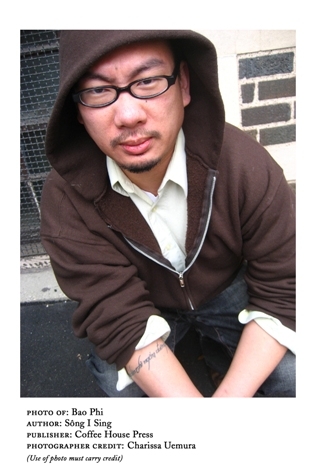

There is a certain catalyzing style

that comes of utter fearlessness, and the poet Bao Phi has cornered it with his

debut poetry collection, Sông I Sing.

Phi culls his lyric stories from news headlines and from the

street, calling attention to the injustices that make it into the papers, and

to those that don't. He reopens wounds caused by racism and its equally lethal

counterpart, complacency, and then examines them with a touch that is as robust

as it is reflective. The poems in Sông I

Sing unite beauty of phrase with intent of message, and the intimate

exchange between the two is stirring. That Phi is an accomplished spoken word

artist makes this feat no less impressive.

He is fiery and tender by turns. In “Dear Senator McCain,”

he berates John McCain for his blanket comment, “I hate the gooks” (“Senator /

what's the difference / between an Asian / and a gook / to you”), while "Nguyễn in the Promised Land" is more pensive in tone, a

superb document of the American dream and the shopkeeper who pursues it. An

immigrant everywoman who sends her daughter to college on “the dimes spun in

this store” and sells her customers lottery tickets “fat with long promises /

just beneath her reach,” she is a reminder of how honorable but also how cruel

that dream can be.

Repeating the words of racial antagonism -- “They called us

gook, chink, blanket ass, spic, nigger, coon -- / (and what was really sad is,

we called each other that, too)” -- Phi ensures that the effects of these slurs

don't calcify, foregoing any soothing treatment of them in order to keep the

cuts and bruises fresh. There's no room for slippery excuses, either: the “we

didn't mean it” contingent faces his scorn in equal proportion in “No Offense,”

where the reiteration of the titular phrase becomes the limp mantra for those

who do harm even as they say they intend none.

Photo of the author by Charissa Uemura

Phi's words are tempered in a fire that turns them

sharp-edged, adamantine, and as they ping around your head, they will seem

harsh and accusatory at times. In turning these pages, you may even stop and

think, how much doggedness is enough? But readers should press onward

and allow the ferociousness of Phi's poetry to do its work. In the

manifesto-like “Yellowbrown Babies for the Revolution,” Phi writes of having to

“make our own music / because none of these songs have ever been for us,” and

it's clear that in some sense he is speaking of himself -- of the language and

rhythm and energy that he generates from his material, for his people. “This is

to know what it is like,” he continues, with the weary gravity of the seasoned

leader, “to have to fight / to love ourselves.” It's a charge from poet to

listening audience (because these poems come alive when read aloud) to reject

any complicity in the cover-up that this is not a battlefield.

It may seem trite to call a poet a warrior. It may edge too

close to that over-used adage, “The pen is mightier than the sword.” But in the

case of Bao Phi, with his wrestling words and his implacable convictions, this

appellation would be true.

Jane Y. Kim is a journalist and fiction writer who lives in

Brooklyn. She works at Kaya Press.

Comments