For December, we bring you an excerpt from Sujata Massey's forthcoming novel, The Widows of Malabar Hill. Inspired in part by the woman who made history as India’s first female attorney, The Widows of Malabar Hill is part historical novel set in 1920s Bombay, part detective novel. Perveen, the ambitious female protagonist, has been taxed with executing the will of a wealthy Muslim mill owner, when she notices that his three secluded widows have oddly signed their inheritances over to charity in the wake of his death. These early chapters paint a vivid picture of Perveen's struggles to make it as an attorney in a male-dominated field. — Karissa Chen, Senior Literature Editor

Chapter 3

The Spirit of Ecstasy

Bombay, February 1921

Around 3 o’clock, Mustafa burst into the upstairs office. “The SS London has arrived! I saw through the spectacles from our roof over to Ballard Pier.”

“Splendid!” Perveen clapped. Alice was just the remedy she needed for her dark mood.

A gust of air blew through the window, ruffling the Farid documents. As Perveen collected them, she thought about the cold, damp winds that had continuously buffeted her and Alice as they trudged from St. Hilda’s College to their various lectures. How they had talked and laughed — and shared secrets. This could be her life again, if she chose to open herself to Alice.

Their relationship had started with Perveen serving as Alice’s confessor. The Englishwoman’s revelation that she’d been expelled at 16 from Cheltenham Ladies’ College for having a girl in her bed had confounded Perveen. It was natural for female relatives and friends to sleep close together. But after Alice explained the longing she still felt for a long-ago classmate, Perveen understood how multifaceted relationships could be.

At St. Hilda’s, Alice buried herself in her mathematical studies to push away the loss of her true love. Outside of Perveen, nobody knew her truth — just as Alice was the only one who eventually heard the story of Perveen’s own past.

Now she wondered how much Alice had said about their college friendship to her parents. The Hobson-Joneses might be suspicious about any of Alice’s female friends, given her past troubles. Perveen decided to be on her best behavior.

Ballard Pier was a 20 minute walk away, but she didn’t want to arrive sweaty or with squashed sweets. It was easier to get a lift in Ramchandra’s spotlessly maintained rickshaw with its protective sunbonnet.

Ramchandra cycled easily through the streets and out to Ballard Pier, where she could see the impressive bulk of a white Pacific & Oriental steamship rising up behind the high stone walls.

Stepping down from the rickshaw, she paid Ramchandra, who immediately headed toward a beckoning sailor. She unpacked a sign she’d made on the back of an empty folder that said miss alice hobson-jones. Holding up a sign for a newcomer put her in the company of hundreds of male chauffeurs who’d come to meet the ship, but what else could she do?

As she craned her neck, looking for Alice, an Englishman’s voice cut into her ear. “Excuse me. Are you Miss Perveen Mistry?”

“Yes, I am.” She turned expectantly toward the red-haired gentleman.

“I’m Mr. Martin, secretary to Sir David Hobson-Jones. He and the others are waiting.”

Perveen caught a hint of reprimand in the last statement. “Mr. Martin, do you mean that everyone is still waiting for Alice to be ferried in?”

“Miss Hobson-Jones disembarked 20 minutes ago. Her trunks are loaded, and she’s already in the car, so come along smartly.”

Who did he think he was — a class prefect? Perveen followed the pompous aide through the crowd and to the curb, where he stopped before a long, sparkling silver vehicle.

Perveen gasped outright. “Is that a Silver Ghost?”

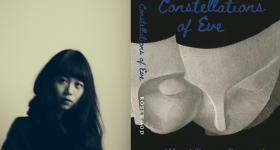

She knew for certain it was a Rolls. The shining car’s bonnet was topped with an elegantly sculpted silver ornament: a young woman leaning forward as if ready to dive into life, her arms outstretched like wings.

“Yes indeed,” Martin said. “It was a gift to the governor from the king of a nearby princely state.”

“What a present!” Privately, she wondered what kind of favor the monarch expected in exchange. Or was the gift merely a show of wealth?

“Perveen! You’re really here — I hoped you would come.” Alice squeezed out of the car’s back seat. Within moments, Perveen and her tissue-silk sari were crushed against Alice’s warm, peppermint-smelling mass.

Wrapping her arms around Alice’s comfortable bulk, Perveen said, “Sorry to have made you wait. I must apologize to your family for having delayed you.”

