Why would anyone pick a

500+ page novel for leisure reading? Die-hard fans of the Amitav Ghosh brand of

story-telling might point to an implicit answer tucked in the last few lines of

his voluminous book: “The picture cost more than I could afford, he said, but I

bought it anyway. I realized that if it were not for those paintings no one

would believe that such a place had ever existed.” Like the painting of Canton

that Neel, one of the main protagonists in Ghosh’s novel, buys to savor his memory

of the place, the sheer visual quality of Ghosh’s narrative saves this

otherwise digressive, rambling, tome.

The second part of

Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis-trilogy, River of Smoke, turns out to be an

expansive canvas containing intricate images of mundane lives in Canton

(Guangzhou), the city of love, lust, and pleasure, around 1938-39, the year the

First Opium War started. The painting memorializes the Fanqui-town (the

settlement of the foreigners) that was destroyed during the Second Opium War

(1956-60). Ghosh weaves the core of the novel around the rivalry between the

British Imperial power and Lin Zexu, the Chinese Commissioner entrusted by the

Emperor with the responsibility of eradicating the smuggling of opium into

China.

The novel narrates the

journey of a Bombay-based, Parsi entrepreneur, Bahram Modi, to Canton in search

of fortune through opium trade and his love for a Chinese boat-woman, Chi-mei.

The city of Canton does not merely serve as a backdrop in the unfolding human

drama but acts a central protagonist that determines the fate of European,

Armenian, and Indian entrepreneurs. Neel, who was a former aristocrat landowner

in Bengal and who was turned into a convict by the British on the charges of

forgery, jumps Ibis, the ship

transporting indentured laborers from India to Mauritius, and eventually

escapes to Canton to take up employment with Bahram Modi.

In the first volume of

the Ibis-trilogy, Sea of Poppies, which terminated at

the Bay of Bengal, Ghosh narrates several characters’ ordinary, impoverished

lives changing irrevocably under the impact of British colonialism in India.

While the first part ended with the indentured Indian laborers on board Ibis entering the Bay of Bengal, the

second part begins with festivities in a make-shift temple atop a mountain in

Mauritius. Young and adult alike ask survivor Deeti to recount how men managed

to evade the British guards and take to the sea on a boat. This supernatural

moment of escape acts as a pivot for Ghosh’s realistic narrative to unfold.

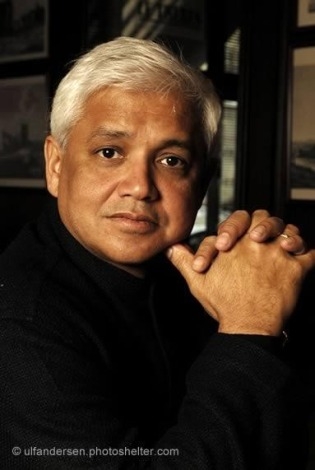

Amitav Ghosh

The motif of travel across

historical space and time -- the hallmark of Ghosh’s writing -- is rehearsed

here, too. The novel narrates the story of three ships -- Ibis, Anahita, and Redruth -- and a body of landmasses --

Great Nicober, Canton, Singapore, and Port Louis in Mauritius. In the process, Ghosh

manages to present a grand history of the evolution of these geographical

spaces. Take for example, his description of Singapore’s emergence as a major

trading port at the expense of Malacca, which had witnessed a cosmopolitan

engagement between different races, languages, and religions. The intervention

of the British seems to destabilize an older fluid notion of culture as new

rigid boundaries are put in place:

[Bahram]

began to understand why several businessmen of his acquaintance had recently

bought and rented godowns and daftars in Singapore: it seems very likely that

the new settlement would soon overtake Malacca in commercial importance. This

evoked mixed emotions in Bahram: he has a suspicion that this British-built

settlement would not be an easy-going place like the Malacca of old, where Malays,

Chinese, Gujaratis and Arabs had lived elbow to elbow with the descendants of

the old Portuguese and Dutch families: Singapore had been so designed as to set

the ‘white town’ carefully apart from the rest of the settlement, with the

Chinese, Malays and Indians each being assigned their own neighborhoods -- or

‘ghettoes’ as some people called them.

The River of Smoke, like Ghosh’s earlier

works, e.g. In An Antique Land,

traces a pre-/early colonial world where cultures and civilizations seemed to

have interacted more fluidly engendering a cosmopolitan environment. While the

validity of such cosmopolitan claims could be challenged, it’s fascinating to

read the process of exchange and entanglement between human beings before the

advent of capitalist modernity that erected boundaries between cultures and

civilizations. Ghosh’s narrative charts how dialogues between civilizations

rupture once the western notion of Free Trade and profiteering is allowed a

free reign without any regard for morality.

Apart from exploring

the process of exchange between human beings, River of Smoke narrates the emergence of an incipient global

ecological consciousness. Fitcher Penrose-owned Redruth’s voyage around the world in search of rare plants that

could adapt and grow in England marks the inauguration of a new way of being

global. The botanical explorations also bring to focus the sharp rivalry

between the European imperial powers launching expensive undertakings in search

of rare plants in places like China that had closed off much of its gardens

from harvesting by the Europeans. Along with imperialists, there were botanical

entrepreneurs like Penrose who scoured the earth for exotic plant varieties.

Ghosh’s ambitious novel

is a capaciously drawn anthropologist’s account. The spacious description

serves to create what Roland Barthes had termed a “reality effect,” an illusion

of reality of life in an era that can best be recreated through fictional

reconstruction. There are numerous moments in the narrative -- e.g., the

description of the smuggled dresses in the ‘Wordy Market’ -- that can flag the

reader’s interest. However, the innumerable digressions do not help in

capturing the unwavering attention of the reader. Yet, at the center of Ghosh’s

narrative is a very simple human drama -- the fulfillment of Bahram Modi’s

financial success and romantic liaison with Chi-mei, and his eventual downfall.

While the history of the Opium Wars has been written and will be undertaken in

future, the novel succeeds in depicting the unremarkable lives of people like

Bahram caught in the vortex of historical events. It is Ghosh’s unerring human

empathy that makes the novel a worthwhile read.

Mosarrap Hossain Khan is a doctoral candidate

in the Department of English, New York University. He researches in the area of

Muslim everyday life in the Indian sub-continent.

Comments