Jee Leong Koh is the author of Bite Harder: Open Letters and Close Readings, forthcoming from Ethos Books in Singapore this year, and of Steep Tea (Carcanet, 2015), named a best book of the year by U.K.'s Financial Times and a finalist by Lambda Literary. He has published three other books of poems and a book of zuihitsu. His work has been translated into Japanese, Chinese, Malay, Vietnamese, Russian and Latvian. Originally from Singapore, he lives in New York City, where he heads the literary non-profit Singapore Unbound and publishes authors of Asian heritage under the imprint Gaudy Boy.

Tammy Ho Lai-Ming and Jason Eng Hun Lee: How many years have you been writing poetry?

Jee Leong Koh: More than 35 years. I started writing poetry when I was in primary school.

THL & JEHL: Do you remember what inspired you to write your first poems?

JLK: Rain. Reading literature at school. Discovering an anthology of poems in a home that does not have a love of books. Wanting to give a beloved teacher a gift of handwritten poems.

THL & JEHL: Can you list some important moments in your early experiences as a poet?

JLK: Getting a check in the mail for a poem that was read over national radio. The poem described rain lashing the bronzed back of the ground. From the first, I was invested in the pleasures and pain of a poetics of embodiment. Another important moment was my discovery of, first, Boey Kim Cheng, and then, Cyril Wong, in the Singapore literature shelf of local bookstores. Kim Cheng showed me that a persuasive and passionate contemporary poetry can be written by a Singaporean near my age. Cyril gave me the courage to write frankly about family and sex.

THL & JEHL: In your opinion, how useful is poetry as a medium for expressing your personal experiences? How does it compare to the other genres you write in?

JLK: I go to poetry to find out what I think and to express how I feel. Writing prose is a responsibility, but writing poetry is a joy. It feels as good as an orgasm and it lasts longer. There is total absorption and loss of self to the writing of a poem.

THL & JEHL: What is your educational background and current occupation?

JLK: I went to primary and secondary schools and junior college in Singapore. I read English as a undergraduate at Oxford University, U.K., on a government scholarship. I received my postgraduate diploma in Education from the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, in Singapore. I taught public school in Singapore for eight years, becoming the head of the English department and vice-principal in the process. Then I moved to New York, where I completed a Master of Fine Arts (Creative Writing) at Sarah Lawrence College. Now I teach English at a private school in NYC.

THL & JEHL: What influence, if any, do they have on your writing as a poet?

JLK: My British-based and British education has grounded my writing on British literature. The sonnets in my first book, Payday Loans, are influenced by Shakespeare. My second book, Equal to the Earth, owed a great deal to Keats, as one reviewer observed.

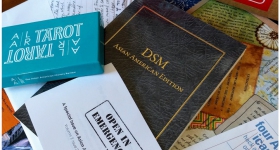

The diversity of poetic traditions in the United States has led me to study Asian American literature and, in particular, Japanese literature. A poetry workshop with Japanese American poet Kimiko Hahn opened my eyes to the possibilities in Japanese poetic forms. After that workshop, I wrote my book of zuihitsu titled The Pillow Book. My next book, Steep Tea, takes its title from a kasen renga. I’m working right now on a book of haiku.

Living away from home has also deepened my interest in Singapore literature, especially the writings of Singaporeans, such as Goh Poh Seng and Justin Chin, who also moved away from Singapore to North America.

THL & JEHL: Does your poetry mention or include other cultural or linguistic markers? What purpose do they serve in your writing?

JLK: No, I think and write solely in English. I have referred to Chinese and Singaporean history, culture and literature in my writing but I don’t set out to write about these topics directly. It’s impossible for me to generalize about what purpose these references serve in my writing. It is different in different poems. I don’t have an agenda or manifesto in my use of my cultures. I use such references to think with and around.

THL & JEHL: What aesthetic or poetic style would you say best characterizes your work?

