For a while, it seemed like every issue of The New Yorker contained a story by Yiyun Li. I read each of these faithfully, eager to meet a new cast of characters and to see through their eyes the underside of Chinese life, past and present.

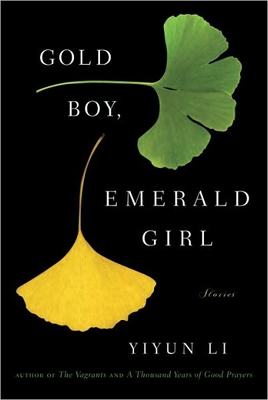

In the seven years since Yiyun’s debut short story won The Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize, she has published three books: the short story collection A Thousand Years of Good Prayers, the haunting novel The Vagrants, and her newest collection of short stories Gold Boy, Emerald Girl. And just this September, Yiyun, now an English professor at UC Davis, was granted the MacArthur “Genius Award,” a five-year fellowship of $500,000 recognizing her “creativity, originality, and potential to make important contributions in the future.” All this for a young woman writing, amazingly, in her second language.

Yiyun was generous enough to speak with Hyphen in November. I reached her at home in Oakland, our call memorably marked by poor cell phone reception, her young sons’ squabbles, and Yiyun’s quick, energetic laughter.

Congratulations on being named a 2010 MacArthur Fellow. When did you hear the news?

It was a big surprise. They called for a few days, but I did not pick up the phone calls because I didn’t recognize the number. In general I live as a hermit. [Laughter] In the end I won: they left a voicemail message.

I enjoyed your new book, Gold Boy, Emerald Girl. How do you see it in relation to your previous books, A Thousand Years of Good Prayers and The Vagrants, and why did you return to short stories?

I’ve always loved short stories. I love writing novels, too, but short stories are my favorite form. Most of the stories in this book were already written when The Vagrants came out. I’m very fond of the title story “Gold Boy, Emerald Girl,” which is a representative one. The title suggests a surface that’s not reliable; it’s about going beyond perfect beauty, past all the beautiful faces. I feel that I’ve matured a lot in this new book. I feel much more certain about what kind of stories I want to tell and how to tell them.

Throughout your work, there’s a focus on characters drawn from disenfranchised groups, like the poor, mentally ill, and disabled, or those who are lonely, alienated, or feel discarded in some way. How do these characters come to you?

As a solitary person, I’m naturally drawn to characters on the edge, characters who experience human tragedies, not dramatic, but small tragedies. If you look at the world, there are people with loud voices who grab attention wherever they go. Then there are people who are quiet and don’t want attention, or want attention but don’t get it, and I’m just interested in these people.

Your work also brings out issues affecting women and Chinese women in particular, such as the duties imposed by patriarchy, raising children or the inability to have children, and the benefits or pitfalls of beauty. What do your women characters teach us about this part of the human experience, and are there particular characters that fascinate you?

When I write, I tend to forget whether the characters are men or women, because I write from the inside and forget their gender, I forget they’re Chinese or speaking in Chinese. But of course they have their specific sensitivities. I just get into the characters and live through them and their wisdom. I’m very fond of the narrator in “Kindness” [the novella in Gold Boy, Emerald Girl], who’s again a very solitary character, a very stubborn woman. Her name is Moyan, which means “do not speak, do not talk.”

Many of your stories have political content and critically examine different aspects of Chinese society and history. Do you know if and how your work has been received in China?

I don’t think my books are very positively received in China. The books are not translated, not directly, but I know there are stories published in Chinese magazines or on the Internet. My books deal with things that are not positive or on the bright side of Chinese life, which is very hard for my own people to live with. There’s not anything I can do about that. When I write about America, it’ll be the dark and lonely side of America, too.

Your path in America is well known by now -- that you came to Iowa to study science but ended up in two writing programs -- but how exactly did this happen?

I got into non-fiction first because I needed a student visa. It was all circumstance. I’d never written anything before and fell in love with story writing and also writing in English. My parents weren’t happy when I first gave up science, but my husband has always been very supportive. He is the one who first said “give up science and do what you love.”

You recently did a reading at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in Manhattan. Does the term “Asian American” apply to you now that you’ve been in the US writing in English for many years?

I don’t even have an American passport, but I’m American in a way. I always say I want to be called an “international writer,” but in reality I think I’m Asian American.

What are your current projects and your plans for the MacArthur’s five-year fellowship period?

I don’t know yet. I’m working on a novel and a children’s book project, which really keep me focused. I hope the fellowship will allow me to negotiate less teaching time. This is my third year at UC Davis, and while I enjoy teaching, I always feel very ambivalent about it. My natural mode is not to have any authority over anyone, and that’s the part of teaching that I try to avoid.

And you’re also involved with the magazine A Public Space?

Yes, Brigid Hughes, who had been at Paris Review when it published “Immortality,” my first story, started this magazine and invited me to join. As a writer I don’t communicate with my contemporaries much -- most of my communications are with the dead, like Montaigne, whom I read every day -- and the magazine is a way of contributing to present dialogues. I believe that as one’s career advances, one has more responsibility to help other writers.

Comments