Imaginatively illustrated using a mix of paper-cut collages, sketches, portraits and old family photographs, The House Baba Built by Caldecott Medalist Ed Young tells the story of the author's childhood in war-time Shanghai. Although it is being billed as a children's book, The House Baba Built will appeal to multiple audiences. Born in China, Ed Young moved to the United States of America in 1951 to study architecture but was quickly drawn to the world of art instead. He has written and illustrated several picture-books since 1962, such as a Chinese version of Little Red Riding Hood, Lon Po Po, The Emperor and the Kite, and Seven Blind Mice. The House Baba Built is written in collaboration with Libby Koponen. The memoir is both a tribute to Young's father and a cultural and historical document on the effects of the Second Sino-Japanese war.

In 1931 the world is a bleak place to live in. Young notes in his foreword that it is “... two years after the stock market crashed in America, two years into the greatest depression the world had ever known.” This is the world that Ed Young is born into and soon after, “China was invaded, leaving unknown numbers of people homeless.”

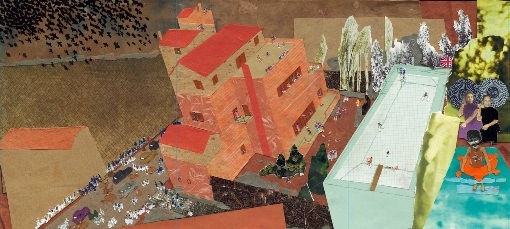

Worried for his family's safety, Young's father, an engineer by profession, convinces a rich landowner to let him built a brick house on his land, which happens to be in the safest part of Shanghai -- near the embassies. In return, he asks only that his family be allowed to live there for twenty years -- long enough for his five young children to grow up and for the war to run its course. Remarkably, the landowner agrees and “Baba,” as Young calls his father, sets about designing and building the house.

The house he builds is a fortress at first and, as the years go by, Young and his siblings' fertile imagination transforms the house into an entire world unto itself. These worlds are fantastical creations where rocking chairs turn into horses and terraces turn into skating rinks. Much like the house itself, these pages are like little rooms that, when opened up, reveal a hidden anecdote or observation. The book also contains street maps, floor plans and pictures of the house as it stands today.

While the story is told through Young's eyes and is a homage to his father, it is the house itself that is the story's main character. Just like its inhabitants, who change over the years, the house also undergoes several changes. As new refugees move in with the Youngs, Baba adds rooms and wings to the existing structure to house the incoming residents. The first to arrive are Young's aunt, uncle and two grown-up cousins. The terrace, which doubled as a skating rink for Young and his siblings, is converted into an apartment for the new arrivals. Later on with the arrival of the Leudeckes, a German couple and their baby, Jean, Baba puts together an apartment for them out of the children's bedrooms.

The vignettes and anecdotes paint a picture of a carefree childhood where days were spent fighting crickets, trading silkworm eggs, riding bikes in the empty swimming pool and picnicking. These stories are told in simple, straight forward prose. However, lest we walk away from this book feeling that it paints a glossy and sheltered pictured of war-time China, Young chooses to remind us of the violence outside in small ways.

At first, it's the news of war arriving through the short wave radio which prompts the young Ed to “sling anything the right shape over my shoulder and strut from room to room.” Later on, it's the distant fighter planes swooping at each other in the sky, curfews, the arrival of refugees and finally sirens that announce the commencement of bomb attacks. But more subtly, it is the scarcity of food that sends the message home as when Young writes, “While the adults feasted, we five watched from the darkened stairs, hoping for leftovers -- especially leftover meat.”

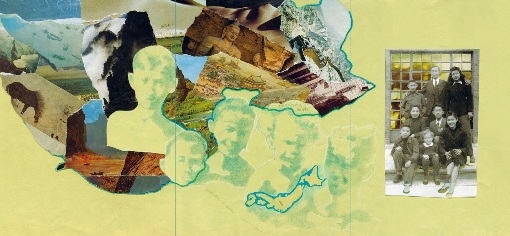

While the stories are humorous and poignant, what is most unique about the book is Young's choice of artistic materials. Using a creative blend of collages, old photographs and pencil and ink portraits to tell his story, the author implies that one's memory of events does not really present the truth of those events. What we remember is colored by the mind's ability to reorder events, assign personal meanings to them and revise entire sequences to fit in with our own perception. Young himself remarks in his Author's Note that he “also learned to come to terms with the limits of human efforts in recreating reality -- any human creation, no matter its completeness or point of view, is at best a mere fragment of life itself.” In keeping with that idea, Young populates the pages with family portraits right next to cut-outs and photographs pasted onto sketches.

The world that Baba created for his children allowed them to both withdraw from the horror of war as well as observe it from a safe distance. Ultimately, Young's memoir is a story of hope and of a father's decision to protect his family to the best of his ability.

Anisha Sridhar is a journalist and writer who writes all day and sometimes gets paid for it.

Comments