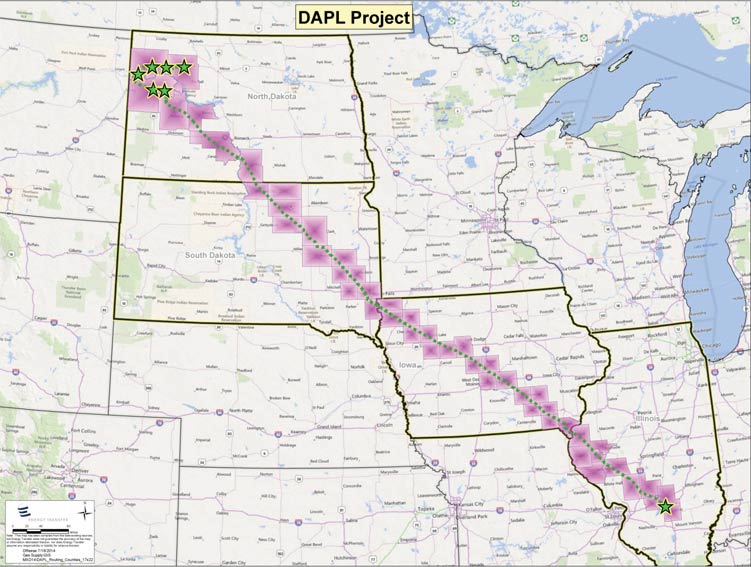

What is going on at Standing Rock right now is historic, and if you need a moment to catch up, here’s your chance. Not unlike the Keystone XL proposal, The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) is comparable in length, and would begin at the border of Eastern Montana, cutting through North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Illinois. If built, the pipeline will transport up to 570,000 barrels of crude oil daily. For the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe this is simply the latest slight against tribal lands and the people who inhabit them. Current laws prohibit the tribe from doing little more than assessing the safety of construction and having a cultural dialogue around the effects of a project this massive. At this point, dialogue is useless when construction is already underway. This $3.8 billion project is the government’s decision to further assert its power over Native lands and is sure to damage the community during its construction and onward. The United States has had a horrible track record with tribal nations. Between 1779 and 1871, the US entered over 500 treaties with Native American tribes, all of which have been broken or nullified. One of the largest acts of abuse was the Dawes Act, which allowed the federal government to divide land for Westward expansion and began a period of forced assimilation by turning Native Americans into subsistence farmers and removing tribal governments. The consequences of this act carried on into the 1970s during the Boarding School Era, where Native American children were taken from their families, made to cut their hair, change their names, and relinquish their language and traditions, often while facing physical and sexual abuse. Today, the Bakken oil boom has turned Montana and North Dakota into areas of economic prosperity, promising employment and opportunity to laborers from out of state. However, it is also one of the latest offenses, as the consequences of the boom have negatively impacted the surrounding tribes. It has invited the setup of what people have colloquially called “man camps,” or work sites for drilling that are largely inhabited by men. It is in these areas where a high number of sex crimes take place, especially against Native women and girls. When Native women are subject to these crimes, there is little faith in seeking justice. Native women are murdered at more than 10 times the national average, and neither federal government nor local law enforcement have acted to investigate or even track the many murders and disappearances.

The greatest concern is that the pipeline will affect the drinking water as it runs under the Missouri River. This concern isn’t unfounded; pipelines leak all the time. In 2016 alone, the US experienced 15 pipeline accidents, including the Shell Oil leak in Tracy, California, which let 21,000 barrels of crude into the soil. Shell waited three days to report the spill, the line’s second rupture in 8 months, at which point there began a hefty cleanup, moving over 6,500 tons of polluted soil to a nearby landfill. California’s Central Valley is another area largely inhabited by migrant workers who work on farms where 8% of the nation’s agriculture is grown, and investigations are still in progress. When it comes to pipeline accidents, it is not a question of if, but a question of where and when. The quality of the Missouri River is critical to the health and economic well being of the tribe. One cannot help but think of the crisis in Flint, Michigan, where families are now struggling with lack of filters, the high cost of bottled water, dangerous levels of lead exposure over the course of years, no mobility for evacuation, and little support from local and state government. While witnessing Flint, we now have the opportunity to better understand and even address the Standing Rock Sioux’s concern over a vital resource—water.

