Seems like more people are taking Tao Lin seriously. Or at least paying more attention. Since Hyphen featured him in a Spring 2007 article called “The Art of Depression,” the 27-year old writer has published three more books and continues to gain wider press coverage from the likes of the New York Times. He has been hailed as the “New Lit Boy” by New York Magazine and the “next big thing in urban hipster lit” by salon.com.

Lin’s insane publicity ploys have often been the culprit to his fame. Before his newly released novel Richard Yates was published, he famously auctioned six shares of his then unfinished novel on eBay for $2,000 each in exchange for 10 percent of the US profits. And people actually bought them. His other attention-getting stunts have included naming his short story characters (some of them hamsters) after magazine editors who rejected his submissions, holding raffles through his blog for various Lin paraphernalia prizes (such as used notebooks, page proofs, Tao Lin T-shirts, and drawings of hamsters), and most recently, linking his Twitter tweets to Autostraddle (an online lesbian magazine).

Richard Yates, the name of an actual novelist and a title which has nothing to do with the book (except for offhand title references to the novelist’s work), has been released to notably bifurcated reviews. Those who love it remark upon Lin’s self-awareness and ability to capture the internet generation’s malaise and loneliness. Those who hate it dismiss the book as juvenile, undergraduate drivel, and Lin as an annoying, shameless self-promoter.

The novel follows the love story of 22-year-old fledgling writer Haley Joel Osment and 16-year-old Dakota Fanning (actual names of child stars just as randomly selected as the title) as it springs from flirtatious Gmail chats, blossoms into disaffected hipster romance, disintegrates into suspicious accusations, circles back to flirtatious Gmail chats, and descends all the way to maniacal depths of bulimia and emotional-psychological manipulation. In between, they commute from New York to New Jersey, hoodwink Dakota Fanning’s hysterical mom, desultorily walk around Price Chopper, shoplift from American Apparel, and have disappointing lemon sex (read the book).

Lin’s sparse writing style narrates one event after another in a flat, detached tone without much authorial description, commentary, or insight. The following passage where Haley Joel Osment greets Dakota Fanning at the train terminal is about as emotional or profound as any passage gets in Richard Yates:

“I can’t comprehend how people can be late or obese,” said Haley Joel Osment.“If you are obese that means you have given up on life. And if you are late that means you like something else, not the person you were late to meet. It doesn’t mean that necessarily, but it means that to the other person, if the other person doesn’t block out that it happened. It’s hard to block out things like that when all I ever talk about is that all humans are assholes.”

Taking into account Lin’s relative versatility as a writer (perhaps best showcased in his hilarious parody of the Time article on Jonathan Franzen), it becomes clear that the novel’s detached writing style was determined by choice rather than by some ingrained quirk. But why Lin chooses to write in this way is perplexing given its tedious outcome. “I think I’ve had a number of styles, and I like each of them,” says Lin in his slow, monotone voice. “[F]or Richard Yates, I didn’t want to have passages where it was like me talking about how I felt about the story, and it had a lot of information to convey that would naturally be conveyed through dialogue and Gmail chat so I didn’t need to use my voice and say what was happening.”

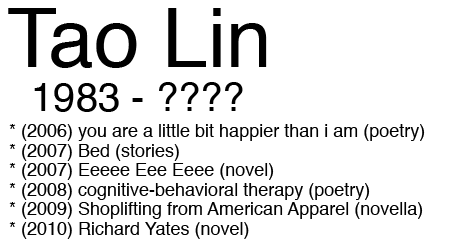

A bit more narratorial involvement, though, would have helped. The few funny bits in the novel, consisting mostly of Haley Joel Osment’s worried thoughts, failed to compensate for the unvarying tone and lack of suspense. The only way I was able to get through most of the novel was by reading in 15-minute spurts (and I still have yet to finish it, in fact). Strangely enough, I still found the book to be a worthwhile read if for no other reason than that I haven’t read anything like it before. Although you won't see me rushing to read the rest of Lin's work listed in this graphic from a Tao Lin T-shirt:

In person, Lin seems to have a lot in common with his apathetic, deadpan characters. Interviewing him was like pulling teeth, or trying to squeeze water from a rock. His answers consisted of many “I don’t knows” and “[T]hat word doesn’t mean anything to me,” as well as “I don’t get excited about anything.” The only time I sensed the faintest trace of animation in his demeanor was when he talked about his current writing project, an article about Coco, the gorilla who does sign language and just turned 40 this year. “There’s one photo of Coco in her website where she just has her mouth open really wide for some reason,” Lin says, almost cracking a smirk.

Remarkable about the flurry of press coverage on Lin is the mostly absent interest in his background as the son of Taiwanese parents. Lin’s cult popularity seems to have crossed over to predominantly white readers of the twenty-something age group. No one has referred to him as an "Asian American writer," an uncommon phenomenon in these times of ghettoized literary critique where commentators are too often in a hurry to categorize works by people of color as “ethnic literature.” “I’m glad people don’t call me an Asian American writer,” says Lin. “I wouldn’t hate it if someone called me an Asian American writer, it would just be there. I also don’t like people saying I’m representative of a generation or that I’m writing about a generation. To me, that’s the same thing as saying that I’m writing about Asians or I’m writing about anything except those specific people I’m writing about.”

Being “representative” of a culture is often an unfair burden placed upon writers of color, and certainly, one can’t blame Lin for wanting to avoid this trap. One might even credit him for defying expectations of what “minority literature” should be like, as revealed, for example, in a generalization proffered by the London Review of Books (“Though [Lin] is the son of immigrants, he doesn’t write mutigenerational sagas or dwell on cultural differences”). However, there is still something rather unsettling about Lin’s complete disavowal of race.

For example, in a 2007 interview with Bookslut, Lin made the following statement: “An Asian who is 'proud' of his or her heritage is racist.” His recollection of the statement seemed dim when I brought it up in our interview, but after some prodding, Lin elaborated: “I think every single person is racist if the definition of racist is treating someone differently based on their ethnicity. Because it’s impossible to meet someone and completely ignore the color of their skin or the shape of their face or whatever … everyone is racist to some degree, like, that word doesn’t mean anything to me. I would just prefer not to feel proud of, like, something I have no control over … I would rather feel good about specific things that I’ve done.”

Lin's writing may be innovative (some say gimmicky) and his characters believable, yet I still find it hard to take completely seriously. His work’s entrenchment in today’s popular culture, narrow appeal to a young demographic, and accompanying publicity stunts make it difficult to foresee its staying power. Of course, Lin still has plenty of time to make his mark. But unless he comes up with something more mature, he might just be someone readers will eventually outgrow.

Comments