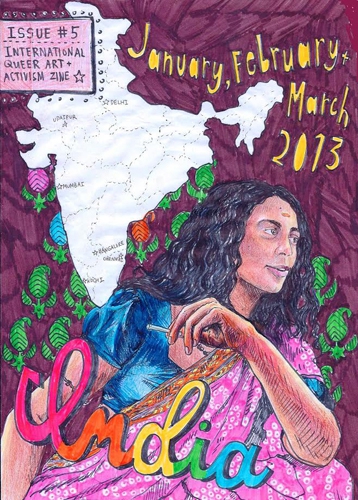

After graduating from college in 2012, I spent the next fourteen months traveling to fifteen countries in search of queer artist and activist communities. From the outset, I planned to create zines in order to highlight the individuals and organizations I encountered.

But how did I go from being a recent college graduate with hardly any savings to traveling the world?

In my last year at school, my proposal for an international queer art and activism zine project was accepted by the Watson Foundation. As a Watson fellow, my wandering nomadism was funded by a foundation, elevating whatever I did into something prestigious. This was a privilege that gave me a strong feeling of legitimacy and security on my travels. My lack of a home base was the very point of the project, and the fellowship money and mandatory travel insurance made me feel as though I was playing the Game of Life and with Monopoly money.

*

In 14 months, I visited Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, India, South Korea, Japan, Turkey, Germany, and The Netherlands. Some countries were chosen because I had a lead that I wanted to pursue, others fell into place through community I developed, or when I was in route from one place to the next. A few were brief visits, while others I stayed for 2-3 months. In all of these places, I was interested in learning about the implications of being “visibly” queer in different contexts, and how artistic expression was enhanced or altered by the social and political factors and the historical traditions of a country. In each country, I hoped to learn about the intersections of class, gender, racial, ethnic, and cultural identities.

Last March, I spent time an artists’ collective gallery space called Backyard Civilization located in Kochi, Kerala in southern India. It deviated from my preconceived ideas of what a queer community looked like which included queer bookstores, discussion groups, parties etc. Backyard Civilization is a hotbed for young Indian artists of all genders who live and collaborate together in film, writing, painting, performance and sound art, despite the pressure to marry and work 9-5 jobs. There were a few who identified as queer, but the community included straight Keralan men who enjoyed reading Judith Butler (more on this in a second).

At Backyard Civilization, I became close with a well-known Malayali poet and cultural commentator, Latheesh Mohan. One day we were sitting on thin bamboo mats in the small room adjacent to the homemade outdoor kitchen that smelled of amazing coconut oil, which we put in all of our meals. There was one small fan, which gave us some respite from the relentless mosquitoes, and a couple of local Malayali newspapers strewn across the floor

Latheesh and I meandered through a bevy of topics that muggy afternoon. I remember asking him specifically why there were so many straight and cisgendered Keralan men interested in queer and feminist theory. He explained the age-old inclination of Malayali men to participate in the larger ‘debate’ of his time. Thus the interest in queer and feminist theory could be seen as an interest in taking part in another discussion fashionable on an international level. Since then, Keralan men in universities had naturally taken to reading Sedgwick, Halbsterstram, Butler, and other academic theorists. When I checked in with Latheesh the other day to have him look over what I had written about our conversation, he emphasized the complexity of the dynamics at play and that this was just his read on the trend. However, the stark contrast between meeting straight Keralan men who quoted Butler, with the many queer and trans-identified Keralans who have left their state due to the extreme homo/transphobia is one of the many types of subtle and location-specific nuances that I learned about.

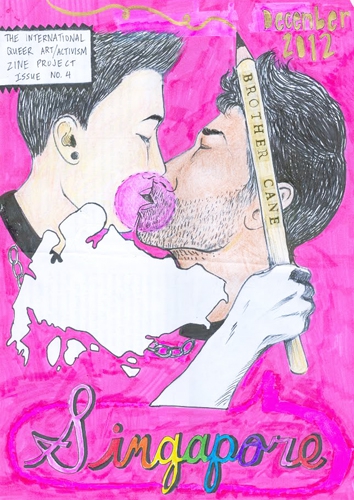

In Singapore, the government uses monetary fines and obnoxious bureaucracy to censor artistic representations of queer or sexually explicit content. For example, independent art and music venues are required to pay a large deposit to government officials, and the minute someone under the age of 21 enters, the deposit is taken away, putting the venues in danger of bankruptcy. Artist, Loo Zihan addressed this practice in his art show Archiving Cane at a downtown gallery, the Substation. He photocopied the IDs of every visitor and displayed them alongside required state permits. During his performance he walked outside to light a cigarette, stating that according to the law he needed to be 10 meters away from public buildings to smoke. His script had been approved by the government in advance and rehearsed so many times that much of the audience criticized the text as boring and lifeless.This was the exact point Loo wanted to get across. Without spontaneity, the quality and stimulation of art, dies.

Loo’s piece was actually an effort to bring back a performance from 1993 by a gay performance artist, Josef Ng, whose piece “Brother Cane” resulted in a public debate over obscenity in performance art and a subsequent ten-year restriction of the licensing and funding of performance art in Singapore. During that period, Singaporean playwright Tan Tarn How wrote:

"If society is a tree, and its fringes are the leaves at the tree's outermost reaches, then trimming the fringe, where the youngest, tenderest leaves grow nearest to the light, can only stunt the growth of the centre. That is how you get the little bonsai plants, pretty but poor imitations of the real thing."

Although such outright censorship is much less likely to happen today in Singapore, How’s commentary poignantly describes the ways in which even small concessions to the state in the art world cause harm to the foundation of a society.

I wore different hats, that of the performer, facilitator, collaborator, listener, general participant, and even barber, while interacting with a wide variety of queer communities. These role changes were meant to minimize my intrusion while fostering productive collaboration and meaningful connections, with the inevitable moments of tension and overstepping of boundaries. Unsurprisingly, making embarrassing mistakes was crucial in challenging my assumptions, improving my project and how I interact with communities now.

After seeing queer and trans artists and activists around the world weave their varied narratives into existence,I know that what our communities need isn’t our worries about legitimacy and institutionalization. It’s about coming together and shaping the media and culture so that we represent the margins in ways that are authentic and visible. t’s about making sure we leave room for healing justice, food justice, and all transformative justice. The rest will follow suit.

P.S. In this upcoming series, I hope to explore how shared experiences and identities of queerness cross cultural and linguistic lines, and how we organize or exist in the U.S. compares to queer communities in the countries I visited while abroad. If you’re particularly interested in hearing more about one, or more, of the countries I listed, send me an email: heymiyuki (at) gmail (dot) com

***

Miyuki Baker is a freelance artist, journalist, organizer, performer, barber, translator,

and healer residing in the place where circles overlap. After graduating from Swarthmore College in 2012, she traveled around the world for 14 months on a Watson Fellowship to perform and make zines about international queer art and activism.

She is the founder and director of Queer Scribe Productions and Asian, Gay and Proud, both of which aim to bring visibility to marginalized stories. Miyuki is also passionate about chronicling life through illustrations, and urges you to visit and subscribe to her weekly updated illustrated blog.

Comments