IN 2003, IT’S MAINSTREAM — some might even say blasé — to be Asian American. But just a few decades ago, things were entirely different. “Asian Americans” did not exist. We were not a category that was included in the United States Census (we were considered “Other”); “Asian American” was not a term that was ever heard on TV or read in the newspaper. If you were of Asian descent prior to the laet 1960’s, you were, at best, “Oriental.” Back then, you had to choose to be Asian American.

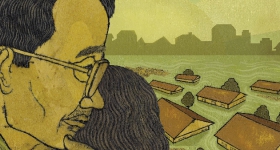

Around 1968 — a symbolic date for the beginning of the Asian American Movement — many of us decided to start calling ourselves “Asian American” because our worlds had been turned upside down. We had been deeply affected by the civil rights, black liberation, and anti-war struggles in the United States, as well as the struggles against colonialism and imperialism in Southeast Asia, China, Japan, Korea and the Philippines.

In that context, choosing to be Asian American was about deciding to be Asian and not white. It was about rejecting racial stratification and stereotypes of who Asian people were in the United States, and taking a stand on the side of oppressed peoples.

As the story goes, it was a grad student at UC Berkeley, Yuji Ichioka, who coined the term “Asian American.” This new identity arose out of our common experiences in America, the experience of being treated as if we were all the same and of an inferior race. As a result, the differences in our home countries became less important and we were able to find a common interest and identity with each other.

The term also broke with old ways of thinking, and symbolized a new way of looking at ourselves. The Black and Third World Liberation Movements, and people like Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael and Huey Newton inspired us — college students and young people — to question the way we were perceived (as the model minority), and later motivated us return to and address the problems within our own communities. At a time when the Black Panthers were on the rise, and there was palpable anger over the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, we were re-examining our identities as “Orientals.”

Asian American,” then, spoke to us because it was a refusal to allow white people and mainstream culture to define us. It gave us a rallying point that identified who we were and what we stood for during those times. It initially shocked some of the older folks — the Chinese Six Companies, the Japanese American Citizens League, our parents — but they, too, would come to understand that “Asian American” was to “Oriental” what “black” was to “Negro.”

building alliances

Looking back, it was the dynamic political climate of the ‘60s and ‘70s that allowed us to overcome the very real barriers of language or history in order to come together as Asian Americans, and to build alliances with other communities.

When I came to New York City from Hawaii for college, my experience was that it made little difference whether I was Chinese, Japanese, Filipino or Korean. We were all treated the same — badly. We were all subject to the same stereotypes, to the same racist attitudes and values. Yet, being treated this way actually pushed us together. And, importantly, being able to identify this as institutional racism helped us understand that it wasn’t because there was something inherently wrong with us as individuals.

This was an incredibly liberating experience.

Soon we were motivated to learn about our own cultures and family histories: the untold stories of Asians in America, the colonial history of Americans and Europeans in Asia. We felt anger at how our predecessors had been treated and how they suffered. We were amazed at their determination and achievements.

Instead of feeling ashamed of being Asian, we began to feel proud. In this sense, Asian pride was anti-racist and politically progressive. We began to feel as if we were all a part of one larger community, but it also brought us closer to Blacks, Puerto Ricans, Chicanos and Native Americans, groups I would not have ordinarily felt close to.

The injustices and racism exposed by the Vietnam War also helped cement a bond between different Asian groups living in America. In the eyes of the United States military, it didn’t matter if you were Vietnamese or Chinese, Cambodian or Laotian, you were a “gook,” and therefore sub-human. “The only good gook is a dead gook” was a popular saying. In fact, among people involved in the Asian American anti-war movement, there was a widespread belief that the Vietnam War was genocide similar to what had happened to Native Americans. And just as there have been hate crimes against Arabs and South Asians because of today’s “War on Terror,” Asians suffered similar injustices during the Vietnam War.

This political spirit also unified us with non-Asian communities. The efforts of African Americans, for example, were a great inspiration to us. Through their struggles, we began to see that people of color were asserting their own identities instead of trying to fit into a white world. Without the African American movements for civil rights and black liberation, we would not have been able to understand institutional racism as well; we would not have had an alternative direction

to follow.

When the African American community started asking questions about police brutality, lack of education, inadequate and unaffordable housing, and then, when they began acting on their new beliefs, we began wondering about ourselves and our own communities. Where were we in relationship to what was going on? Could we ignore what was going on around us and just keep on looking for Gum Shan? Would getting a “good education” to better ourselves be enough to build a new and different kind of society? It made many of us rethink our basic assumptions.

We had learned that Asians had been subject to racism and exclusion, to economic exploitation and second-class status, and that we had a history of resistance. And other groups had similar experiences. As we studied U.S. history from this perspective, we began to realize that it was the same system that was oppressing all of us, a system that regularly uses one group against the other to further and maintain their control and interests.

Consequently, there was a reason why we had a common interest with other people of color, with working class people of all ethnicities, and with women.

Born in this era of social change, “Asian American” was a radical political identity — not merely an ethnic label. Asian American consciousness manifested itself through vocal opposition and organizing against the Vietnam War, against racist hiring practices, against urban renewal projects. We fought for the development of affordable housing, accessible health care and self-determination in our communities. Soon, we became a movement, and gradually, more people began to use the term “Asian American.” It took about seven to eight years for most people in the community to adopt its usage. Eventually the term “Oriental” was no longer acceptable.

a new consciousness

With this new sense of identity came an Asian American consciousness that spread rapidly among high school and college students, and rippled into the community. By 1970, there were more than 70 campus and newly organized community groups with “Asian American” in their name. The term symbolized the new social and political attitudes that were sweeping through communities of color in the United States. It was also a clear break with the name “Oriental,” and it reflected the widespread belief among young Asian Americans that we — and no one else — should define who we are.

The more we examined our collective histories, the more we began to find a rich and complex past. And we became outraged at the depths of the economic, racial and gender exploitation that had forced our families into roles as subservient cooks, servants or coolies, garment workers and prostitutes, and which also improperly labeled us as the “model minority” comprised of “successful” businessmen, merchants or professionals. We rejected these representations. We discovered that we had fought against racism and struggled for unions at home, and supported democratic revolutions abroad. And certainly, not everyone agreed with our perspective. There were differences of opinion within the community between newer and older immigrants, between those with more money and those with less, and between those who wanted to assimilate and those who did not.

The strength of the Asian American movement, however, was undeniable. It was a radical sense of consciousness, representing a shift in our political awareness. It was a discovery of empowerment, and provided us with an understanding of our connection to other people’s struggles, both domestically and internationally.

But what does it mean to be “Asian American” in 2003? Has racism been eliminated? With America at war, is the internment of a people based upon race and ancestry a distant memory? Does being “Asian American” mean the same thing today as it did in the past?

No, it does not. Thirty years ago, being Asian American was about seeing ourselves in a different way, about creating a new vision of what life could be, and changing the status quo. It sometimes feels as if the term “Asian American” today has nothing to do with the revolutionary spirit that it grew out of — for some people, being Asian American is nothing more than a label next to a box you check every 10 years during the Census. Perhaps it is time to do away with the term “Asian American” so that we can, once again, decide for ourselves who we really are.

This essay is the result of a collaboration among Gordon Lee, and other activists and writers.

Comments