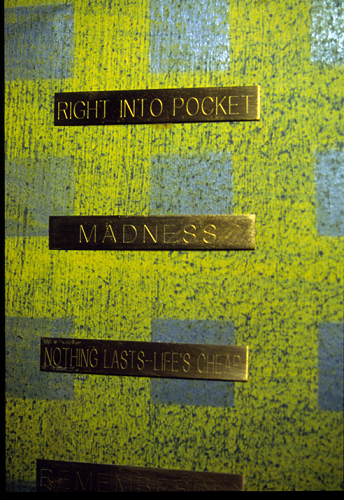

What strikes

you first about Carlos Villa’s artwork is the abundance of lines. Sharp and

straight, they slice through his massive wooden canvases like pinstripes, and cross

like dense city grids. The curved ones layer on top of another, tracing the musculature

of a face, or worming around a canvas seemingly aimless. The work is abstract -- all

form and no referents at first glance -- until certain signs begin to reveal

themselves. Above an intersecting axis hangs a fedora, a symbol of an early

generation of Filipino men who migrated to the West Coast. Alongside a grid are

street names -- Kearny, Montgomery, Washington -- names that mark the vanishing

geography of Manilatown, San Francisco. There’s history in these pieces -- a

Filipino American history of migrants, empire, and selfhood -- but its traces

only emerge after you look closely.

Villa’s artwork

is the subject of the recently edited collection Carlos Villa and the Integrity of Spaces. Theodore Gonzalves,

the book’s editor and a professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore

County, isn’t coy about his opinion of Villa. He is, Gonzalves writes, the most

significant US-based visual artist of Filipino descent of the twentieth century. Others in the volume

attest to Villa’s impact. Moira Roth describes Villa’s presence in the Bay Area

as “casting spells for […] two decades,” not only as a superb artist but as a

legendary teacher. And David A. M. Goldberg, one of the artist’s collaborators,

compares Villa to Public Enemy and graffiti artists, grounded as all three are

in repurposing the idioms of style and the streets. Yet, for the most part, in

the halls of academia (in art history and ethnic studies departments, alike), Villa’s

work has gone unnoticed. Carlos Villa and

the Integrity of Spaces tries to correct that through a series of critical

essays and artistic tributes to his career, both from folks in the academic

world and from long-time friends and activists.

Villa grew

up in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district, in what he describes as “a Filipino

ghetto side by side with a Japanese ghetto, in the middle of a Black ghetto.” Born

in the immediate aftermath of the Tydings-McDuffie Act, which reclassified

Filipinos from “US nationals” to “aliens,” Villa’s art explores this formative era

of Filipino settlement in the US with an eye for both political critique and

communal remembering. And though his projects celebrate that earlier generation

of immigrants, Villa’s engagement with the past is never wrought by sentimentality. Gonzalves explains, “Villa is unsparing [with]

the flaws that he saw in many of his parents’ generation -- whether it had to

do with compulsive gambling or womanizing or alcoholism. […] Of

course, he’d be the first to tell you that his parents’ generation lived and

worked in a time when racism was the law of the land.” In his

installation series My Uncles

(1993-96), for instance, Villa used the metaphor of “doorways” to comment on the

constantly shifting immigration policies toward the Filipino community; quite

literally, too, framed doorways, painted black and affixed with fedoras and photos

of the manong generation, stood in

the middle of a gallery, deliberately leading the spectator nowhere.

It took years,

however, before Villa developed an aesthetic that could meaningfully engage

Filipino identity. Villa’s earliest work was born out of San Francisco’s

abstract expressionist school, which, despite its ethos of freeing the artist

from formal conventions, still constrained his ability to explore the various

facets of his cultural roots -- tribal, national, and regional. Using different

media and materials, interestingly, is what finally allowed him a way in. In an

interview with Margo Machida, Villa explains, “I started using blood along with

my acrylic paint… [as well as] shells, hair, broken mirrors. I started

extending what I knew of modernism to what I just discovered about these

cultures. And in some way, I was trying to bring about an answer or a way that

I could become Filipino American.” In Worlds

in Collision (1994), Villa makes another revealing comment about his

process: “I have always striven for a gumbo, for a creolization of aesthetics

in my own work.”

That

“gumbo” approach to aesthetics, in a way, describes Villa’s ideas on art

education. Since 1969, Villa has taught at the San Francisco Art Institute,

where he has been a pioneer and tireless advocate of multicultural art

education. To be sure, Villa’s “multicultural” isn’t limited to a tepid politics

of inclusion -- what Goldberg describes as the soft multiculturalism of

“sharing food, fashion, and tunes.” His is a far more radicalized

multiculturalism that begins by recognizing the intersections between different

communities of color. Gonzalves explains that Villa’s attempts at fleshing out multicultural

art history had “less to do with adding brown faces to predominantly white

spaces,” and more to do with community building across the city.

So why

have critics overlooked Villa’s body of work? Why is not that complicated, Gonzalves

insists, and is symptomatic of a broader erasure from American public memory of

US imperial relations to the Philippines. “Every academic discipline still

functions much like those guilds of the past -- one group of specialists

training another,” Gonzalves tells me, and “[i]f most ‘Americans’ have no idea

about the meaning and context of events like the Spanish-American or US-Philippine

Wars, you can bet that art historians would know much less.” Carlos Villa and the Integrity of Spaces

is an important book for that reason alone: it not only celebrates the work of

an artist and educator who has inspired so many, but it gives us a way to

engage the “political consciousness” of even Villa’s most abstract art. You can’t

see Tydings-McDuffie, Manilatown, and the manongs

of Kearny Street in the lines of Villa’s giant canvasses, until you learn to

read its signs.

(Visit

Carlos Villa’s website

for more information)

* * *

Manan Desai recently completed his PhD at the University of Michigan, and currently serves on the board of directors for the South Asian American Digital Archive.

Comments