A recent conference on the “memory industry" convened Art Spiegelman, Philip Gourevitch, and Ian Buruma, among others, to discuss the shadowy recesses of our past. The Holocaust was prominently featured, as were Rwanda and Iraq. But the Asian continent -- think of the violence in 20th-century Vietnam, Korea, Cambodia, and China for starters -- was almost entirely neglected. One need not play "oppression Olympics" (a.k.a. "competitive victimization") to smart at the omission: not the inattention of a conference but the pervasive absence of Asia from our view of history and human rights.

In this respect, the publication and phenomenal success of The Rape of Nanking was anomalous. The 1998 book introduced the English-speaking world to a pivotal incident from the Sino-Japanese Wars, illuminating by extension the lesser-known geographies of World War II.

With The Rape of Nanking, writer Iris Chang, then 29 years old, attained literary renown and unwittingly energized an international, postwar movement for redress. So it came as a shock when, just six years later, Chang shot and killed herself on the shoulder of a California highway.

Many fans and onlookers interpreted her 2004 suicide as an instance of vicarious trauma -- that Chang could no longer bear the weight of Nanking scholarship and advocacy. But she had in fact moved beyond her famous book, kept busy by the demands of motherhood and new projects. Is it then accurate to see Chang as a temporally dislocated victim of the Nanking massacre? Did she really succumb to postwar politics?

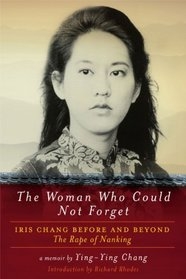

We now have an insider's perspective on these questions, with the recently published memoir of Ying-Ying Chang, Iris's mother. The elder Chang makes her intentions clear: to honor her daughter's life and explain her death as a fatal reaction to psychotropic medications. But even through the protective layer of a mother’s voice, the reader forms distinct impressions of Iris Chang’s character and eventual demise.

Like her book's title, The Woman Who Could Not Forget: Iris Chang Before and Beyond The Rape of Nanking, Ying-Ying Chang's writing is rather artless, and one must abide its unqualifiedly approving, sometimes cloying, maternal tone. But it proves compelling, if unsettling, for readers interested in historiography and Iris Chang's too-brief stint as a heroine of memory.

Iris Chang and her brother were raised in Champaign-Urbana, near the university where her parents were academics. On Mrs. Chang’s telling, the young Iris was precocious and sensitive, traits not unconnected to her overweening adult ambition.

Iris's letters, emails, and poetry, from which her mother quotes liberally, reveal a preoccupation with writerly fame and (im)mortality. By the time she was writing her first book, a scientific biography, Iris was evidently concerned with her own legacy as much as her subject's. In October 1992, she wrote to her mother: "I think it's important for me to write more letters to you to keep a record of events ... After spending a year of research on this book I have learned that the best way to control how history is written is to (1) be a compulsive letter writer, or (2) outlive your enemies."

Two years later, Iris encountered the particular history that would change her life. Having heard about the Nanking massacre from her grandparents, she attended a 1994 conference on the Sino-Japanese Wars. There she was gripped by photographs from Nanking and subsequently, with the blessing of her agent and publisher, immersed herself in what would become The Rape of Nanking.

Ying-Ying Chang recounts her daughter's early reaction to the source materials:

Iris told us that the most difficult thing was to read one case after another of the atrocities Japanese soldiers had committed in Nanking in 1937-1938. The Japanese soldiers carried out the rapes, tortures, and executions of innocent women and men with unspeakable cruelty. She read hundreds of such cases. She felt numb after a while. She told me she sometimes had to get up and away from the documents to take a deep breath. She felt suffocated and in pain.

Perhaps more significantly, Chang's project was freighted with Japan’s postwar avoidance, its failure to grapple with an imperial past. According to Ying-Ying Chang, Iris received threats and hate mail in connection with the book, and one pre-publication episode confirmed her worries about harassing censorship.

In late 1997, Iris wrangled with Newsweek over the deferred printing of a Rape of Nanking excerpt. She (and her mother) attributed the repeated postponement to pressure from Japanese advertisers: “Although Newsweek denied that the pull-out of the Japanese ads was the reason for the delay, no one could explain why the December 1 issue [in which the excerpt was finally published] had not a single Japanese ad, whereas the November 17 issue had carried double the usual number of such ads.”

