Photographs that would typically gather dust in an old family

album take on new meaning in Eric L. Muller’s compilation of Kodachrome

photography by Bill Manbo, Colors of

Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in

World War II. The 65 colorful images fill a gap in the photo albums of over

110,000 people, two-thirds of them American citizens, who were ripped from

their homes and stripped of their property following the Japanese attack on

Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

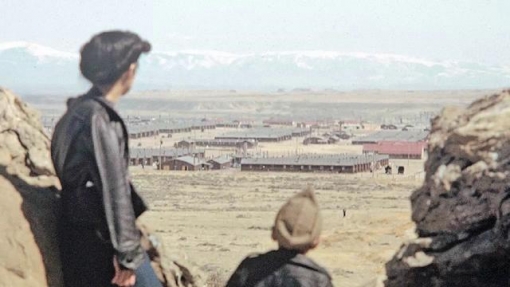

Though the Japanese American internment experience has been

represented by more distinguished photographers (Ansel Adams, for starters),

not many capture the internee perspective -- let alone in such striking color.

Kodachrome technology was just seven years old when Manbo used his 35mm camera

and homemade tripod to document his family’s experience at the Heart Mountain

Relocation Center in Wyoming.

One of Manbo’s recurring subjects was his then three-year-old

son, Billy. In an iconic image, the child grasps a barbed wire fence and stares

into the distance as a row of barracks disappears into the horizon behind him.

From cover to cover, Billy is seen enjoying ordinary childhood activities -- ice

skating, toy car racing, and climbing -- in front of an extraordinary

backdrop of barracks, guard towers, and Midwestern desert. Manbo’s photographs

juxtapose the everyday and the exceptional, and capture many seemingly

incongruent aspects of the internment experience.

In another portrait of Billy, the child stands between barracks

modeling a miniaturized military uniform. He seems to be smiling with pride,

but his father likely had more dissonant thoughts from behind the camera.

Muller reminds us that Manbo -- and his fellow internees over the age of

sixteen -- were forced to complete a questionnaire to confirm their allegiance

to the US Army and disloyalty to Japan. Those who proved loyal were often

drafted, while those who failed were sent to a harsher segregation facility.

Manbo answered ambivalently, likely confused by questions that he could not

answer freely without risking his very freedom.

With this context in mind, the irony begins to seep through

Manbo’s photographs, like those of his young son dressed in American military

garb beside the confining barracks to which he was relegated. Muller has

compiled scholarly and personal essays that contextualize the rare photographs,

unearthing latent meaning behind them and encouraging a deeper look.

Bacon Sakatani, whose childhood memories of Heart Mountain

mirror Manbo’s photographs, recalls the dissonant feeling of being “a defeated

enemy in my own country.” He remembers trips to nearby Yellowstone National

Park, like the one captured in Manbo’s image of Billy and himself posing in

front of the Grand Canyon. It looks like an average American vacation, but

Sakatani recalls the camp authorities’ allowance of such trips to encourage

“exposure to the ‘American way of life.’” Apparently, the government had begun

to fear the effects of the very segregation it had imposed.

Though the government struggled to understand the Japanese

American identity, Manbo’s snapshots illustrate the internees’ affirmation of

their multiculturalism. Orange, blue and purple kimonos mimic the moves of Bon

Odori dancers as they encircle the yagura,

a wooden scaffold constructed by the internees specifically for the

summertime Buddhist festival commemorating their Japanese ancestors. On the

opposite page, a Heart Mountain Boy Scout troop marches with the American flag,

flanked by the local bugle corp during a community parade. The complementary

images of sumo wrestling, Japan’s national sport, and baseball games, the

quintessential American pastime, reveal the dual identity embraced by the

internees.

Given the misunderstood identity of Japanese Americans at the

time, Manbo’s photography represents more than just a hobby. “Photography

became a representational battleground,” writes Jasmine Alinder in her essay, Camera In Camp. She reminds us that

cameras were considered contraband in many camps, effectively stripping

internees of their right to representation in addition to the constitutional

rights they had lost. But the complex experience of being American by birth,

Japanese by ancestry, and unwelcome in one’s own country was something that

outside photographers (Ansel Adams, among others) could not capture with the

same understanding and familiarity of a father recording his family’s reality.

As a fourth generation Japanese American (or Yonsei) myself, I have heard family

stories of internment that personalized the details I had learned through books

and history classes. But it was not until seeing Manbo’s collection that I

perceived my grandparents’ stories as more than distant memories. Muller

recognized this power of color photography to revive the past and has created a

book that presents the internee experience through a modern lens.

Just as Manbo’s slides were miraculously preserved (in a box in

his son’s garage), Muller’s compilation will help preserve our collective

memory of the internment experience. It is only reasonable to expect that as

the WWII generation passes, more images like those of Manbo will surface,

bringing new life to our history even as it falls further into the past.

Sachi currently lives, works, and plays in San Francisco. She’s

a paralegal by day, an athlete/filmmaker/foodie by night, and a writer by

fancy.

Comments