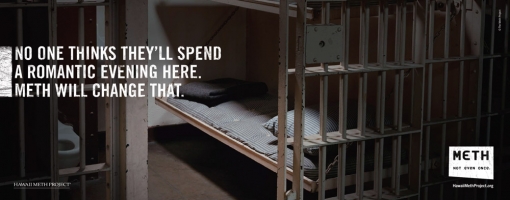

Cindy Adams. Photos from Hawaii Meth Project

by Cat Kim

The Hawaiian Islands are known to many as the perfect paradise: tropical beaches, beautiful weather, and those fun grass skirts. But behind the blissful veneer, Hawaii struggles with methamphetamine use. In 2008 44 percent of the state’s drug-related treatment admissions were related to methamphetamine, surpassing admissions related to marijuana, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (a public health agency within the Department of Health and Human Services).

Cindy Adams is working to change that. As executive director of the Hawaii Meth Project, a non-profit organization that aims to reduce methamphetamine use among teens and young adults, her goal is to communicate the risks and affects of meth abuse through hard-hitting media campaigns and community outreach and education. I recently asked Cindy about Hawaii’s struggle with this highly addictive and destructive drug and how the program is having an influence on Hawaii’s youth.

What prompted you to become involved with the Hawaii Meth Project?

Like many states across the nation, Hawaii has a significant methamphetamine problem. “Crystal meth”, or “ice,” as it is known in Hawaii, has been around since the ‘60s. It is our biggest drug problem and results in enormous downstream costs including treatment, incarceration, foster care, healthcare, and lost productivity to employers. I became involved because meth directly impacted my family, and I wanted to do something about it.

When did you learn Hawaii had a meth problem?

I grew up in Japan and Hawaii. I moved to the Bay Area when I graduated from college, lived there for over 20 years, and then moved back to Hawaii in 2004. A couple of years later, we learned that someone in our family was smoking ice. It had an immediate and devastating effect on the entire family. We didn’t anticipate it or recognize it for what it was, and it was like slamming into a brick wall. It’s one thing to have someone tell you what this drug does to families; it’s a nightmare to live it. It still affects our family and for some, there will be lifelong implications. Methamphetamine has this immense ripple effect beyond the user.

Considering Hawaii’s large Asian American population, have you noticed the effects of methamphetamine abuse impacting this community as well?

I am Japanese and meth impacted my family. It would be impossible for this drug not to affect the Asian American community in Hawaii given it is the majority. We have a diverse and somewhat complex culture in the islands, and Hawaii struggles with multigenerational meth use. It’s particularly challenging to break this cycle, to change the social norm. That’s why the Hawaii Meth Project’s integrated approach -- large-scale public service messaging and community outreach and education -- is so vitally important. We are focused on teenagers because risky behavior starts at a young age. But we also reach beyond teenagers to the broader community, educating on a larger scale, so we can help change the social norm.

What kind of response have you received from the community?

The response from across the state has been overwhelmingly positive and supportive. So many people in Hawaii have been affected by crystal meth, especially if you consider its 40-plus year history in the state. One indicator of this incredible community support is we see teenagers taking greater ownership for peer outreach and raising the level of dialogue in their family, their group of friends, and in school.

What impact has the Hawaii Meth Project had thus far in the community?

We perform an annual survey among teenagers across the state, with the first benchmark survey conducted in 2009 prior to launching the program. When we did the second survey in 2010, a year later, we saw very encouraging results. The changes in teen attitudes toward meth were significant. Teenagers are increasingly aware of the risks of using meth, strongly disapprove of taking the drug even once or twice, and are more likely to discuss the subject with their parents. The data also showed that increasing numbers of teens say their friends would give them a hard time for using meth. The 2011 survey results will be posted on our website this summer.

What is your personal goal for the Hawaii Meth Project?

The impact of this drug to users, families, and communities is nothing short of devastating. Children who can’t be cared for end up in foster care. Meth creates a huge socioeconomic burden on states. My hope is that we are successful in breaking the cycle of methamphetamine addiction in Hawaii, and educating teenagers is key to accomplishing this. If we can reduce the number of people who start using this drug, the size of the using population will begin to decrease, which will help drive down the overwhelming burden of treatment, incarceration, crime, foster care, etc. Equally important is educating and raising awareness with the community at large. We need everyone’s support if we are to change the social norm. To get more information on the Hawaii Meth Project, view its media campaign and outreach efforts, or make a donation to support these efforts, visit www.hawaiimethproject.org.

Cat Kim is Hyphen’s marketing associate. She works for the Siebel Foundation, which founded the National Meth Project.

Check out all of the profiles in our APA Heritage Month series.

Comments