JLK: Lyrical, with a concern for poetic form, and a penchant for literary masks and poetic sequences. My first book, Payday Loans, is a sequence of 30 sonnets, titled after each day of the month of April. My second book, Equal to the Earth, opens with “Hungry Ghosts,” a sequence of persona poems based on queer figures in Chinese history. My third book, Seven Studies for a Self Portrait, is made up of seven poetic sequences, each showing a different facet of self-investigation. My fourth book, The Pillow Book, is a collection of zuihitsu, the Japanese essayistic form. The poems of my fifth book, Steep Tea, respond to women’s poetry from across the world.

THL & JEHL: Who would you cite as your main literary influences?

JLK: I am very influenced by Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Keats, W.B. Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Stevie Smith and Philip Larkin. Having migrated from Singapore to the United States, I feel close to W.H. Auden and Thom Gunn, both of whom moved from the UK to the USA and both of whom were gay too. I’m absorbing much from American literature, from admired authors such as Thoreau, Melville and Roberto Bolaño. From Singapore, Boey Kim Cheng and Cyril Wong are my main influences.

THL & JEHL: How many years in total have you spent in Singapore? How many years have you spent outside it?

JLK: I lived in Singapore for 33 years and have lived in New York City for 15 years. I visit Singapore every summer for 2-5 weeks.

THL & JEHL: How often do you write about Singapore? Does living outside of it affect how you represent it in your writing?

JLK: I don’t currently live in Singapore. I write about it all the time. It is in all my books of poetry and prose. The idea of home is a major preoccupation of my writing. Living in New York has given me another pair of eyes on my home city. As a gay man, I see the lack of equality in Singapore. As a writer, I see the lack of freedom. Living outside my home city has given me a critical perspective on it that I would never have had if I had stayed.

THL & JEHL: Have you always lived in a city? Do you find living in a city nurturing of or stifling to your creativity?

JLK: I have always lived in a city and I cannot imagine doing otherwise. The city is a supreme cultural achievement of humankind. The technological, spatial and social innovations that brought the city into being are tremendously inspiring. The diversity of people and activities is stimulating. The city provides the best image for our attempt to get along despite our differences. It provides both fame and anonymity. It is both constant and changing. It has its natives and its foreigners. My work is deeply in debt to the city.

THL & JEHL: How do you think a city is best narrated?

JLK: Different ways of describing the city brings out different aspects of the city. In a novel about a city, such as Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, the city can be more than a setting for the action; it becomes a character in its own right. Because a novel has to work with plot and characters, it shows best the city as a place of organic development and unified diversity. Lyric poetry about the city emphasizes a deep individual response to the city: it seeks originality and intensity rather than persuasiveness and completeness. Poetic sequences can best convey the disparate and fragmented experience of the city. It can also provide multiple perspectives, not seen through the eyes of different characters as in the novel, but at different times and in different moods.

THL & JEHL: Do you consider yourself well positioned to contribute to the narratives of Singapore?

JLK: I think we need many different narratives of a city. My narrative is from the point of view of a dominant gender, a racial majority, a highly educated class, a sexual minority and a voluntary exile. The first three categories apply to many Singaporean poets writing now. The last two, especially the last, distinguish my perspective from theirs. For instance, my poem “To A Young Poet” advises the addressee to “quit the country soon as you can.”

JLK: I’m lucky that the younger poets and critics in Singapore welcome my writings on Singapore even though I now live away from the country. For instance, the poet and critic Gwee Li Sui has written positively about my work in a number of academic articles, the latest of which is about the political dimension of contemporary Singaporean poetry. Singaporean writers are very conscious of being transnational since a prominent number were born or grew up in Malaysia, China, India or elsewhere, or their parents and grandparents did. Also, many of the most well-known poets have migrated to other countries. Besides Goh Poh Seng and Justin Chin, whom I mentioned earlier, Boey Kim Cheng migrated to Australia, although he has now moved back to Singapore. Wong May moved to Ireland. This consciousness of being transnational tempers the nationalistic sentiments that surround any project of constructing a national literature.

THL & JEHL: Is there any particular aesthetic or poetic style that you use to represent Singapore?

JLK: No, I write about Singapore in the same way that I wrote about other subjects. My style changes because of my response to the subject, but not because of the subject itself. I don’t think of poetry as being primarily mimetic. Fiction is mimetic, but poetry is expressive.

THL & JEHL: Over the years, what changes (both subtle and obvious) have you noticed in Singapore? Do you feel compelled to write about them?

