Diane C. Fujino’s biography on the iconic

Asian American activist Richard Aoki is revealing, fascinating, and at times

intensely moving. The book is a hefty 400 pages (100 pages of which are the often-enlightening

footnotes). A project that

began in 2003 at Aoki’s request, it took Fujino another nine years before the

book was published. Samurai Among

Panthers: Richard Aoki on Race, Resistance, and a Paradoxical Life switches in each chapter from Aoki’s own narration to

Fujino’s historical and sometimes psychological analyses. Fujino is a feminist

scholar who teaches in and chairs the Asian American studies department at the University

of California, Santa Barbara. She has written about Yuri Kochiyama and Fred Ho

and her research and writings focus on the Asian American movement, Japanese

and Asian American radicalism, and Afro-Asian solidarity. Fujino is currently working on two books, one about Japanese American radicalism and the other about the Asian American movements primarily of the 60s and 70s.

While Aoki was known as a private

person, he asked Fujino to record his life story. Aoki passed away in March

2009 before much of the book was written. Fujino says that she had shown him

drafted chapters, and that he was happy with what he saw. Toward the end of

his life, when he was going through serious health issues, he did not respond to

chapters that she sent him. “I think he would have been pleased with it,” Fujino said of the final product.

That doesn’t mean that everything always went smoothly.

Fujino struggled with the format of how to tell his story, on how to be true to

Aoki while still analyzing and critiquing some things he said. “Because he had

his views and I had my views,” Fujino said. “I’m an independent scholar. I

wanted to interpret some of what he said.” One example of something she could

not get him offer was a critique of the Black Panther Party, the

seminal black power group formed out of West Oakland by Merritt College

students Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale in 1966. Aoki was one of the first

members of the party and played key roles, including in its

formation -- Newton and Seale sought him as a

political intellect and later, for arms. Aoki used his experience in the

US Army to train and guide the nascent group. Aoki served as a field marshal and was the highest ranking,

non-black member of the organization. He was friend and political

ally to Newton and Seale. They knew each others’ families from the neighborhood

and were students at Merritt College together.

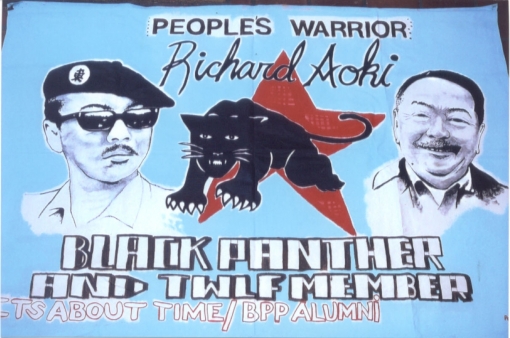

This banner, created for Richard Aoki's memorial service by Pete Bellencourt and commissioned by It's About Time/BPP Alumni, shows Aoki's most famous ties: with the Black Panther Party and Third World Liberation Front. He was also an important leader of the Asian American movement, represented by the small AAPA (Asian American Political Alliance) button on his beret. Photo courtesy of It's About Time.

When Fujino asked Aoki about sexism in the Black Panther Party, Aoki became upset. “He said, ‘Why are you asking that? People

always ask that, this is the first thing people ask about the Panthers,'" Fujino said. "From

my perspective, it was a really fair question to ask. I wasn’t a scribe for

him. I had a little different view. And I actually think it makes the book

stronger, rather than weaker. And I feel like I really honored his story.” The

book reads not as a rote homage to Aoki, but as a respectful

portrayal of him as a human being, rather than a hyper-masculine, one-dimensional political

icon.

The narrative sequences in the book are culled from hours of interview that Fujino conducted with Aoki in 2003-2004, supplemented with commentary. Aoki was three years old when his family was sent to the concentration camps during World War II at Topaz, UT. There, his parents separated. There, Aoki learned of racism. These and other events formed his opinion of race and resistance, as well as of family.

I'm beginning to get a little pissed regarding my early childhood, meaning that period from 1938 to 1942 when my family was intact, my community was intact, and I was growing up a happy little child, with the nickname of Chatterbox and doting grandparents. Then about a week after we left the camps, my mother's father died of a heart attack. He's the one who took me to the canteen and bought me little treats. I guess it all came down on him and he died. - excerpt from Aoki's narration in "Protecting the Japanese," Chapter 2.

