Comics have come a long way. No longer just for kids and geeks, the genre has evolved from the realm of superhero fantasy to literature in its own right capable of exploring deeper personal and social issues (the New York Times now has a best-seller list for graphic novels).

At the forefront of the comics evolution are Gene Luen Yang and Derek Kirk Kim, creators of the short-story collection The Eternal Smile, which recently won the comic book industry’s most coveted Eisner Prize for best short story. The two, who met in 1995 at an alternative press convention in San Jose, California, each have a long string of accomplishments behind them. Yang is the first graphic novelist ever to be nominated for the National Book Award, for his book American Born Chinese (a definite must-read which has made its way into many academic reading lists). Kim won three of the most famous comic book awards (the Eisner, Harvey, and Ignatz) for his first collection Same Difference and Other Stories.

The Eternal Smile, written by Yang and illustrated by Kim, consists of three short stories that explore the different dimensions and roles that fantasy inhabits in our lives. The first story, “Duncan’s Kingdom,” is about teenage boy’s escape from his difficult family life by imagining himself as a knight who defeats the evil Frog King to win his princess’ hand in marriage. The second story, “Gran’pa Greenbax and The Eternal Smile,” is about a reality TV show featuring roboticized frogs whose money-grubbing leader co-opts a mysterious smile he finds in the sky to start his own corrupt religious following. The final story, “Urgent Request,” which won Yang and Kim their Eisner, features a meek office employee who falls victim to an email scam led by a Prince Henry Alembu of Nigeria.

Each story involves a passive character who finds solace, freedom, or salvation through fantasy worlds. The stories, created at different points in the authors’ lives, track their maturing attitudes toward fantasy. “I think I went from a sort of geek self-hate where I thought fantasy was just purely escapist to something more positive,” Yang explains.

Yang’s original view began to be transformed by a conversation he had with one of his high school students: “[The student] was really quiet in class … but it turned out that he was really involved in one of those online gaming environments, and in that he was a big deal … and when he talked about it this side of him came out that I’d never seen before … [H]e would run guilds and be in charge of all these other warriors who are played by folks who were 10 or 15 years older than him... [A]s he matured, he integrated more and more of that fantasy self of his into his everyday life, and I really think that if he hadn’t had that fantasy environment to experiment in and to practice I don’t know if he would have been able to integrate those leadership skills and that confidence so easily into his real life.”

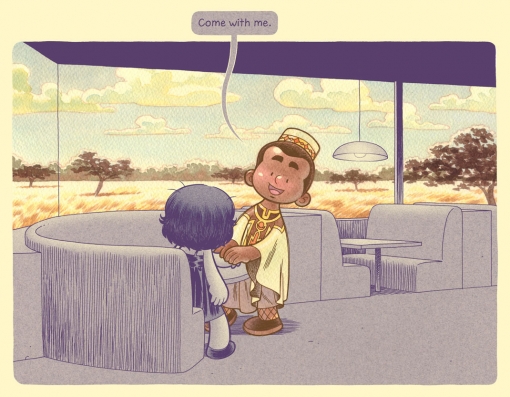

A similar development occurs in the award-winning story “Urgent Request.” Although the main character Janet Oh suspects all along that the email pleas for money to which she succumbs are scams, the email exchange between her and the fictitious Prince Alembu allows her to enter into a make-believe world where love and admiration come easily, in contrast to her actual life where she is routinely mocked and undervalued. Fantasy allows us to see our best selves, which is the first step toward the most positive heights of self-realization. It is a great credit to Yang’s deft storytelling abilities that such a profound lesson is conveyed through an economic use of words and visuals.

Kim’s illustrations brilliantly dramatize the story line in “Urgent Request,” as it does in the other two stories. His gift as a master artist is evident in the versatility he displays. Each story involves a drawing style so different that one could hardly guess they all came from the same hand. “Duncan’s Kingdom” displays a typical fantasy style of drawing akin to Marvel and DC comics. The drawings for “Gran’pa Greenbax and The Eternal Smile” display a style reminiscent of the Uncle Scrooge comics that both Yang and Kim enjoyed as kids. “Urgent Request” employs the appeal of indie comics -- Kim uses monochromatic colors to depict Janet’s dull world and surprises the reader with shots of full color for her fantasy scenes.

Brilliance, of course, comes with a lot of hard work. Kim spends 10-12 hours a day on average to create three panels at the most. “Comics takes such mental strength," says Kim. "When you can do it that pretty much braces you for any other kind of job. So anything that I do that’s not comics I think is going to be easy.”

Despite the huge amounts of labor and discipline required, Kim wouldn’t opt for any other artistic expression. “Basically, I just wanted to tell stories and if you want complete creative control, comics is the only way to go,” says Kim. Yang agrees: “Generally, all the work that you do is for somebody else’s story in animation, and comics is the only cartooning medium where you have control over your story from the outset.”

While Yang and Kim agree upon the advantages of comics, the two diverge on their forecast of the medium’s direction. Yang explains that since comics’ traditional strength of depicting the fantastical has been rivaled by technological advances in computer animation, the future direction of comics just might lead into more memoir-style formats along the lines of Maus or Persepolis: “[T]he strength in comics lies in its intimacy. I feel like comics are probably the most intimate visual media that we have. When you look at a comic you’re actually looking at lines and movement from somebody’s hand … when you see a person’s drawing styles you’re getting a sense of who that person is.”

In contrast, Kim questions whether comics will ever merge into the mainstream: “There’s too much of a leap in imagination that needs to happen for you to really get into comics and some people just don’t have that muscle in their brain,” Kim says. “So I think that [comics] will be much more popular than before but I don’t really ever see it being at the level of novels.”

Differences aside, they share the same ultimate objective, expressed by Yang: “My primary goal is to just tell a story that’s engaging enough so that a person will want to finish it. There’s a certain amount of work that’s there when you’re reading a comic, so I want that work to pay off for the reader.”

Yang’s upcoming projects include Four Angels, a book about a video-game obsessed med-school student, and Boxers and Saints, an historical fiction piece about the Boxer Rebellion. Among Kim’s next works is a series called Tune about an art school dropout who finds himself lost in a world without art.

Comments

Go Abi! What a splendid article on Gene Yang and Derek Kirk Kim. I've been waiting for more Hyphen coverage of the graphic novel, yipee!