A curious episode indeed and one of several (surprisingly) riveting publishing dramas in Mrs. Chang's book. Another concerns Iris’s dealings with the Kashiwashobo press, which planned to publish The Rape of Nanking in translation. Her mother describes a long back-and-forth between Iris and the Japanese publishing house. Iris believed that "the vast majority of the [editing committee's] annotations were not corrections of errors, but merely additional details of existing facts. Worst of all, according to Iris, many of these annotations were factually incorrect and contradicted several well-established historical accounts of World War II history." When Iris got wind of Kasihwashobo’s plan to release a separate, critical book concurrent with hers, she terminated the relationship.

Notwithstanding the reality of the Japanese right, one questions Iris's tendency to equate any criticism of her book with revisionist denials of the massacre. When Japanese Ambassador Kunihiko Saito baldly opined that The Rape of Nanking "contained many extremely inaccurate descriptions and one-sided views," she wrote to her mother, "Can you imagine what would happen if a German ambassador to the U.S made a parallel statement about a book on the Holocaust?"

For Iris, Nanking and Japan’s related war crimes represented a holocaust of the East, one deserving commensurate attention. After the book, she thus pursued a movie contract with missionary zeal, continuing to evince a double-obsession about the subject and herself:

I met with several famous Hollywood producers last Wednesday. They flew up to San Jose to see me, and one was literally taken aback by my age and appearance. (He was astounded -- or pretended to be -- to meet "such a beautiful author," and later, in a phone conversation, said he had expected me to be older, scholarly-looking, with glasses: "Instead, in walks this lithe, willow [sic] beauty!" he exclaimed.)

Egocentric tendencies aside, Iris Chang was clearly devoted to the story of Nanking and savvy to prioritize film as a vehicle. Unfortunately a deal never materialized, and it is still the case that Nanking and other Japanese war crimes are largely outside our filmic purview.

Lu Chuan's City of Life and Death (2009) attempts to fill this void, telling a dramatized tale of Nanking, 1937. The film is relentlessly violent, as one would expect, and nothing and no one is really redeemed. Only the black-and-white format saves the viewer from the myriad horrors of bloodshed. But the film is also thoroughly gorgeous. Many shots could be frozen as silken silver-gelatin prints like those of Hiroshi Sugimoto.

As at least one critic has already observed, Lu’s film resorts at times to Asian melodrama, but the acting is generally commendable. The tricky task for the audience is caring about the protagonists: Kadokawa, a naive, internally conflicted Japanese soldier; John Rabe, the Schindler-like Nazi official who oversaw the "Nanking Safety Zone;" and the Chinese collaborators who served Rabe. Hardliners like me may not be moved by the suffering of these characters; I reserved my sympathies for the Chinese civilians and prisoners of war -- the true innocents of the City of Life and Death.

Reviews have overlooked what intrigues me most about the film: its structural separation of violence against men and women. The first section follows the massacre of Nanking men, the weary, herded-up prisoners of war who meet creative, sadistic slaughter. Only later, well beyond the crumbled wall of Nanking, in the sanctum of the Nanking Safety Zone, do we find the city’s women. Here they are gang-raped and molested rather than killed, for in the film -- contrary to reality -- few women die. It’s suggested instead that their loss of innocence is worse than ceasing to exist. While male corpses and survivors bear the dirty, bloody marks of war, the few female bodies we see piled in a wagon and pulled out of a comfort station are immaculate in their svelte, pale flesh, not a mark to be found.

Lu's bifurcation of male and female violence undermines the communal annihilation of Nanking. That men are treated one way and women another, and that their suffering rarely overlaps, seems fantastical and at odds with the massacre's ethno-nationalist thrust.

In the final scene, populated only by men, one character offers the pithy, pathetic reassurance that “life is more difficult than death.” This aphorism reflects not only the protagonists’ motivations, but a larger truth about life in war. And Lu hereby speaks obliquely to another, distant death: the mysterious exit of Iris Chang.

Comments