Significant as the material deprivation was, other kinds of abandonments inflicted deeper psychological and political injuries on Richard. At a tender age, his faith in his parents' ability to protect him was shaken. He would have become aware of the unfairness in the world, of being different, and of being a member of a targeted people. Like the man in Children of the Camps, Richard lost faith in America and in the US government's professed committments to justice and equality. In short, he was deprived of even the illusion of the innocence of childhood. - excerpt from Fujino's analysis in the same chapter.

In many ways, Aoki’s family lived a very alternative and unaccepted lifestyle. After his parents split and the war

ended, Aoki and his younger brother, David, lived with their father and paternal

grandparents in West Oakland (where the paternal grandparents ran a noodle

factory). His mother lived in Berkeley. According to the text, Aoki only saw

his mother about a dozen times in the eight years after the war. Richard Aoki and his brother were also homeschooled by their father, Shozo Aoki. Richard himself was a

voracious reader, and said he read 600 library books a year when he was a

child. But according to primary documents such as family letters, Aoki’s

extended family did not approve of his father’s ways -- which included alcoholism

and illegal money making. His small non-nuclear family seemed ostracized

from the rest of his family at the time.

Even at the end of his life, it seemed that Aoki had a lot

of unanswered questions about his family. Fujino said that she doesn’t know why

Aoki went to live with his father instead of his mother after the war. No one seems to know. After eight years, his father split town without a word, and Aoki and his younger brother went to live

with his mother in Berkeley. During this time, Aoki became reacquainted with

his mother, a time that he said she calls the “happiest” period of her life. But it wasn’t

until later in life that he reconnected with extended family members, by

attending their memorials and befriending others, such as his cousin Jim Aoki, the family

historian. Aoki never married nor had children, though he had several

long-term relationships with women (his first girlfriend was his African

American neighbor). In some ways, he chose his political, activist life over

having a family, a choice over which he seemed to express regret later in life.

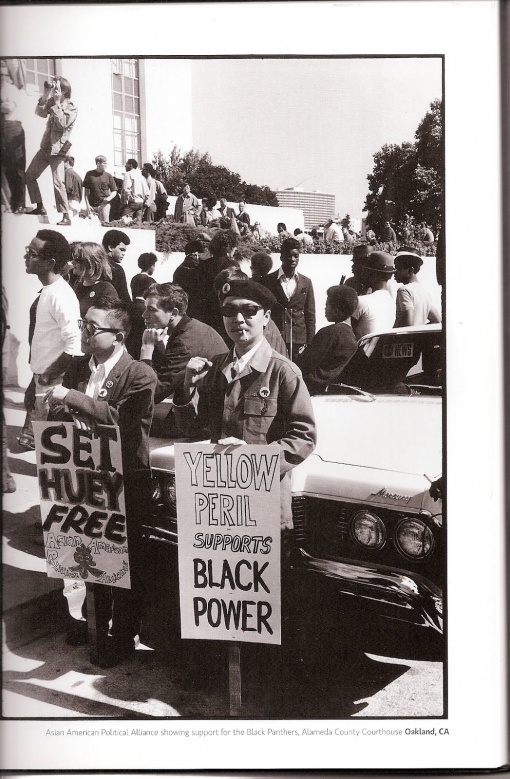

Richard Aoki holds a sign stating "Yellow Peril Supports Black Power" as a part of the Asian American Political Alliance's support for the Free Huey campaign, ca. 1968. Looking on at left is Richard's friend Douglas Daniels (in white T-shirt). Reprinted from Howard L. Bingham, Black Panthers 1968.

While the book is heavy, it reads very quickly. Aoki’s own words are

colorful, insightful and often delightful. Fujino's extensive research adds additional analysis, depth and nuance, to a figure she believes to be “one of the most important political leaders bridging the Asian American, Black Power, and Third World movements."

* * *

Full disclosure: The editor of Hyphen's Across the Desk series is a colleague of Diane Fujino at UC Santa Barbara's department of Asian American studies. However, views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Comments