Gen Z Speaks Out – A Conversation With YoungArts Artists

Hyphen sat down with four emerging Gen Z artists, Ameya Okamoto, Jeanie Chang, Jessica McCann and Kacey Kim, to talk about their approach to visual arts and the way it humanizes the Asian American experience during the current uptick in hate crimes. These emerging artists have won awards from the National YoungArts Foundation, a nonprofit founded in 1981 which identifies and supports young artists in the visual, literary and performing arts with creative and professional development opportunities.

Part of a generation coming of age in a time of increasingly visible class and economic disparity and racial violence heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic, these artists emphasize the role of creative expression as a way to come together in solidarity as well as cope with their own struggles.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

On Medium and Inspiration

Ameya Okamoto, 20, is a visual artist based in Massachusetts and is a U.S. Presidential Scholar in the Arts.

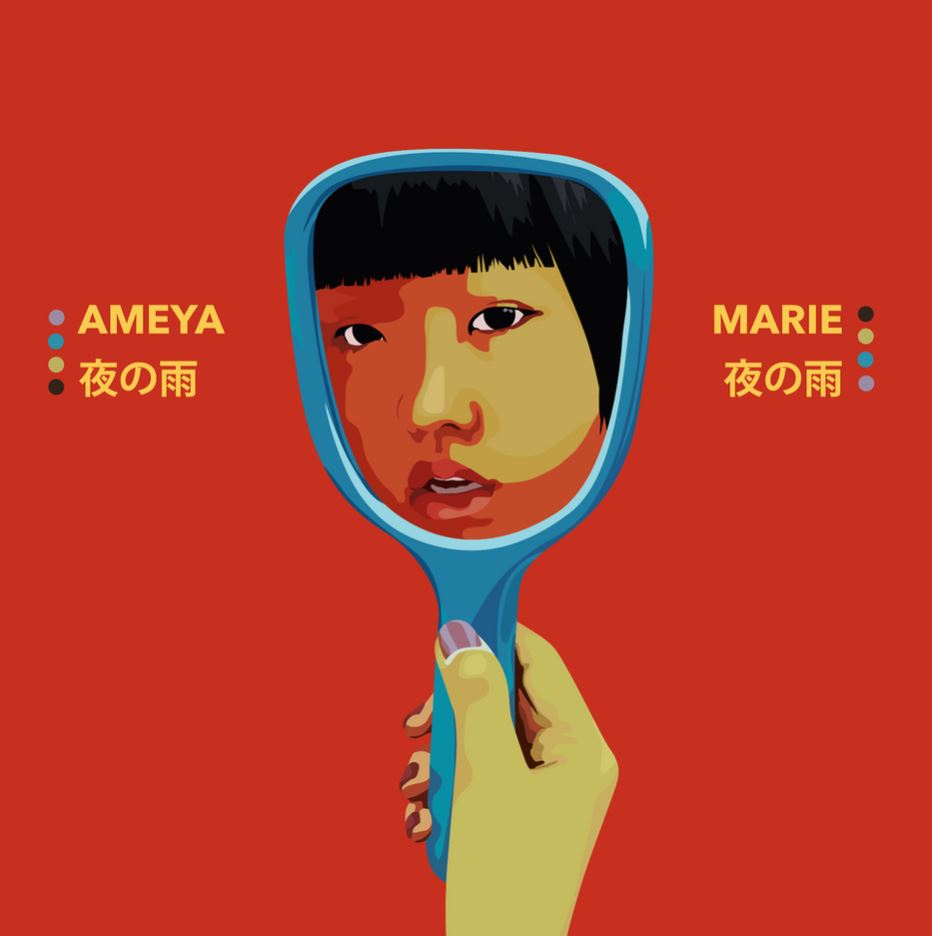

Ameya Marie. Image provided by Ameya Okamoto.

Okamoto: I discovered the computer as an endless outlet of creativity. Technology is something that a lot of artists avoid because there’s such an emphasis on using a traditional medium, but for a young person without a lot of resources to create, [technology] offers endless space and tools to create what I want.

Jessica McCann, 18, is a jeweler and maker of wearable art based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who works primarily in nickel sheet metal.

Consumption. Image provided by Jessica McCann.

Consumption. Image provided by Jessica McCann.

McCann: My school offers a wide array of art electives, and I chose jewelry. I immediately fell in love with metalsmithing and I started to work on it outside of school. At the beginning of the pandemic, since we’re just at home, I’ve created my own jeweler’s bench in my basement where I can work on my pieces and projects. Nature really inspired some of my pieces — I love butterflies, and they’re my favorite insect.

I gravitate towards metalsmithing instead of drawing or painting because I love how physical and hands-on I can be with metal. It’s basically therapy for me. I can work on my jewelry pieces for hours and hours straight without any breaks and feel like a few minutes have passed. It would be like being in a different world where there are no distractions and worries and it’s just me and no one else. That’s where I really try to work through my mental health because I didn’t know how to approach what I was experiencing, and when I found out I could do metalsmithing and I really enjoy what I’m doing, I realized I wasn’t so caught up in being frustrated and wasn’t so angry all the time.

Kacey Kim, 18, is an installation and performance artist based in Los Angeles, who describes her creations as a product of exploring her identity and Asian femininity.

Kung Flu. Image by Kacey Kim.

Kim: I form an idea of what I want my piece to be, using random thoughts or dreams that I quickly write down in my Notes app on my phone. I take the world around me and the social media that floods my phone and I listen to the opinions, feeling what they mean and translating them.