“Stuff and nonsense! I’ve been off the ship just long enough for Mummy to get her talons into me. You won’t believe — ”

“What won’t I believe?” A very blond woman who looked barely older than Alice was regarding them from the open-topped touring car. She was sweetly pretty in a lilac-colored frock and a matching cloche trimmed with white silk roses. Perveen looked for a trace of any part of this glamorous creature in Alice but couldn’t find anything past their shared hair color.

“Everything!” Alice answered.

From Alice’s sarcastic lilt, Perveen realized the mother-daughter relationship wasn’t an easy one. And what about Alice’s father? Perveen appraised the tall middle-aged gentleman wearing a beige linen lounge suit and a solar topi. Her friend had inherited his height.

As if they were schoolgirls, Alice took her by the hand. “Mummy and Dad, this is my dearest friend of all time, Perveen Mistry. And Perveen, may I introduce my mother, Lady Gwendolyn Hobson-Jones, and my father, Sir David Hobson-Jones?”

“We’ve heard all about your scrapes at Oxford with Alice!” Sir David said. He had a deeply textured tan that was typical of British who’d stayed a long time in India. When he smiled, his teeth were very white against his skin.

“So you are Perveen.” Gwendolyn Hobson-Jones pronounced it slowly, as if it were the name of an exotic place. “In your language, what does that name mean?”

“It means star in three languages: Persian, Arabic and Urdu. My grandfather chose my name.” As Perveen finished, she wondered if she’d said too much.

“Alice says you were the only girl studying law in your class at St. Hilda’s, which certainly makes you another kind of star.” Sir David delivered his attractive grin again.

“Not at all. Others came before me,” Perveen said. She was trying to get a read on whether he was being sincerely warm or patronizing.

“Perveen, have you any time to join us for a short ride to the house?” he asked. “We’re having a small tea to celebrate Alice’s arrival.”

Sir David’s invitation seemed to place him in the sincere camp. But as Perveen surveyed the car, she couldn’t figure out where she’d fit. The scowling Mr. Martin would likely sit next to the driver, and she didn’t see much room in the back, where Alice was rejoining her parents.

“That is very kind,” Perveen said. “If it’s really not an imposition … ”

“You must come!” Alice said.

“All right, then. If you tell me your address, I’ll hire a taxi to follow,” Perveen said, knowing that a climb up Malabar Hill would be too difficult for a rickshaw.

“Not a chance,” said Sir David. “You shall come along with us.”

“But Mr. Martin’s with us!” Lady Hobson-Jones objected.

Mr. Martin moved closer to Sir David, putting his back to Perveen. “I wished to explain to your daughter about the social life of young people — ”

“Another time,” Sir David said crisply. “You’ve got paperwork to deliver for me at the Secretariat. Miss Mistry shall ride with us.”

“Yes, Sir David,” he said. “Shall I call on Miss Hobson-Jones later this afternoon?”

“No. I’ll see you tomorrow in the office.” As the young man walked away despondently, Sir David gave Perveen and Alice each a wry look. “These young ICS men could use etiquette training.”

“I know just the school in Switzerland,” Alice joked.

“I hope you shan’t mind taking the seat next to the driver. With three of us in the back, it’s a bit cramped.” Lady Hobson-Jones was smiling rather nervously, as if she didn’t want to give the impression she felt uncomfortable sitting close to Perveen.

“It is no problem,” Perveen said with a smile. “I shall enjoy being close to the little silver lady.”

“The official name of the emblem is the Spirit of Ecstasy,” Sir David said. “She’s a splendid piece of design, just like the car itself.”

“My father’s car is right behind us — the Crossley piled up with my trunks. That’s why we’ve got Georgie’s Rolls.” The governor’s driver, a Sikh in a khaki uniform, kept a stone face, as if trying to ignore the indignity of both Alice’s words and Perveen’s proximity. But Perveen was determined to make the most of the special journey, so she waved at the crowd as they departed.

It was like being an actress. Perveen was a single Indian woman sitting up front in the governor’s car, an impossibility that would be discussed around many of Bombay’s cooking fires, verandahs and kitchen floors that evening.

“Where are we, exactly?” Alice asked as the harbor receded.

“Kennedy Sea-Face; but this stretch of curving road along the water is informally called the Queen’s Necklace because of the way it looks when the streetlights shine at night,” Perveen said, savoring her chance to play the Bombay expert. “Along the Chowpatty Beach side, you’ll see every sort of person coming out to eat the breeze, as one says in Hindi. On the right, many mansion blocks and hotels are going up. My brother’s just breaking ground on an apartment block to the right of that white building.”

