For poet Victoria Chang, writing is risk-taking. "To be a creative person, you have to take risks all the time," she says during our phone interview. "Everything that you do and every word that you write has to be a risk. You have to not be afraid. You have to keep reinventing your writing."

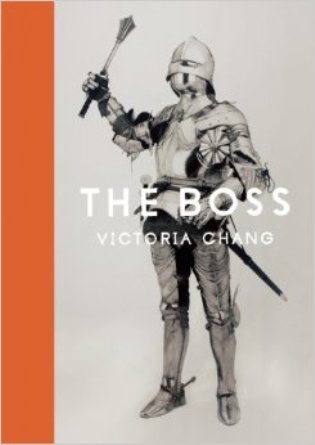

Chang certainly practices what she preaches, as her third poetry collection, The Boss (2013), presents her most innovative writing yet. Unlike prior works Circle (2005) and Salvinia Molesta (2008) where she tackles a broad range of topics, her most recent collection narrows its focus down to a central speaker coping with the intense pressures of family and corporate responsibilities.

Amid a larger backdrop of world tragedies and natural disasters, the book's speaker struggles to meet her daily duties of motherhood and professional life while also taking care of a father who has fallen victim to stroke-induced aphasia. The poems -- a mix of biographical narrative, meditations, and ekphrasis (through ruminations upon Edward Hopper paintings) -- are driven by heavy language-play and together interrogate notions of power and control.

"Watching my dad go through losing language made me realize how strange and transformative language is -- how close in meaning words can be but how meanings can change so much through small splits of the tongue," says Chang. "Listening to my dad try hard to talk each day and figuring things out through the context of his sentences made me think about the slippage of language and how it twists and turns and changes and morphs and changes again."

Chang's experimentation makes use of simple vocabulary for straightforward delivery of facts but allows the language to roam so that phrasal and associative repetitions make way for wild accretion of tension and meaning. On one level, the language parodies corporate jargon, as it does in "We Are High Performers":

We are high performers not normal but high performers

we perform things make papers smell like

perfume we are highly creative unusually industrious

exceptionally conscientious diligent intelligent

However, at its most virtuosic and sustained, Chang's play on language takes itself mirrors the often ironic content of the poems by doubling or even multiplying in suggestion. In the opening of "The Boss Rises" below, the stark contrast between simple sing-songy language and the ominous content parallels the growing divide between the boss and the workers:

The boss rises up the boss keeps her job

the boss is safe the workers are not

the boss smiles the boss files the boss

throws pennies at the workers

In "Edward Hopper's Office at Night," the repetitious word play enacts an obsessive mind crumbling upon itself in worry:

who will take care of my children later who will take care

of my father the will will take care

of no one a piece of paper cannot take care of anyone I

cannot take care of everyone on some nights

I wake in a panic and can't tell if I am dead or alive

Chang's life experiences led to the discovery of how much language functions as a means of achieving agency and hierarchy. "[T]he corporate world, parenting and my dad's loss of language -- I just feel like all of those things somehow intermixed together [...] some seconds of the day I felt like I'm on top of the world and another second I'm like 'I'm just a piece of shit,'" says Chang. "You're constantly negotiating even with yourself about how to be yourself. What I was really exploring without realizing it at the time is hierarchy and constant change and it just manifested through language shifting all the time."

Chang wrote the entire manuscript for The Boss in two months, mostly while waiting in a car until her four year-old daughter finished Chinese language class. Ironically, the capacity to produce a collection that questions the nature of power and control required a method where she let loose control of the language. "I feel like when you're writing a poem sometimes you try to control it so much," she says. "For this book I wanted to be the person being pulled by a really big dog that just freely goes wherever it wants to go and the dog is language. I wanted language to propel the poems."

The Boss recently made history as the first book ever by an Asian American author to be awarded a California Book Award (Silver Medal) since its inception in 1931.The award is given by the Commonwealth Club of California, the oldest educational non-profit organization in the country, to works of fiction, nonfiction and poetry of "exceptional literary merit."

"I don't expect to win anything so when I received the call I was so grateful," says Chang about the award. "It's like, wow, how did an immigrant kid who's so removed from the system win [...] [A]nd all the California Book Award finalists are great writers, so the award does have particular value for me."

The Boss also won the prestigious 2014 PEN Center USA Literary Award for poetry. “It's so cool to be able to represent,” says Chang. “I get to go to a fancy awards ceremony at the Beverly Hills Hotel, which I am sort of dreading and excited to go to at the same time.”

"Poet" was at first an unlikely vocation for Chang who was born in Detroit, MI to Taiwanese immigrants. She studied Asian Studies at the University of Michigan and Harvard and received her MBA from Stanford before she began her MFA studies. Chang was already working in prestigious investment banking and management consulting jobs before curiosity led her to get back into poetry by taking a poetry workshop at Stanford's Continuing Studies Program. Little did she know that the classes would be taught by talented Stegner fellows such as Rick Barot who sent her to take more classes with C. Dale Young who was editor at the time at The New England Review. Soon after, Chang applied for an MFA degree at Warren Wilson and was accepted on a full scholarship through the program’s Holden Minority Fellowship.

Today, Chang balances a professional life in marketing and communications with her writing life, along with raising a family of two young kids aged 8 and 6. When asked about the secret to her success, Chang says: "I don't actually feel like I'm that literary. But I'm the kind of person who is honestly interested in everything -- I'm always reading a lot of new things, I'm very curious about people, anything piques my interest [...] I always aim to be at the forefront looking over the edge and this is how I want my poetry to be -- I don't necessarily think that I always succeed but I think that definitely I try to not bore myself."

Comments