JLK: A very symbolic recent event was the death of Lee Kuan Yew, the first prime minister of Singapore. To most Singaporeans, it signaled the passing of an era of heroic and optimistic nation-building after independence from the British. An anthology of poetry, A Luxury We Cannot Afford, was published after Lee’s death. I contributed a poem to it. The title of the book is an ironic allusion to Lee’s dismissal of literature in favor of practical economic development. The anthology was intended to be a riposte. The poems collected, however, convey a wide range of perspectives, not only critical ones. Still, I was struck by the fact that the editors and publisher did not dare to call Lee by his name in fear of libel laws, which Lee had often invoked against his political opponents, but called Lee "The Man" instead. I understand that the anthology was also vetted by the Attorney General’s office before publication. To my mind, this book represents the political regime with which Singaporean writers have always had to negotiate. To be blunt, it represents our lack of freedom.

Beyond the death of Lee Kuan Yew, my writing has not been motivated by particular events in Singapore, because I do not feel their immediacy. The more things change, the more they stay the same, however. The government, dominated for so long by a single political party, still practices the repression of dissent, so its narrative about Singapore is still widely embraced by the populace. To protest against inequality and censorship, I turn to prose, not poetry. I find open letters to the government and the general public easier to write and more accessible to read. I’ve written letters of protest against the National Library’s ban of three children’s books that depict non-traditional (e.g., LGBT) families; the National Arts Council’s withdrawal of a publishing grant from Sonny Liew’s graphic novel, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, for its political unorthodoxy; and against Singaporeans for re-electing the People’s Action Party with an increased percentage of popular vote, even though economic inequities and political oppression continue to grow.

THL & JEHL: Does your home city’s colonial past/history have any bearing on your writing of place?

JLK: Absolutely yes, because I write in English, the double-edged gift of the British. Equally, because the economic development of Singapore by the British brought my family here from China in search of a better life. My schooling is deeply imprinted by British culture. I think whether this colonial past is a hindrance or a help depends very much on what we make of it and how we make use of it. The strong writer makes use of it. The weak writer is used by it.

THL & JEHL: Do you think of your poems as writing against or in response to dominant Western/colonial representations of Singapore?

JLK: The West sees Singapore mainly as an economic miracle. Most recently, American newspapers have touted the Singapore health system as one that the United States could study and learn from. Or else Singapore appears in their pages as a food paradise. It’s not surprising that the West should think of Singaporeans in these ways because these ways are also how Singaporeans think of themselves. I do not write to challenge these perceptions directly, since I write out of the need for personal expression, but I certainly hope that my writings could help modify these perceptions. I would like Singapore to be seen as a creative source of imaginative literature.

THL & JEHL: Are there any other political, social or economic critiques about your home city represented in your poetry? Has this sentiment grown or been reduced over time?

JLK: By writing openly about my experiences as a gay man, I assert the vitality of the contributions of the queer writers to Singapore literature. We have important queer voices in all three main literary genres. In poetry, Arthur Yap, Cyril Wong, Yeow Kai Chai, Ng Yi-Sheng, Desmond Kon, Tania De Rozario and Alfian Sa’at. In drama, Eleanor Wong, Ovidia Yu, Haresh Sharma, Joel Tan and Alfian Sa’at again. In fiction, O Thiam Chin, Amanda Lee Koe, Jeremy Tiang, Johann S. Lee and Andrew Koh. Our rights may still be abrogated in Singapore, but our part in the national literature cannot be ignored.

I have become more interested in political change after the very disappointing 2015 election in Singapore, which returned the dominant party with an increased majority, despite the palpable need for change. The election of Donald Trump as the 45th President of the United States in 2016 is also another cause. I have participated in gay pride marches before, but the Women’s March on Washington in 2017 was my first mass protest for a broader cause. The surge in fascist power in Europe and the United States is worrying, and there are not dissimilar parallels in Singapore politics. At the same time, economic inequities are increasing around the world. Writers could do more to bring attention to these political, social and economic changes.

THL & JEHL: How do you think your writings about Singapore differ from poets of earlier/later generations? What perspectival differences do you think exist between these generations?

