By Jason Coe

From the outset, Life of Pi, Ang Lee’s latest Oscar contender, promises a story that will make us believe in God. Although Lee’s adaptation of Yann Martel’s 2002 Booker Award-winning novel may not fill church pews, it certainly affirms the miracles of CGI. The animals look very real, obfuscating the already-blurry line between fantasy and reality that emblematizes the narrative. Reviewers often discuss the film’s spiritual themes and impressive visual effects, but Lee’s interpretation is also topical to our present political climate. Despite its theological aspirations, the story of Pi has more to do with the challenges of immigration than divinity.

The story begins when Pi must leave behind the paradise of his family-owned zoo in French colonial India for Montreal and “a better life.” After the freighter carrying his family and the zoo inmates capsizes off the coast of Australia, Pi must share a lifeboat with survivors including a zebra, a hyena, an orangutan, and most impressive of all, a “man-eating” Bengal tiger named Richard Parker. Together, Pi and Parker battle biblical tempests, the ravenous hyena, a carnivorous floating island, and a glow-in-the-dark humpback whale, eventually touching down on terra firma without Parker's having eaten Pi.

However, this idyllic and touching story of immigrant hardship and success has a catch. When a pair of insurance investigators interview Pi, they refuse to believe Pi’s fantastical narrative, insisting upon a less ridiculous story. Pi then reveals that there are two versions of his narrative: in the first, Pi and Parker reach the shores of Mexico through sheer ingenuity, luck, and human fortitude; in the second, there are no animals, and Pi survives by cannibalizing the other humans in the life boat, including a Taiwanese sailor, a chef, and his own mother. In both stories, Pi suffers, his family dies, and the ship sinks, but the remaining details are impossible to confirm, as Pi is the lone survivor. “So, which story do you prefer?” Pi asks the investigators. As the audience, we prefer the one with the tiger, but why?

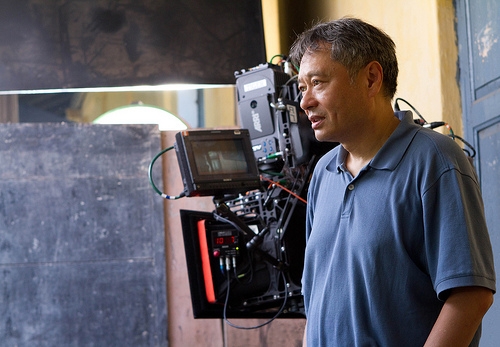

Stories of immigrant success are essential to the American historical psyche, inspiring millions to leave their ancestral homelands for a shot at the American Dream. Life of Pi is a film about someone who makes it -- while making plain that some did not. Pi’s success where others failed mirrors the unlikely rise of the film’s director. Ang Lee is by far the most successful Asian director to cross over into Hollywood. His triumphs at the American box office and on awards night eclipse even the world’s most famous Lee, who left Hollywood for Hong Kong because his potent fists and star power could not break through the bamboo ceiling. Director Lee managed a relatively smooth transition from Taiwan’s tiny and underfunded film industry to Hollywood’s blockbuster productions, but his work consistently speaks to the difficulties of hybrid identities and cross-generational conflicts endemic to diaspora. With Life of Pi, Lee again finds room for scenes that are most telling of the immigration experience.

In one such scene aboard the ill-fated freighter, Pi’s mother politely asks the French cook for a vegetarian option. She receives a racist reply and an argument ensues between the chef and Pi’s father, who transitions from English to French with ease and eloquence. He berates the chef, stating, “You can’t speak to her that way. You’re just a cook!” But despite being merchant class and Western-educated, Pi and his family must face the reality of migration to the West: even uneducated lower-class whites are entitled to abuse them. A Taiwanese crewmember and self-described “happy Buddhist” discloses that he flavors his white rice with tiny amounts of meat gravy to get through the long voyage. Pi’s family declines to do the same, but this scene foreshadows the impending moral concessions Pi must make in order to survive his journey to the New World.

Pi’s willingness to “be a tiger” represents the darker side of the immigrant success story. Not everyone has the economic and political privileges afforded to Pi and Lee. Pi survives not through idealized heroics but through ruthlessness and skills acquired through his colonial background such as swimming and English literacy. Similarly, before trumpeting Asian Americans and Canadians as a model minority, we must consider what factors are actually in play and who is excluded by such a false generalization. The model minority myth is not victimless and often overshadows the underprivileged majority of immigrants who arrive on American shores without recourse and scant opportunity. Or to globalize this allegory further, perhaps the “miracle” of late 20th century economic success in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan is less a function of “tiger economies” and more a result of favorable political alliances and foreign aid from the United States -- at the expense of neighbors sealed behind the Iron Curtain.

Though they cloud the truth, enchanting and explanatory narratives of cultural essentialism or exotic cats are far more palatable than those of lost humanity and cannibalism. This particular use of magical narrative to disguise or allegorize traumatic experience has roots in the literature of the Jewish diaspora. Martel was inspired by Max and the Cats, by Brazilian Jewish émigré Moacyr Jaime Scliar, in which an escapee from Nazi Germany is stranded on a lifeboat with a jaguar. Similar fantastical trauma narratives include the graphic novel Maus and the animated film An American Tail, in which anthropomorphic mice representing Jewish migrants are on the run from evil cats standing in for Nazis and anti-Semitic groups. Like Pi’s story of the tiger, these narratives do not ease the unspeakable atrocities committed, but rather present the experiences in a more digestible format from which we can more easily extract meaning from the traumatic events.

In addition, these narratives imply an element of survivor guilt. Famed intellectual and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl once stated, “We who have come back, we know -- the best of us did not return.” Pi too admits as much: “[The cook] was such an evil man,” but “worse still, he met evil in me -- selfishness, anger, ruthlessness. I must live with that.” It’s no coincidence that the Buddhist sailor and Pi’s mother do not survive; the zebra is weak and the orangutan too human. Pi knows the truth of his own depravity but ultimately prefers to tell the story with the tiger. We too can be partial to a more enchanting narrative that camouflages our pain, while acknowledging the privilege of surviving when others did not.

Jason Coe, a former Hyphen film editor, is a graduate student at the University of Hong Kong, primarily researching Taiwanese and Asian American cinema.

Comments