day, we will be okay. I’m fortunate to be able to buy beef.

When I got home, I immediately portioned and placed the beef in the freezer, lovingly storing it for safekeeping. Even though I have no plans to eat this beef any time soon, the thought that it’s there and available for me seems to help me sleep through the night. And I’ve realized peace of mind may be the greatest gift I can give myself during this time, the thing that will help me survive — it’s what my ancestors would want.

Comments