Bethany Li speaking at a rally in 2009, when the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (with co-counsel South Brooklyn Legal Services) sued New York City over its failure to reveal the devastating impact a rezoning would have on Brooklyn's working-class Sunset Park community. Photo courtesy of South Brooklyn Legal Services.

"NAASCon exists because APA students are not apathetic, because each generation or wave of immigration should not have to face a new set of stereotypes, because we are Americans no matter what anyone says, because campus issues recur everywhere, because we will not be denied our history and identity, because Joseph Ileto was a son and a brother, because Wen Ho Lee spent nine months in solitary confinement, because glass ceilings are meant to be broken, because accents do not equate to inequality, because civil rights are not optional, because the backlash against affirmative action has not ended, because we will not be invisible, because we remember the concentration camps, because we know why we cry -- BECAUSE WE CAN. BECAUSE WE MUST."

My friend Owen Li wrote this ten years ago to serve as the mission statement to a group we, along with about 15 other college students, had just founded: the National Asian American Student Conference, or NAAScon.

NAASCon began with a simple question: why had there never been a national Asian American student group? There were regional ones (MAASU, ECAASU) and also ethnic-specific ones (FIND, ITASA, KAASCON). The idea was to connect Asian American students around the country and harness their enthusiasm and energy to create a meaningful, nationwide movement.

It started as a forum where Asian American student activists everywhere could meet, share resources, coordinate campaigns and learn from one another about community issues. Over the years, it stood at the forefront of major Asian American student campaigns, including the 2002 boycott of Abercrombie & Fitch for producing tee shirts featuring stereotypical caricatures of Asians; supporting HR 333, a 2003 bill to provide federal funding for institutions of higher education with sizeable Asian American populations; and a 2005 campaign against the Jersey Guys, New Jersey DJs who made inflammatory remarks toward Asians and Asian Americans on a local radio station.

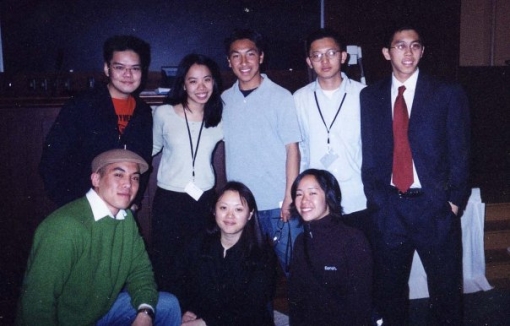

Li (top row, second from left) with members of NAASCon's founding board in 2003 in Philadelphia.

Beyond these "reactive," short-term campaigns were ongoing projects like developing a clearinghouse of materials for students who wanted to create Asian American Studies programs at their schools and a database of Asian American student and community groups. The group also held two conferences -- in 2004 at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles and in 2008 at Emory University in Atlanta -- that drew hundreds of students from across the country.

Bethany Li was the heart of the organization for many of the years of its existence (it has been inactive since 2008).

I met Li in 2001 after we had both finished our second year of college and were interns at a social networking website called AsianAvenue.com in New York City. It was my first time living outside of California, and I didn't know a soul in the city. I didn't sleep the first two days I was there, so terrified was I of getting robbed in my apartment (I should add it was in Chelsea and just doors from a police station).

Li, on the other hand, was the embodiment of courage. I was astounded that this girl -- 5-feet-tall and so youthful looking that she was once asked by a flight attendant "Where’s your mommy?" -- could be entirely at ease on the subways, which I considered a gauntlet so perilous I would rather walk 80 blocks.

It was from a similar sense of awe for one’s peers that NAASCon was born. During that summer we met a larger group of community-minded Asian American students who were in Washington, DC, as part of the Organization of Chinese Americans program, which places college students at federal agencies and nonprofit groups for summer internships. They were smart, funny, and poised, and they cared about vital issues to the community. They were from huge universities, like I was, but they were also from tiny schools I had never heard of -- like Amherst, a small liberal arts school in western Massachusetts that had no Asian American Studies program and barely any Asian American Studies classes, where Li was from. We were both inspired by the students we met that summer. "You had all these different people who were pretty well-versed in these different issues because of their backgrounds and their schools," she recalled recently. "I learned a lot just from talking to people that summer."

