There are no happy endings in Rahul Mehta’s collection of short stories, Quarantine. Like the title suggests, the protagonists, comprised primarily of gay, second-generation Indian American men, are all trapped, fully aware of their metaphorical diseases but ultimately unable -- or perhaps unwilling -- to find a cure. Traversing multiple locations throughout the United States and India, Mehta’s stories deal mostly with failing relationships, family tensions, and neglected friendships. The protagonists are suspicious, callous, and aloof. Ultimately, the most unlikable characters have the most compelling stories.

At times Mehta runs the melodrama high, as in “The Better Person,” in which an angry outburst over a food allergy during a game of Jenga reveals the impending breakup between Deepu and his boyfriend Frank. The title comes from a strained conversation between Deepu and his mother, who asks of their relationship, “Who is the woman?” -- a question Deepu later understands to mean, “Who is the better person?” Unhappy with his relationship, Deepu suggests to Frank that they sleep with other men to break the monotony. When he ends up seducing a much younger man, he describes the decision as though it were fated, as though he has no control over his actions: “It’s happening. I can tell it’s happening, and there is nothing I can do to stop it.” In attempting to absolve himself of any blame, he is unwilling to recognize that he is not “the better person.”

Despite his characters’ occasional outbursts, Mehta shows a keen sense of restraint, of words left unspoken. Alienation and miscommunication are common themes throughout the collection. Some characters face literal language barriers, such as Ranjan who, in the comparatively lighthearted “Citizen,” fails her US citizenship exam due to her inability to speak English. But most characters merely cannot vocalize their thoughts and emotions, speaking instead through confused actions -- as with Deepu above -- or through confusing riddles. “What We Mean” follows two writers, Carson and Parag, also on the brink of a breakup. Parag’s incessant wordplay in the form of unintelligible notes causes a widening rift between the two. For example, he leaves notes for the neighbors to move their car, inexplicably transforming “s’il vous plaît” into “Sylvia Plath.” The notes are so far removed from the intended meaning that even Carson cannot understand them. “No one can.”

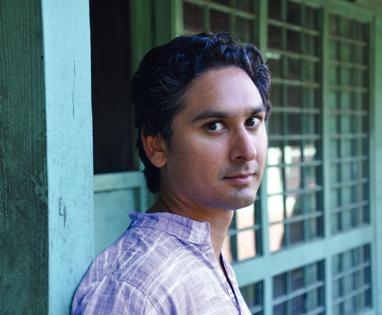

Rahul Mehta

The penultimate story, “Yours,” is in my opinion the masterpiece of the collection. Here Mehta shows a highly developed sense of subtlety as he follows an unnamed protagonist, his white boyfriend Don, and Don’s older black dance instructor Antwon. Knowing that Antwon had previously paid Don for sex as part of a project funded by an NEA Individual Artist Grant, the protagonist must navigate an uneasy relationship rife with sexual tension. Where are they really going, what are they really doing, when Don and Antwon go out for their routine dinner and drinks?

Antwon here seems to represent a faltering sexual power. Though he is an acclaimed avant-garde artist, his heyday has long passed; when he performs for a conservative audience in an upstate New York university, his confidence is clearly shot. In a scene prior to the performance, Antwon cuts himself shaving, and the protagonist helps place a band-aid on his cut. Though Antwon still asserts his dominance -- slapping the protagonist’s ass and calling him “squirrel” -- he is described as “still taut but beginning to soften with age.” As the protagonist touches him, “allowing my finger to drift down his neck, across his chest, circling the gray hairs,” Antwon reacts with wordless confusion. Later, after the show, Antwon is more pitiful: “did I feel his hand briefly grasp the cuff of my pajama? Did I hear […] a murmur, a whisper? Squirrel. Stay.” These two scenes suggest a reversal of the sexual power dynamic between the two characters, revealing the pathetic and insecure man that Antwon, previously characterized as proud and pretentious, has become.

Mehta’s stories work best when his characters say the least. His characters’ disenchantment is easily relatable: we have all experienced those moments right before a breakup when we refuse to speak because words would mean acknowledging the infection. As the character Parag says, “I cannot bear the things I must say, day after day, and the words I must use to say them,” summarizing quite succinctly the pervasive malaise in the collection.

Eric Zhang has a background in Asian American studies, art, and visual culture. He currently lives in New York, where he works at NYU and MOCA.

Comments