In

1968, Sen. Daniel Inouye of Hawaii gave the keynote address at the Democratic

National Convention in Chicago. Standing outside Chi-town’s International

Amphitheatre that weekend were thousands of young anti-Vietnam protesters, many

being beaten and arrested by the Chicago Police for “inciting to riot.”

While

other public officials at the convention looked to shift focus away from the

civil unrest and war controversy that was going on outside, Senator Inouye had

other plans.

“The Vietnam war is immoral,” he

said. “… [But] I doubt we can blame all

the troubles of our times on Vietnam.”

That was Senator Inouye, a

no-nonsense straight shooter who was never afraid to speak the truth as he saw

it.

An American

Hero

The son of Japanese immigrants,

Inouye was born in Honolulu on September 7, 1924. As a teenager, he was a medical volunteer

during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Following the attack, over 127,000 Japanese

Americans were transported to internment camps and imprisoned due to their

ancestry. The military would not enlist

Japanese Americans for the war.

Inouye would petition the US

government for the right to serve, and when the army dropped its enlistment ban

on Japanese Americans in 1943, he volunteered for the all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat team.

Speaking about his motivations for

joining the Army, Inouye said in a PBS interview, “I wanted to be able to

demonstrate, not only to my government, but to my neighbors, that I was a good

American.”

Inouye would go on to serve his

country honorably, losing an arm and getting shot several times while trying to

advance his company to safety in a battle near San Terenzo, Italy.

Fifty-five years after his sacrifice,

President Bill Clinton awarded Inouye with the Congressional Medal of Honor.

After the war, Inouye went back to college and earned a law degree

from George Washington University. In

1959, Hawaii was granted statehood, and he was elected as its first member of

Congress. In 1962, he was elected to the

Senate, replacing fellow Democrat Oren E. Long.

Hawaii’s Champion

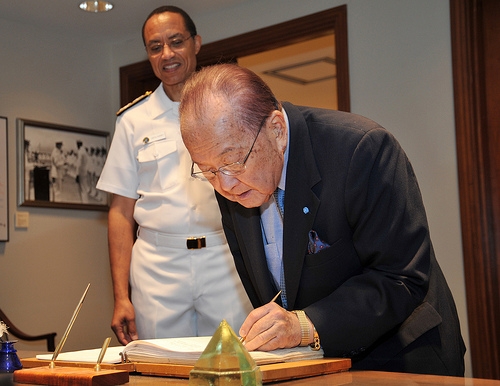

image via Hawaii Air National Guard

Inouye never shied away from giving

Hawaii political advantages on the Hill. In a brief interview with me several months before his passing, Inouye talked

about his support of filibusters, an unpopular political tactic currently used by

Republicans to prevent the vote on a measure.

“As someone representing a small

state, it was a tool used to ensure we were not pushed aside,” he said.

He proclaimed himself, “the No. 1 earmarks guy

in the US Congress,” during his tenure as representative of Hawaii’s “at-large”

district.

As a Senator, Inouye would bring

millions of dollars to Hawaii. From 2009

to 2010 alone, he sponsored close to 137 solo earmarks, totaling over $425

million. Although the tactic was seen negatively by his

colleagues, Inouye was always unapologetic about bringing money home to his

constituents.

“I would hope I know more about

Maui’s problems than my good friend the President or any of his Cabinet members,”

he said in an interview with Maui News earlier this year.

An Advocate

for the Disenfranchised

After he came back from his WWII

service, a young Inouye was once told by a barber, “We don’t serve Japs here.”

As a person of color, Inouye lived

in an America where segregation was still alive and well, and racial slurs occurred

daily. Inouye’s experience as a

disenfranchised citizen inspired his policies and stances. As a public servant, he confronted the

established order on behalf of the marginalized.

During the early debates over

segregation in the south, Inouye was one of the only senators on the right side

of those debates, pushing vehemently to end segregation in all parts of the

country.

Inouye was one of the last sitting

senators who helped pass not only the Civil Rights Act, but the Voting Rights

Act, which changed the minimum voting age to 18.

As an honored military veteran,

Inouye boldly took a stance to secure free speech for citizens who felt the

need to burn the flag in protest. The ACLU

called his position “particularly meaningful to the defense of free speech

because of his military service.”

Inouye rejected the Defense of Marriage Act in

the 1990s and was a staunch supporter for marriage equality. On the senate floor he once asked his fellow

colleagues, “How can we call ourselves the land of the free, if we do not

permit people who love one another to get married?”

Vice President Joe Biden said of

Inouye after his death, “To his dying day, he fought for a new era of politics

where all men and women are treated with equality.”

His Life Remembered

“After all these years, racism is

alive and doing well,” Inouye said in 2008, even after Barack Obama received

the Democratic nomination for president.

That

was Daniel Inouye.

He

was always pushing us further, to understand the truth of who we are as a society,

always looking toward the future.

Yet

for many outside his inner circle and native Hawaii, it could be hard to relate

to him..

It

could be hard to relate to a young man who left high school to join the Red

Cross, helping wounded soldiers during one of our nation’s most pivotal

disasters. Or to a teenage boy, who was seen as an alien in his own country, who

still fought honorably for that country, despite its faults. It could be hard to relate to a wounded soldier

who attacked three machine gun nests by himself in order to save his squad, and

still lived to tell the story. And few

have lived the life of someone who has dedicated 55 years of his life to serve

all Americans.

It

could be hard to relate to a man like Daniel Inouye, because he was as

exceptional as they come. His courage

surpassed comprehension, and his accomplishments now belong to the ages.

“Aloha,”

great Senator Inouye, you are Hawaii’s own true son.

Comments