She wanted NAASCon to provide that experience on a larger scale. "We saw how much fun and really how beneficial it was to get to know so many really great APA student activists from all over the country," she said. "Just being able to connect with other people on other campuses who were fighting similar issues was important, especially people who might feel isolated on campuses, like they're the only one talking about issues affecting Asian American communities. We wanted to make sure it was something others had access to, not just this small group of interns. NAASCon was a way to connect all of these different people to make more of a community of Asian American activists."

Clifford Yee, who we met that summer in DC (and who is now a youth program coordinator at Asian Health Services in Oakland), attended the 2004 conference at USC and "was amazed by the number of students from across the country who attended and by the workshops and speakers that were part of the program. Bethany is truly an unsung hero for being one of the founding members of NAASCon and helping Asian American students across the nation have a voice."

Many who have worked with Li are impressed not only with her zeal for the organizing the Asian American community but also her remarkable humility. "I have never known Bethany to feel she needed praise for her accomplishments," Yee said. "She would always put it on her fellow team members."

Li (second from right) with former NAASCon board members in New York City in 2009.

May Yang, a member of the 2003-05 NAASCon board (now a research associate at the Council on Foreign Relations), says Li was an exceptional leader. "She was always guided by a vision and knew how to work with each individual member of the group toward an important objective. She was also very nurturing as she often took the time to mentor board members and provided the space for others to learn and take ownership in initiatives."

Minnie Yuen was a student at Wellesley organizing protests against Abercrombie & Fitch when she first met Li, who was coordinating similar efforts across the nation. "At the time, she was at Amherst, where there were no Abercrombie stores, and yet she was dedicated to making this movement louder and bigger," says Yuen (now a lawyer for the federal government). "From the start, she saw the bigger picture -- creating a larger network in order to make our voices were heard. She knew the power of numbers."

Yuen tells a story that illustrates Li's ability to inspire others: "The day of the Abercrombie protests in Boston, an Asian American man in his late thirties joined our protest. No one knew who he was, but he was very enthusiastic, and he had brought his one-year-old son with him. His son, from his stroller, was protesting right there with us and chanting along with our chants. It really didn't surprise me when I found out later that the man was Bethany's uncle and the baby was her cousin."

Today, Li regards NAASCon with characteristic humility along with a hint almost embarrassment from her perspective as a staff attorney at the Asian American Legal Defense Fund in Manhattan. She works on anti-displacement, anti-gentrification, community planning, and environmental justice pertaining to lower-income communities of color. Zoning issues; land-use policies affecting working-class families; coalitions with tenants, workers, and organizers to fight city policies that displace working-class families: it's perhaps understandable that given the things she works on today she readily calls the Abercrombie protests -- which she worked so tirelessly on -- "a fluffy campaign." But she says her experience collaborating with a broad cross-section of students through NAASCon taught her many of the skills she uses in her work today: working in coalitions, thinking through strategy and how to convince people, advocacy.

She hedges about what real impact she or NAASCon has had. "I was talking to a former board member the other day about this, and he said, 'At the very least we got people talking.' Even though now we look back and say there are a lot more things that we could have been and should have been demanding, I think it also showed that college students and an organization like NAASCon could be important in terms of organizing and getting people connected into a bigger movement."

The NAASCon Board at the 2004 conference at USC.

Li sees NAAScon as a way to potentially organize students around deeper, more substantial issues. "College students can be so passionate and excited and active -- they aren’t totally jaded yet!" she laughs. "There’s an excitement and energy about the type of mobilizing that can take place that NAASCon tapped into." And issues of media representation (like the Abercrombie & Fitch shirts) are most likely to incite college students, she says. "That’s how some students become involved and start to learn about bigger issues. The first entry point is sometimes on these types of more reactive issues."

Today, she suspects that not much has changed in terms of what’s important to Asian American students; she hears interns around her office talking about the same issues as when she was in college. Some current students have also approached her recently about reviving NAASCon, an endeavor she supports.

She insists that the 24-7 connectivity of the Internet can't replace the tangible relationships that were built through in-person collaborations on issues that people care deeply about. "You can connect online, but part of why we’re all still friends is because we've had not just political discourse but also social interaction. That's an important point -- the friendships and relationships we've made as a result of learning about these issues together and working together has kept us in touch."

But a new NAASCOn would have to be a more sustainable one. In the old model, there was burnout, there was turnover endemic to any student organization, there was the constant issue of funding for the conferences.