JLK: As Singapore poetry evolves, writers have naturally become less concerned with the anti-colonial struggle and nation building, and more concerned with the political challenges of the present time, such as racism, classism, homophobia and economic inequities. The later poets are thus sometimes seen as being more critical of Singapore. They are also more invested in the personal vein in their writing, and do not restrict themselves to “national” themes, and so we see a greater variety of subject matter and approaches in the current poetry. Because the later poets are more “individualistic,” they are also more loosely bound together in common political-aesthetic objectives. The earlier writers found it useful to see themselves as part of Commonwealth literature, a common movement to establish literary autonomy from colonialism. The later writers are more likely to think of themselves as part of World or Global literature, mainly for the purpose of advancing their literary careers.

THL & JEHL: How do you think Singapore might change in the future? Do you foresee yourself living in the city in, say, 5, 10 or 20 years’ time? What kind of changes do you think might occur within those timeframes?

JLK: The biggest change in Singapore in the last 10 years has been due to the influx of new immigrants from China, India and around the world. About 40% of the population now does not hold Singapore citizenship. The immigrants have brought with them different cultures and politics. They may see themselves as different from Singaporeans for now, but their children, born and raised in Singapore, will see themselves as Singaporeans. How these children will change Singapore’s culture, and poetry in particular, will be an interesting question. The change will be partly determined by their reception by current younger writers who will be the gatekeepers of culture by then. My hope is that they will be warmly received as they will show us new possibilities for Singapore and Singapore literature. I prefer to think of Singapore not as a bounded entity but as an unbounded network of connections across the world. So even if the children of these immigrants should choose to leave Singapore, they bring Singapore with them to wherever they reside.

THL & JEHL: What is your reaction towards the expression "the Asian experience"? Is this a meaningful idea? Have you explored notions of an Asian identity in your poetry?

JLK: I don’t think the expression “the Asian experience” is a very meaningful one. There are too many Asias for such a generalization to hold much content. Poetry deals with a specific experience, to my mind, and not with generalizations. I’ve written poems about Singapore, but not about Asia.

My poetic sequence “I Am My Names” (from Seven Studies from a Self Portrait) looks at the self through different collective lenses: as a Son, Lover, Poet, homosexual, Singaporean, Chinese and Father. Even in those poems, however, I try to catch myself in the mirrors of those categories, and do not try to generalize about what the categories mean.

THL & JEHL: How do you think Singapore differs from other Asian cities?

JLK: Singapore does not have a hinterland. The city is the country. As such, all our poetry is urban poetry.

THL & JEHL: Do you think Asian cities tend to have more similarities than differences, and if so, what are they? Do you think these similarities and differences are true of cities generally, not just Asian ones?

JLK: Asian cities are similar in so far as they share similar histories. The spread of Hinduism from India, of Buddhism from India and China, of Islam from Arabia, of Christianity from Europe, links certain Asian cities. The experience of different types of colonialism links other cities. I think the similarities between cities from all over the world are more important than their differences. For better and for worse, cities are concentrations of power — literary, political, economic — and so they are where things happen.

THL & JEHL: How do you think Singapore is perceived around the world culturally (particularly in terms of literature), socially and economically?

JLK: First World economy, Second World society, Third World culture.

THL & JEHL: Do you see the city as an inclusive or alienating place, or both? How might this sentiment be represented in the public and/or private spaces of your home city?

JLK: It is both obviously. Hong Lim Park in Singapore is the only place designated by the State for public protests. It is a place where concerned citizens can come together for a socio-political cause, but it is also a strictly regulated space. Every year, activists for LGBT equality organize their rally called Pink Dot there. This rally is an inclusive event, as it welcomes queer people of all stripes and our straight allies, but it is also a constant reminder to me that Singapore does not accord equality to people like us.

THL & JEHL: If the city could answer your questions, what would you ask it? Why are these important issues to you?

JLK: Will you ever change your survival and authoritarian mentality, which prioritizes economic development and political control above all else? How can you be changed? Will you remember me? And how will you remember me?

THL & JEHL: Also let’s consider the reverse. What would your city ask you? Why?

JLK: Who are you?