“For whom does your brother work?” Sir David asked.

Perveen turned her head to speak directly to Alice’s father in the back seat. “Mistry Construction. My brother recently became executive officer.”

Sir David was still for a moment and then laughed. “Good God, I didn’t realize you were one of those Mistrys. Your family’s built modern Bombay! In fact, I’ve got a proposal from Lord Tata on my desk regarding development of Back Bay, with Mistry as the proposed contractor.”

“What a coincidence.” Perveen felt awkward. She’d only wanted Alice’s parents to know her brother wasn’t a lowly underling working for the British. But now they probably believed she was an Indian currying favor, to use the dreadful cliché.

Perveen returned her gaze to Kennedy Sea-Face. On the beach side, vendors were serving food and tea at dhabbas set up on the sand.

A young Parsi man with curly black hair was standing at one of these outdoor snack shops, talking to the small Hindu cook. The Parsi had a familiar lanky frame and a hooked nose. The Parsi wore an English suit and was leaning slightly on a cane.

Perveen put her hand to her mouth. It was Cyrus Sodawalla. Or, if it wasn’t, it looked exactly like the man she’d been trying to forget for the last four years.

Frantically, she reminded herself how many men in Bombay might have fair skin and curly black hair: thousands of Armenians, Anglo-Indians and Jews. And Cyrus didn’t use a cane.

The Silver Ghost was too fast. It sailed past the dhabba. Although Perveen craned her head, in seconds, the man had shrunk into a tiny black speck.

Perveen let out the breath she’d been holding. He was gone. And it was most fortunate that he hadn’t seen the car.

“What did we miss, Perveen?” Alice asked. “You look as if you’ve just seen a demon.”

Chapter 4

The Last Lesson

Bombay, August 1916

Running late and praying not to be noticed, Perveen hurried into the Government Law School. A cart had blocked the entrance to Bruce Street where her father needed to be dropped. The delay had caused Perveen to reach Elphinstone College just after nine — and she could only pray the professor hadn’t yet taken attendance.

Even though the surname Mistry fell in the middle of the alphabet, the lecturer had assigned Perveen a seat in the back row, ostensibly because she was a “special student” and not enrolled for a law degree. Today, she didn’t mind the placement because it made her arrival less noticeable. But after the first few seconds in her seat, she felt something cold and terrible seeping through her sari.

Not again!

The first time, someone had filled the groove in her wooden chair with water. On another occasion, her seat had been filled with black coffee; thankfully, she’d noticed and not sat down. This time, she’d sat down without looking first. She would not know what the fluid was until class was over and she’d reached the sanctuary of the college’s ladies’ lounge. This particular dampness was sticky. An ominous sign, as bad as the smirking faces of the students sitting nearby.

During the first term, Camellia Mistry had been shocked when Perveen complained to her about the students’ pranks. “You must tell the professors! It’s outrageous behavior.”

Perveen had explained the impossibility of this. “The lecturers don’t want me in class, so that won’t help. And if the boys learn I told on them, they’ll treat me worse.”

But life was worsening anyway. Two weeks ago, the results of examinations had been published in the Times of India, recognizing Perveen Mistry as the second-highest-scoring student among the first-year candidates for bachelors in law.

The Mistry family had celebrated, John baking her favorite lagan nu custard and Pappa breaking open three bottles of Perrier-Jouët. Neighbors had dropped in all afternoon and evening to share dessert and congratulations.

But her male classmates weren’t pleased.

The next time she handed an essay up the row of students to be collected by the proctor, the lecturer never received it and gave her a zero. Another afternoon, a gentleman purporting to be from the school administration left a telephone message at her home about a surprise cancellation of the next day’s law classes. Perveen was suspicious and went to check the classroom, reaching her seat just as tests were being handed out.

Today’s revenge was a sweet one, judging from the line of ants traveling up the chair. Barely able to absorb Professor Adakar’s words, Perveen stared straight ahead. In her mind, the words that he was writing on the board — something about one’s right to legal process — were being replaced by the hateful words a boy had hissed in her ear the first week:

Jubree joovak! You’ve no right to be here! You’re a pusree puroo who’ll ruin everything for our batch.

He’d called her a shrewish spoilsport. As if she were the one making life hell and not the wretched lot of them.