Ultimately, she says, NAASCon's greatest strength was providing ways for Asian American student leaders and activists to connect -- and she believes that need remains as imperative as ever. She recalls a keynote speaker at one of the conferences telling her that she had never been to a student conference at which the participants were so engaged. "That's exactly what we wanted and envisioned when we started NAASCon,” she said. "That’s the type of organization we wanted to build."

Lisa Wong Macabasco is Hyphen’s managing editor and was a co-founder of NAASCon.

Check out all of the profiles in our APA Heritage Month series.

“NAASCon exists because APA students are not apathetic, because each generation or wave of immigration should not have to face a new set of stereotypes, because we are Americans no matter what anyone says, because campus issues recur everywhere, because we will not be denied our history and identity, because Joseph Ileto was a son and a brother, because Wen Ho Lee spent nine months in solitary confinement, because glass ceilings are meant to be broken, because accents do not equate to inequality, because civil rights are not optional, because the backlash against affirmative action has not ended, because we will not be invisible, because we remember the concentration camps, because we know why we cry - BECAUSE WE CAN. BECAUSE WE MUST.”

My friend Owen Li (no relation) wrote this ten years ago to serve as the mission statement to a group we, along with about 15 other college students, had just founded, the National Asian American Student Conference, or NAAScon.

NAASCon began with a simple question: why had there never been a national Asian American student group? There were regional ones (MAASU, ECAASU) and also ethnic-specific ones (FIND, ITASA, KAASCON). The idea was to connect Asian American students around the country and harness their enthusiasm and energy to create a meaningful, nationwide movement.

It started as a forum where Asian American student activists across the country could meet, share resources, coordinate campaigns and learn from one another about community issues. Over the years, it stood at the forefront of major Asian American student campaigns, including the 2002 boycott of Abercrombie and Fitch for producing tee shirts featuring stereotypical caricatures of Asians; supporting HR 333, a 2003 bill to provide federal funding for institutions of higher education with sizeable Asian American populations; and a 2005 campaign against the Jersey Guys, New Jersey DJs who made inflammatory remarks toward Asians and Asian Americans on a local radio station.

Beyond these “reactive,” short-term campaigns were ongoing projects like developing a clearinghouse of materials for students who wanted to create Asian American Studies programs at their schools and a database of Asian American student and community groups. The group also held two conferences—in 2004 at USC in Los Angeles and in 2008 at Emory University in Atlanta— that drew hundreds of students from across the country.

Bethany Li was the heart of the organization for many of the years of its existence (it has been inactive since 2008).

I met Bethany in 2001 after we had both finished our second year of college, when we were both interns at a social networking website called AsianAvenue.com in New York City. It was my first time living outside of California, and I didn’t know a soul in the city. I didn’t sleep the first two days I was there, so terrified was I of getting robbed in my apartment (I should add it was in Chelsea and just doors from a police station).

Bethany, on the other hand, was the embodiment of courage. I was astounded that this girl—5-feet-tall and so youthful looking that she was once asked by a flight attendant “Where’s your mommy?”—could be entirely at ease on the subways, which I considered a gauntlet so perilous I would rather walk 80 blocks.

It was from a similar sense of awe for one’s peers that NAASCon was born. During that summer we met a larger group of community-minded Asian American students who were in Washington DC as part of the Organization of Chinese Americans program, which places college students at federal agencies and nonprofit groups for summer internships. They were smart, funny, and poised, and they cared about vital issues to the community. They were from huge universities, like I was, but they were also from tiny schools I had never heard of—like Amherst, a small liberal arts school in western Massachusetts that had no Asian American Studies program and barely any Asian American Studies classes, where Li was from. We were both inspired by the students we met that summer. “You had all these different people who were pretty well-versed in these different issues because of their backgrounds and their schools,” she recalled recently. “I learned a lot just from talking to people that summer.”

She wanted NAASCon to provide that experience on a larger scale. “We saw how much fun and really how beneficial it was to get to know so many really great APA student activists from all over the country,” she said. “Just being able to connect with other people on other campuses who were fighting similar issues was important, especially people who might feel isolated on campuses, like they’re the only one talking about issues affecting Asian American communities. We wanted to make sure it was something others had access to, not just this small group of interns. NAASCon was a way to connect all of these different people to make more of a community of Asian American activists.”

