Misguided teenage boy seeks big strong father-figure to make him a man, rescue damsel in distress, and rid town of terrorizing thugs. Sound familiar? Clint Eastwood's latest film Gran Torino reimagines this archetypal American story, replacing the genteel townsfolk with Hmong immigrants and instead of the Wild West we get the dusty ghost town of modern-day Detroit. This is the new, new frontier -- a place where cowboy bandits are replaced by caravans of Latino and Asian gangstas holding Uzis instead of six-shooters, and roving bands of rapacious Indians are replaced by loitering black youth threatening the maidenhood of virtuous young ladies. Only the whiskey drinking gun-slinger saving the day remains the same. No one can play Clint Eastwood quite like Clint Eastwood.

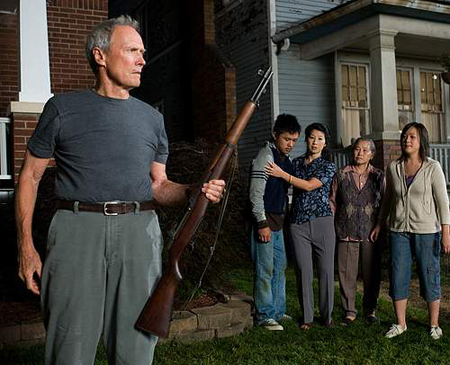

In this case, Eastwood is Walt Kowalski, a racist Polish American Korean War veteran annoyed by his new Hmong neighbors, his ungrateful progeny, and the neophyte local Catholic priest. Kowalski is content to sit on the porch and drink Natty Ice, but change has come for Kowalski and his lawn gnomes. Everyone wants a piece of Walt, mainly his classic muscle car, the eponymous Gran Torino, a stand-in for a passing era of Americana. His bratty granddaughter asks Kowalski to will it to her when he dies, whereas Kowalski’s young neighbor Thao (played by first time Hmong American actor Bee Vang) foregoes formality and attempts to steal the car as an initiation ritual into the local Hmong gang led by his cousin. Once Thao’s family discovers his foiled robbery attempt, he is placed in indentured servitude to Kowalski, the unwilling mentor.

What results is a perfectly tight film about generations learning from each other, and a racist old man’s reconciliation with the changing demographic of his town. Formulaic platitudes aside, this film does have something interesting to say about the changing face of America. The Gran Torino itself serves as a crux for this cross-generational movie. It is the vestige of an America that, like its owner, is past its prime but still holds a nostalgia evoking mystique felt even by those driving hybrids. The muscle car is the only gift of value the grizzled Kowalski has left to offer this changing world, and he must find a worthy new owner, one who can embody the immutable ideals of American manhood: stand up for the innocent, earn your keep, do it yourself, and know how to grill a steak. The politically correct twist that Kowalski must accept is that this all-American young man is the timid gook next door.

Gran Torino does pass the torch, although not quite in the dramatic fashion that some film critics will have you believe. It may be a newsflash to some that America is an ethnically diverse place, but the American myth of good versus evil and the powerful protecting the innocent is an apocryphal story almost as old as Eastwood. While its simplicity may be powerfully convincing, Gran Torino represents present-day America about as much as Eastwood’s spaghetti westerns that were filmed in Andalusia, Spain in the 1960s represent the Wild West of the post-Civil War America. In actuality, Gran Torino has more to teach about American story-telling than about America itself.

It’s only fitting that this is Eastwood’s last acting role. It’s an excellent bookend to a legendary acting career that has metamorphosed into America’s most consistently great directing talent. Eastwood the director usurps Eastwood the actor and the genre that made his career. While it may be offensive that each character in the film represents a hamstrung stereotype, the most parodied character is Dirty Harry himself. While the shotgun-wielding Kowalski threatening, “Get the hell off my lawn!” may sound just as menacing as “Go ahead, make my day,” it’s much funnier this time around. Even Eastwood’s son, Scott Reeves, gets in on the act by playing an ineffective wigga with more bark than bite, severely reprimanded by Kowalski for his foolishness and lack of gumption.

Eastwood the storyteller is the opposite of the cantankerous Kowalski; he is an aged and hilarious cynic, more Carlin than Clint. The film honors the American myth of the anti-hero, while subtly poking fun at the same time. Gran Torino surreptitiously reveals that Dirty Harry isn’t dead as much as he never truly existed, at least not the way we saw him. Eastwood’s embarrassingly grizzled voice singing the film’s theme song over the end credits is a comedic parting shot, reminding us that the gun-slinging hero of American mythos might just be a grumpy man that took himself a little too seriously.

Jason Coe, Hyphen's former film editor, is guest-blogging for Hyphen from Beijing.

Comments