THL & JEHL: Is there a poetry community in your home city? If so, do you actively participate in its activities?

JLK: Singapore’s poetry community is small, so the feeling among us is that everyone knows everyone. I visit Singapore every summer when school is out. On every visit I organize readings under the banner of “Singapore Unbound,” a non-profit organization that I’ve founded to build cultural exchange and understanding between Singapore and the United States. In Singapore, I’ve organized a memorial reading for Justin Chin, the writer who was born in Malaysia, grew up in Singapore and moved to San Francisco, where he died. Last year, I organized a reading commemorating the writing of the second book of poems by Goh Poh Seng, who moved from Singapore to Canada and died there. Other readings feature authors I’ve invited to participate in the Singapore Literature Festival in NYC (Singapore Unbound’s flagship event). This year, I’m going to teach writing workshops for the first time. I hope that what I’ve learned in the United States will be useful to younger poets.

I think a collective identity is less important than poetic collaboration and mentorship. Writing is essentially a solitary activity, and it must be protected as so, in order to produce an authentic poetry. Still, younger writers can benefit from feedback on craft and advice on careers, while older writers can benefit from informed and critical attention from the younger generation.

In the United States, I give regular readings, most frequently after a new publication. I’ve read in New York, of course, and in D.C., Boston, San Francisco, New Orleans, Minneapolis and Decatur, in Georgia. In New York itself, I’ve read in a range of venues, from the well-established 92nd Street Y to a dive in downtown Manhattan. My arts organizing here centers on Singapore Unbound. The biennial Singapore Literature Festival in NYC brings Singaporean and American authors together for readings and conversations. The Second Saturdays Reading Series features writers from both countries in monthly gatherings. I also edit the blog Singapore Poetry, which runs a series of book reviews, written by Singaporeans of American books and vice versa. I’ve launched a small press called Gaudy Boy to bring works by authors of Asian heritage to an American audience. Through Singapore Unbound, I keep in close contact with the poetry community back home and contribute to the poetry community in New York. In terms of NY literary organizations, my strongest affiliation is with Kundiman, whose mission is to develop and promote Asian American literary voices.

THL & JEHL: What impact has your government’s support/lack of support for the arts had on the development of Singapore’s poetic community?

JLK: The Singapore government is pouring in a great deal of funding for the arts in the hope of making Singapore a “Renaissance City,” a vibrant cultural center which attracts global creative talents. The motive is primarily economic, and so the arts are seen in a perniciously instrumental fashion. This is an influential view, which must be fought against constantly by arts practitioners who hold that the arts are valuable for themselves. Some editors and writers have censored themselves in the hope of receiving state monies for their publications. A recent anthology of writings about Lee Kuan Yew was submitted to the Attorney-General’s Chamber for vetting before publication. Throughout its pages, the anthology referred to Lee Kuan Yew as the Man, instead of by his name, in fear of libel laws, which the government has invoked frequently to smash their opponents. Money is corrupting, and the dependence on state funding has led to a certain timidity in Singapore poetry. This is why I do not seek state funding for the activities of Singapore Unbound. I want it to be thoroughly independent of the state and to provide an example for self-reliance.

THL & JEHL: Overall, what impact has local poetry/literature/arts made on the cultural imaginary of Singapore? How has this altered or added to existing perspectives of the city?

JLK: An index to the influence of the arts may be seen in state suppression. Tan Pin Pin’s documentary film, To Singapore with Love, was restricted from public screening because it told the stories of political exiles. The National Arts Council withdrew a publishing grant from Sonny Liew’s graphic novel, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, because it depicts an alternative view of the tumultuous politics in the 1960s. These acts of suppression have limited the impact of these groundbreaking works. Most Singaporeans are still hard pressed to name more than one or two Singaporean writers, filmmakers and visual artists, beyond the genre authors seen in chain bookstores. They are much more familiar with the names of TV actors, who repeat for them familiar narratives about themselves and their country. Singapore poets are making a strong effort to spread the gospel, so to speak, by doing readings in schools and public spaces and by organizing events such as the annual Singapore Poetry Writing Month, which attracts hundreds of participants. I hope such efforts will grow the audience for poetry and throw up a strong poet or two.

Comments