*

“Tamarind chutney,” Gulnaz said, wrinkling her nose at the silk sari she held 6 inches from her nose. “Those pigs must have taken it from their hostel dining room.”

“Are you sure it’s tamarind?” Perveen was standing in her blouse and petticoat in the college’s ladies’ lounge. This was the place where female students were supposed to retire between classes. At the moment, Gulnaz Banker and Hema Patel had her sari between them and were valiantly attacking the stains with soap and water taken from the adjacent lavatory.

Hema looked sympathetically at her. “We keep saying, why not read literature like we’re doing? We’ve got four girls together in one class. The men would never dare act against one without fearing all of would retaliate.”

“I can’t change my course of study. My father expects me to become the first female solicitor in Bombay.”

Gulnaz, who was a year ahead in school but had a rosebud prettiness and tiny size that made her seem younger, spoke up softly. “Perveen, you’re the impetuous type. Why not thrash it out with them? You must dream of banging them all over their stupid heads the way you did to Esther Vachha in school.”

“I was 8 years old, and she’d thrown sand on my lunch!” Perveen was annoyed that Gulnaz remembered this. “I’m more mature now. I keep my eyes on my notebook as much as I can, although that sometimes makes the professor think I’m not listening to him. Then the others laugh, and — oh, it’s awful.” Perveen felt an unbidden tear slide out.

“Poor girl!” Gulnaz sounded alarmed. “You mustn’t cry. Your sari’s almost as good as new. We’ll just hang it near the window to dry.”

Perveen reached out for her sari. “My class on Hindu law starts in 20 minutes. I can’t stay waiting for it to dry.”

“Mangoes will not ripen if you hurry them,” Hema said. “Sit down and take some deep breaths.”

Their caring was only making her feel panicked. “If I don’t go, I’ll miss the test.”

“Take it later,” Gulnaz advised. “Better not to shame yourself in public.”

Perveen took the sari out of their hands. “And what reason will I give the professor for my absence? A spot on my clothes? He’ll think I’m a typical silly girl!”

“But the spot is wet. People might think … ” Gulnaz’s voice dropped off. She was also a Parsi brought up with strict standards of hygiene.

“Silk will dry faster in the sun outside than inside this humid hellhole. And I’ve got an idea about how to wear it!” Perveen explained that if she draped her sari in the Hindu manner, with its pallu hanging over the back, the spot would be obscured. Aradhana, a Hindu girl studying at one of the lounge tables, hurried over to help.

Flanked by Gulnaz and Hema, Perveen went out into Elphinstone’s courtyard.

“Look!” Gulnaz pointed. “Esther Vachha is sitting with a man!”

Perveen followed her friend’s outraged stare to a wrought iron bench where her primary school nemesis was sitting and laughing. The young man with her was dressed like a Parsi and had thick black curls that tumbled perfectly over his forehead. Esther’s companion had an attractive profile with the kind of hooked nose that made Perveen think of portraits of ancient Persian royalty.

“He’s not a student here. Who could he be?” Hema asked excitedly.

Perveen had seen plenty of male students at the university, but none as handsome as this one. “I’ve never seen him before. But he certainly looks like a dandy.”

“I don’t care. I’d die for my children to have curls like that,” Gulnaz said.

“You are far too marriage minded!” Perveen scolded as Hema grabbed each of them by one hand and proceeded toward the bench.

“Hello, Esther,” Hema said. “Perveen was asking, who is your special friend?”

Esther smiled smugly. “Isn’t he lovely? He’s my cousin visiting from Calcutta. Mr. Cyrus Sodawalla.”

“Charmed,” the young man said, bowing slightly. He glanced over the three of them and then settled his eyes on Perveen. “Don’t introductions go both ways?”

“Miss Perveen Mistry is the first woman student at the Government Law School. Actually, she’s a third cousin,” Esther said with an artificial smile. “Miss Gulnaz Banker and Miss Hema Patel are both reading literature.”

“From your name, I’m guessing you’re a fizzy one,” Hema joked to the young man, making Perveen wince.

Cyrus Sodawalla smiled, displaying perfect white teeth. “When my grandfather came from Persia, his first job was selling bottled drinks. The British census required him to give a surname, and that’s what he got. Sodawalla — the soda-selling man.”

Perveen noted that his accent was different; it must have been the influence of Calcutta.

“That’s how my grandfather got his name,” Gulnaz cooed. “And now I’m saddled with the very boring surname of Banker.”