Clifford Yee, who we met that summer in DC (and who is now a youth program coordinator at Asian Health Services in Oakland), attended the 2004 conference at USC and “was amazed by the number of students from across the country who attended and by the workshops and speakers that were part of the program. Bethany is truly an unsung hero for being one of the founding members of NAASCON and helping Asian American students across the nation have a voice.”

Many remark about Li’s zeal for the Asian American community and remarkable humility. “I have never known Bethany to feel she needed praise for her accomplishments,” Yee said. “She would always put it on her fellow team members.”

May Yang, a member of the 2003-05 NAASCon board (now a research associate at the Council on Foreign Relations), says Li was an exceptional leader. “She was always guided by a vision and knew how to work with each individual member of the group toward an important objective. She was also very nurturing as she often took the time to mentor board members and provided the space for others to learn and take ownership in initiatives.”

Minnie Yuen was a student at Wellesley organizing protests against Abercrombie & Fitch when she first met Li, who was working to coordinate similar efforts across the nation. “At the time, she was at Amherst, where there were no Abercrombie stores and yet, she was dedicated to making this movement louder and bigger,” says Yuen (now a lawyer for the federal government). “From the start, she saw the bigger picture—creating a larger network in order to make our voices were heard. She knew the power of numbers.”

Yuen told me a story that illustrates Li’s ability to inspire others. “The day of the Abercrombie protests in Boston, an Asian American man in his late thirties joined our protest. No one knew who he was, but he was very enthusiastic, and he had brought his one-year-old son with him. His son, from his stroller, was protesting right there with us and chanting along with our chants. It really didn't surprise me when I found out later that the man was Bethany's uncle and the baby was her cousin.”

Today, Li regards NAASCon with characteristic humility along with a hint almost embarrassment from her perspective as a staff attorney the Asian American Legal Defense Fund in Manhattan. She works on anti-displacement, anti-gentrification, community planning, and environmental justice pertaining to lower-income communities of color. Zoning issues; land-use policies affecting working-class families; coalitions with tenants, workers, and organizers to fight city policies that displace working-class families—it’s understandable that given the things she works on today she readily calls the Abercrombie protests—which she worked so tirelessly on—“a fluffy campaign.” But she says her experience collaborating with a broad cross-section of students through NAASCon taught her many of the skills she uses in her work today: working in coalitions, thinking through strategy and how to convince people, advocacy.

She hedges about what real impact she or NAASCon has had. “I was talking to a former board member the other day about this, and he said, ‘At the very least we got people talking.’ Even though now we look back and say there are a lot more things that we could have been and should have been demanding, I think it also showed that college students and an organization like NAASCon could be important in terms of organizing and getting people connected into a bigger movement.”

Li sees NAAScon as a way to potentially organize students around deeper, more substantial issues. “College students can be so passionate and excited and active – they aren’t totally jaded yet!” she laughs. “There’s an excitement and energy about the type of mobilizing that can take place that NAASCon tapped into a little bit.” And issues of media representation (like the Abercrombie & Fitch shirts) are most likely to incite college students, she says. “That’s how some students become involved and start to learn about bigger issues. The first entry point is sometimes on these types of more reactive issues.”

Today, she suspects that not much has changed in terms of what’s important to Asian American students; she hears interns around her office talking about the same issues as when she was in college. Some current students have also approached her recently about reviving NAASCon, an endeavor she supports.

She insists that the 24-7 connectivity of the Internet can’t replace the tangible relationships that were built through in-person collaborations on issues that people care deeply about. “You can connect online, but part of why we’re all still friends is because we’ve had not just political discourse but also social interaction. That’s an important point—the friendships and relationships we’ve made as a result of learning about these issues together and working together has kept us in touch.”

But a new NAASCOn would have to be a more sustainable one. In the old model, there was burnout, there was turnover inherent to any student organization, there was the constant issue of funding for the conferences.

Ultimately, she says, NAASCon’s greatest strength was providing ways for Asian American student leaders and activists to connect—and she believes that need remains as imperative as ever. She recalls a keynote speaker at one of the conferences telling her that he had never been to a student conference at which the participants were so engaged. “That’s exactly what we wanted and envisioned when we started NAASCon,” she said. “That’s the type of organization we wanted to build.”

Lisa Wong Macabasco is Hyphen’s managing editor and was a co-founder of NAASCon.

Comments