Jeanie Chang, 18, is based in Maryland, and uses the sewing machine as her primary tool.

I Am Both Detachable Denim. Image by Jeanie Chang.

I Am Both Detachable Denim. Image by Jeanie Chang.

Chang: I’ve been doing art since I was really young, but fashion design started this past March when I learned how to use a sewing machine because of quarantine. I learned from a video I must have watched 100 times.

On Art and Activism

Chang: I take inspiration from the Black community when looking at hip-hop culture in order to give representation to that community and bring compassion and connection to my art. I created designs for the NAACP Legal Defense this past summer for Black Lives Matter.

Okamoto: I do a lot of organizing as well as art. I’m attracted to visionary art because it is reactionary. I’m attracted to the speed. There are always events happening that require response, and with visual art and technology, it’s possible to bring together people around that, making awareness possible.

Even though I’m illustrating works of people who are not the same identities as me, I think that we all share the same desire to understand. I’d never understood the role of banners and posters until this summer, when I started seeing my banners and posters being used as shields against tear gas. It was a big learning moment for me — that art is not just validation of what we’re doing and organizing, and that it’s powerful to see it being used literally as shield.

Intersectional Supper. Image by Ameya Okamoto.

The most meaningful piece I’ve created is a 9-foot vinyl banner, a piece I created that is a collage of all the pieces I’ve made in collaboration with Black Lives Matter individuals and organizations. Protest, and the idea of protest and revolution and race — the idea of what is right and what to do from here, what our role is — are the leading questions in my artwork.

On Art and Identity

Chang: I see Korean and American as one whole identity instead of fragments of both. Culture’s different in Korean and American entertainment. In Korean culture, it’s structured — designers work alongside artists, and brands are connected within the industry. I like the idea of being connected through brand artists because I want to dabble in a lot of areas.

[Among Asians], collectivism, being in a group, is very common, while in America, people are focused on freedom. During COVID-19, we saw people doing things because of freedom that caused me to rethink a lot of my philosophies. Growing up, I thought I should have more of an American philosophy, but maybe there should be some type of limit. That’s caused me to rethink a lot of the mentality I had before and is kind of why I started this collection.

Jeogori Hoodie and Up-cycled Jeogori Sleeve-Glove. Image by Jeanie Chang.

The hoodie is a Western silhouette of American hip-hop culture and streetwear, but I combined the color philosophy and detail with the top part of the hanbok, the Korean garment. I cut up a lot of fabric scraps so that it represents putting things together into one thing, as a combination of a lot of things represents a lot of cultural things coming together.

Kim: By depicting Asian femininity, I rebel against set narratives and a portrayal of Asian women in Western popular culture that leaves no room for familial or self-love.

I also see myself as an activist who targets issues around the Korean community, such as racism and stereotypes that depict Asian America in an inaccurate way. It’s not spoken about much. [In America in 2020], I wanted to combine pictures that take on demeaning stereotypes of Asian Americans and a figure trapped in a yellow vinyl suitcase to reveal the xenophobia Asian Americans were struggling with that reached a peak this year. One of my family members was harassed at the beginning of COVID-19, and it was hard for me to comprehend how a family member is a piece of luggage carrying a virus, needing to be sent back to China because of ethnicity.

America in 2020. Image by Kacey Kim.

The YoungArts Impact

Okamoto: It provided me with validation and support and a community to always back me up, one of the most powerful things one can give to a young creative. All my best friends I’ve met through YoungArts.

McCann: I had previously no means of getting my art out there for others to see, and it gave me confidence in myself that I could be an international artist if I wanted to be in the future. YoungArts saw a potential in me which made me actually believe in myself and my potential. It gave me a voice and a stepping stone to an artistic career.

Chang: It’s so easy to compare yourself as an artist and my confidence was definitely limited. I was entering local competitions and schoolwide, and I wasn’t winning anything and thought maybe I shouldn’t do this as a career if I can’t even do it locally. But YoungArts looks at your potential and how you want to impact your world rather than just your technical abilities. They look at ideas and what you want to represent.

Kim: I learned that art is what you make of it, to be shared with the whole world rather than to gain approval from an audience. Share what you truly want to share and have your voice heard. As an artist sometimes I get lost in trying to create art that others will like. It’s important to take a step back and understand how the artist’s role is to share the stories and truth even if it’s not powerful to the rest of the audience.

Looking Forward

Okamoto: The world is so uncertain, and I’m dealing with a lot of uncertainty. The pandemic has definitely underlined the idea that we have no idea what’s coming. We can’t prepare for it and the only thing I can do right now is explore my values and the themes of art that really interest me.

McCann: I feel like Asian American teenagers in the past and still today go into math and sciences, whether it’s parents or societal pressure to be intellectual. In the future, I see Asian Americans going out to do more and explore more in other fields instead of just the sciences. There needs to be more outreach and exposure. As an artist you’re going to be skillful and talented and creative, and I feel like there’s not enough appreciation for the talent in art.

Restraint. Image provided by Jessica McCann

Chang: I think I’ll be working across a lot of disciplines, with the end goal of a creative director. There’s no straight path, but I’d love to work with anyone who does storytelling through the arts and to branch out and experiment with a lot of different mediums to tell a story.

Kim: Find the theme you want to focus on in your art. Speaking your truth is something really important. Trust the process, the trial and error, figuring out what you want this piece to talk about, what theme I want to talk about through my art. I hope to embrace the Asian identity and speak up about the aspects of Korean culture that I wasn’t able to celebrate when I was growing up.

Comments