“Miss Mistry — are you also Parsi?” Cyrus asked, looking pointedly at the draping of Perveen’s sari. While the others all had their heads covered and a swag of fabric across their torsos that tucked gracefully into their saris’ waistlines, she did not.

Perveen was flustered. “Yes. I’m just wearing my sari another way.”

“Such a shame you lot are already 19 years old,” Esther teased. “Cyrus has come for bride choosing, and his family won’t look at a girl unless she’s younger than eighteen.”

“Is that because you’re also very young, Mr. Sodawalla?” Perveen’s question was sarcastic. Esther’s cousin had 5 o’clock shadow blooming on his cheeks and neck.

He gave Perveen a wounded look. “I’m 28 next month.”

“He-he! That’s old for a bridegroom,” Hema cut in. “I shan’t accept anyone older than 23.”

“The only reason I’ve held off is our family business. But it’s paid off. Soon the Sodawallas of Calcutta will be bottling all the whiskey in Bengal and Orissa. Actually, I’ve got a sample.” He patted a small lump in his jacket pocket.

Gulnaz gasped. “How naughty to be going about our college with a flask!”

Perveen wanted to laugh because Cyrus seemed so different from the pompous prigs in the law classes. Still, she didn’t want to be part of a fawning flock. So she smiled briefly and said, “I’ve no time for cocktails. Please enjoy your time in Bombay, and best of luck finding a wife.”

“To walk off just like that is rather rude!” Hema snapped once the three were on their way.

“I’ve got a test in Hindu Law,” Perveen said.

“But you’re walking away from the law classrooms,” Gulnaz pointed out. “Aren’t they on the far side?”

“Damnation — sorry! I must dash.” In her haste to get away from Cyrus and Esther, Perveen had passed the place she needed to go.

Stepping inside the building, she paused in the dimness and looked up the stairwell. Not a student was in sight, which meant she’d arrive late for a second time in the same day. Hurrying upstairs, she felt the edge of her sari slip off her shoulder and into the crook of her arm. As she draped the pallu back in place, she realized the folds around her hips were loose.

Just outside the classroom door, Perveen set down her heavy satchel to adjust her sari’s unfamiliar folds. What she really needed was to strip the whole thing off and start fresh, but she was too far from the ladies’ lounge. As she concentrated on pinching new pleats at her waist, she heard Mr. Joshi saying something about the test. Perveen gave up on her costume and opened the door, the creak of it causing a number of students to turn. All of them were from her earlier class. Raised eyebrows, smirks, snickers, and worst of all, the lecturer’s reprimand.

“How good of you to join us, Miss Mistry.” Mr. Joshi’s voice dripped sarcasm.

Perveen mumbled an apology and kept her gaze low as she hurried to her place. This was a different room than before, and her seat was clean. A mimeographed paper with six questions rested on the desk.

The young men around her were filling their fountain pens and starting in on the exam as Mr. Joshi came down the aisle to address her. “Coming in so late, I’m not sure you’re entitled to take this test.”

“Entitled” was a word that grated on her. Because she was Jamshedji Mistry’s daughter, she was supposedly entitled to read law — even though the law school wasn’t yet giving women degrees.

“Everyone’s working, and you are not. Did you neglect to bring a pen?” Without waiting for her answer, Mr. Joshi said, “I don’t suppose anyone’s got a spare pen?”

“There is no need, sir!” Perveen’s pen and some pencils were nestled in an embroidered silk pouch she carried inside her satchel. Reaching down, she hefted the heavy bag up onto the surface of her desk. Retrieving the pouch, she was surprised to find the pen missing. But the outside of her satchel showed a spreading black patch. Obviously, her pen had fallen out and was leaking. If she removed it, she’d just make a mess. And Mr. Joshi didn’t allow exams to be written in pencil.

As Mr. Joshi went back to the front of the room, Perveen sat in misery, staring at the paper she could not mark.

Forty minutes later, the paper was no longer blank. It was wet with a sprinkling of tears that had fallen fast and hard. As the students to her left began passing their completed tests toward the aisle, she didn’t bother putting it in the stack. She stayed in place, ignoring the irritated sounds of the men who had to brush past her to leave the classroom.

Finally, she was alone in the room. That was what she had been waiting for, because she didn’t want anyone watching her collect her things.

“What are you doing?” Mr. Joshi called out suddenly, startling her.

“Sorry?” She looked up, taken aback to see the lecturer hadn’t departed.

