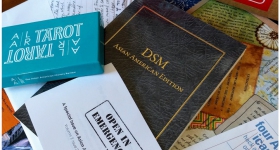

For December, we bring you this poem about a young woman caught between the bloody edicts of the Cultural Revolution and the transcripted words of Western novels.

—Karissa Chen, Senior Literature Editor

Everything Where It Belongs

How many nights Mei Hsin read of fallen women,

transcribed in her own hand. Pored by lantern light,

one arm an Ionic column, and the rest of her, drapery,

gliding down to inspect the broadsides she’d spent

weeks repurposing. Before coming to Wuping, she had,

with her mother’s sable brush, obscured the printed words.

To build a new world we must break the old one gave way

to In the afternoon rush of the Grand Central Station.

To avoid disgrace, long live the red terror faded under

His eyes had been refreshed by the sight of Lily Bart.

Ink to ink; edict to narrative. She worked

with an increasingly sure, swift hand. Whole scenes.

Whole chapters of Wharton, Flaubert, Tolstoy in translation.

Tedious, at first, until she noticed how 火車 suddenly

appeared to her like the starburst of a bullet pock,

or that the puny figure within 開 was not only

standing at the gate, ready to depart, but also

looking back. Each slender frieze of writing became

its own missive, one that over and over told her everything

was where it belonged. In Wuping, when the moon set,

she folded these well-read pages to firm squares and slipped

them back between bedsheets, though the village

Red Guard were as young as she, and months ago

befriended. She hadn’t known what to fear besides

beatings. One was selective about such things.

Fear was a tightening ribbon, bounding out family, city,

nation. How could anyone think clearly about nation

then. Fear was the fifth chamber to her heart.

Perhaps her clearest understanding of anything.

On dawns yielding fleas that scorched her left arm

and right leg, she arrived to the pen to teach children

their letters and found she had nothing to say, nothing

to dictate, not even curses. She’d recall the night before,

how she posed for the bluebloods of Fifth Avenue, New York:

The unanimous “Oh!” of the spectators was a tribute

to the flesh-and-blood loveliness of Mei Hsin.

Never mind Lily Bart. Never mind Edith Wharton.

What use was Wharton when Mei Hsin was prima donna

of these passages? Never mind the broken bodies

that concluded all these novels. Almost a pleasure

to jettison that. But a pleasure to read and, later,

recall the crispness of poplin against bare skin, as if

it were her own memory. It had become her memory.

Was anyone so lucky, in defiance of space and time,

to be a Lily, Anna, Emma, when Mei Hsin was a forced

laborer in one of many waves of the Cultural Revolution?

Decades later her daughter will read these novels

almost by accident. Will learn what no one else had.

That what began as transcription became, climbing out

of that sable brush, sister-selves. Their lives her lives.

The daughter will have already known which aunts

vanished, which uncles starved; will have heard the polite

prose of desperation. Dear one, sending us twenty dollars

is a little better than sending ten. There will be hearsay.

There will be no documents but the novels themselves.

***

Mori Walts is a queer Nikkei multimedia artist based out of Santa Rosa CA who is currently focusing their art on processing the imaginary Japan within the western imagination. They hope to pursue a career in animation.

Comments