At least 30 tribes have come together over this issue, setting aside many years of conflicts. In addition, Black Lives Matter has shown up to protest with them in solidarity. Black Lives Matter organizer Miski Noor commented in Truthout:

“As Black Lives Matter, we have built power and we have a platform. And as a movement, we have a duty to uplift and amplify the stories and struggles of all marginalized folks, as our liberation is intertwined.”

Asian Americans, especially young activists, have taken to working in solidarity with Black Lives Matter. We have no hesitation to say that Black folks are our friends, teachers, mentors, coworkers, neighbors—it is easier for us to extend our empathy and work within communities we inhabit. However, as a political community, we have been largely quiet on the matter of #NoDAPL. For as many articles, open letters, and organizations that voice support of Black Lives Matter, few to none can be found in support of #NoDAPL. This may be due to the fact that Cannon Ball, North Dakota is miles away from many of our communities, which tend to be urban and coastal. The topographic distance perhaps extends to mental and emotional distance—but this is no excuse. Black Lives Matter was quick to respond, and so must we be.

It is a running joke that high school graduates claim Native identity on their college applications to reap the financial “benefits” that Native Americans purportedly receive. Living in Montana, I hear insensitive remarks all the time about Native Americans living off government assistance. For Asian Americans, the model minority myth comes with perceptions that that obscure our oppressions. A hard look at our communities shows how we still struggle: we face rapidly increasing evictions from gentrification, immigration laws which harm undocumented families, voter suppression, trafficking, and the exploitation of migrant workers. For Native Americans, many tribes suffer from high mortality rates, unemployment as high as 95%, and with more than 80% of people living below the federal poverty line. Racial profiling, sexual assault, trafficking, and lack of access to adequate healthcare is common among marginalized communities. The truth is that the challenges faced by Standing Rock and communities like it are not so different from ones we know to exist in ethnically diverse cities all over the US. We are now witnessing a continuation of this shameful history. However, it’s not the only history we need to consider.

It is easy to succumb to the desire to focus on our own communities, our own challenges. Among marginalized groups, anxieties crop up about resource scarcity, the feeling that certain groups will be advocated and provided for, while others will not be. This makes us less willing to throw our support behind other groups who may be struggling. Asian Americans worry about being forgotten, a side effect of listing ourselves as “other” in official documents. To echo Miski Noor, our labor, our histories, and our freedom are connected, and therefore we have a responsibility to uplift one another. Hyphen has compiled rich histories and key figures of Asian American solidarity, a tradition which younger generations of Asian American activists are boldly carrying on. In this case, we must put our money where our mouth is if we are to continue this radical tradition of solidarity work. Asian Americans are the fastest growing minority in the US, and when possible, we have the power to rally our communities in numbers, instead of taking comfort in them.

So what can we do?

- Protesters at Standing Rock are in need of supplies, including pots, pans, utensils, blankets, non-perishable food, tents, batteries, and drinking water. You can find an entire list of needs here. Supplies may be sent to the following address:

Bldg #1, N. Standing Rock Ave

PO Box D

Fort Yates ND, 58538

- You can also donate to the DAPL Fund on their site to help with supplies and legal defense.

- You may also adapt the sample letter here for the use of your organization to support the efforts of #NoDAPL and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

- Call North Dakota governor Jack Dalrymple at (701) 328-2200. You can leave a message stating your thoughts.

- Call the White House at (202) 465-1414.

- Sign the petition to the White House to stop the DAPL.

- Lastly, do not let news of this be drowned out by the theater of national politics. Regardless of who is elected, this $3.8 billion project will want to advance.

Comments