“You just put an examination in your bag — yes, I saw you do it.”

Perveen pulled out the damp, slightly crumpled paper. “Here it is. I had some trouble with my pen, so I couldn’t write anything.”

“But why did you put it in your bag?”

She answered honestly. “I was embarrassed to turn it in. The others would see.”

His eyes narrowed. “Stealing an examination is a violation of the honor code. I shall have to report it.”

Whispering from behind her informed her that the hall had not completely emptied.

“Sorry, but I was not intending to do anything with the test. As I said — ”

“If you were prepared to take an examination, you could have had a pen. You refused one.” Mr. Joshi’s voice rose. “What game are you playing today — or have you been playing games all along?”

Steadying herself, she said, “It’s not a game, sir. Just a mistake.”

The lecturer drew himself up; his face was flushed. “I said to the dean that allowing a female in the law school would be a mistake. I will repeat this truth when I write the notice of your honor code violation.”

Perveen’s whole body felt tight. “An honor code violation? I did nothing.”

“You intentionally stole a test that I’m sure you would have filled out at home — perhaps with your father’s help.”

Now she was furious. “I won’t answer to any charges that are unjustified.”

He cocked his head to one side and studied her with a cold smile. “It seems you believe your status is exalted enough to hold you above university law. Why is that, Miss Mistry?”

Rising to her feet, she spoke in a trembling voice,. “I’m not answering to any such charges, because I’ll have resigned.”

After the words had left her lips, she couldn’t believe it. What had she done? The proper behavior would have been to continue apologizing. But Mr. Joshi’s formidable expression had told her what was coming. He would have enlisted Mr. Adakar and the other law faculty to ensure she was convicted.

Mr. Joshi looked taken aback. After a moment, he said, “With resignation, there is also a formal process. But first there is my outstanding charge. My statement shall be used by the administration to consider whether to convene a hearing — ”

“Have you a brain, or is it sawdust?” The offensive slur flew out before she could stop herself. “I’ve quit!”

Going down the staircase, she felt as if she were afloat. What was the expression? Yes — a dying man clutches at sea foam. Like that man, she was moving in a soft, cool cloud that carried her away from the outraged, gesticulating Mr. Joshi. Although the sea foam was enough to bring her safety, she was still sure to drown.

Emerging from the building, Perveen headed for a dustbin. Discreetly pulling her handkerchief out of the edge of her blouse, she covered her hand with it and fished out of her satchel the leaking mother-of-pearl Parker pen her mother had given Perveen to celebrate her entrance into law school. It was useless. But then she hesitated. To throw it out would be to discard her mother’s generosity and hopes. She wrapped it doubly tight in the handkerchief and returned it to the bag.

“Miss Mistry, is that you?” a pleasant male voice inquired.

Startled, she turned around and saw that Esther’s cousin was lounging on the same bench as before near the fountain.

“Hello again.” Cyrus Sodawalla raised a hand in greeting. “Esther abandoned me in favor of Chaucer.”

Holding her satchel protectively against her drooping sari, Perveen nodded at him. “Kem cho.”

Switching to Gujarati, he said, “Sit down. You’ve the face of one who’s drunk cheap oil.”

Perveen realized that she did feel faint. She lowered herself onto the bench, being careful to leave several feet of space between them.

“I don’t need your whiskey,” she said in a warning tone.

Cyrus laughed shortly. “Esther already made it clear that was a poor joke. I’m sorry.”

Perveen’s faintess was slowly subsiding. “You’re forgiven.”

“You still look like death,” Cyrus said, his expression serious.

“I’ll be fine after a cup of tea.”

“You also need something to eat.” Brightening, he added, “Esther’s parents showed me a very good bakery a few streets from here. It’s called Yazdani’s.”

Perveen was impressed that this visitor to Bombay had heard of her favorite bakery-café in the city. But she also knew a decent young woman should not walk with a man unchaperoned. “There’s no reason for me to leave campus, Mr. Sodawalla. I can have a cup of tea in the ladies’ lounge.”

“But I can’t go inside there! And the truth is, I’ve missed a meal.”

The little-boy way his mouth turned down was endearing. And she’d rather leave the campus quickly after what had just happened. Didn’t the fact that her family knew the owner of Yazdani’s make going there a bit like having a chaperone? Slowly, she said, “That bakery is close to my family’s office. I could stop with you on my way there.”

Reprinted with permission of Soho Press.

Comments