It begins, like many things, with an egg. One hot and humid Taiwan summer day (is there any other kind?) my mother came back with a bunch of fried eggs she’d gotten from a street vendor, all in their individual unsealed plastic bags with a smash of sauce. “來吃早餐!” she called.

Each egg was nothing short of a miracle. To this day, more than a decade and a half later, I cannot accurately describe it. I can say it was sunny-side up, and that it was not runny. I can say it was seasoned with something that had soy sauce in it, but it didn’t really taste like soy sauce. I can say it was sweet, and somehow also buttery. There was some spice in it I couldn’t figure. It was what every fried egg aspired to be — the paragon of fried eggs.

I have no idea where this egg came from, and I will most likely never find it again.

This happened to me in Taiwan a lot — I would find something delicious, take it for granted, and then lose it. This happened for a couple of reasons: 1) I was a child, and 2) every time we were in Taiwan, we were whisked around by my relatives who simply brought us to each place (or brought food back) as if by fortune, like we were pre-destined to eat there. There was a place in Tainan by my grandmother’s house where we would get this amazing toast almost every day for breakfast, with either chocolate or rainbow sprinkles — yet another food item that I cannot describe in a way to do it justice. (Just in case you are wondering, it is not brick toast. It is not fairy toast. For years I have combed the internet for this toast).

Eggs are also the first thing I learned to cook. One day my mother was gone and I was in the house with my three younger siblings, and we were all hungry. A thought came into my head — problem … solution! Why don’t I cook? Something simple, because my mother always said the stove was dangerous.

I turned to my siblings like a game show host.

“Remember the egg we had in Taiwan? The one that was really good?”

“Yeah!” they chorused.

“I am going to cook that egg!”

I got out the pan and the oil. I had seen my mom and dad cook eggs before, and I was pretty sure I had it down. Oil, egg, let it crackle, maybe some soy sauce. But this one was going to be better. My first egg, and I was going to knock it out of the park. I busied myself with my invention, narrating my process to my siblings like one of the chefs on the cooking shows on PBS. “To get that sweet taste, I’m going to add some cinnamon,” I expounded. “Most people don’t do this, but I think it’ll really give us the taste we’re looking for.”

“Now,” I announced, flourishing the egg on a plate in front of my younger siblings, “taste the egg. Is there something missing? Something that could make it perfect?!”

My sister Joanne, being the true cheerleader that she is, replied, “No!”

I also took a bite of the egg. “Well, there is,” I conceded, with some embarrassment (I truly had not expected her to say that it was perfect). “It’s missing something.” A pause, as everyone took this in. The spirit of showmanship kicked me.

I brightened and declared, “Next time, I’ll find it!”

Spoiler: I have not yet found it.

***

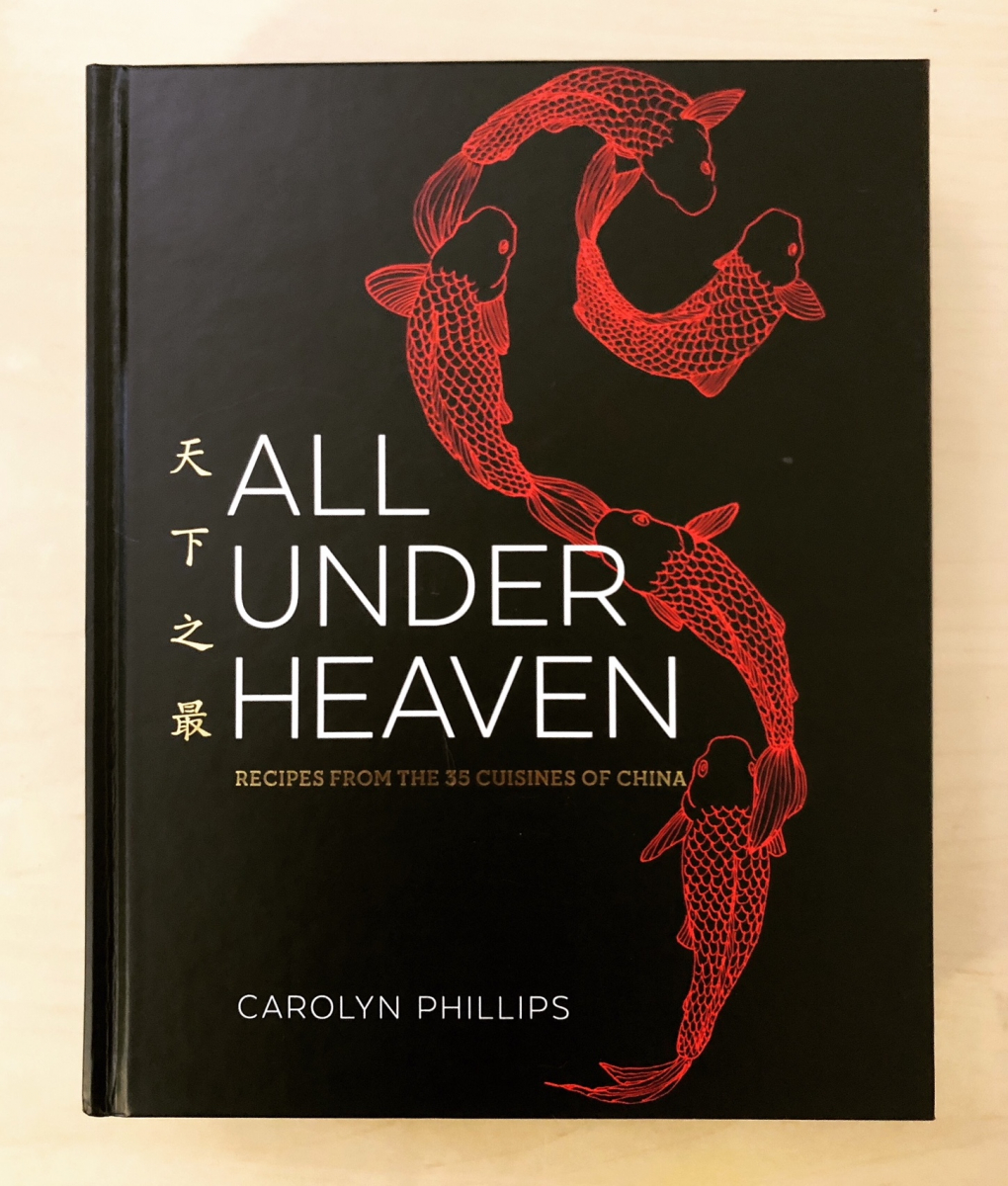

The only Chinese cookbook I own, I don’t even actually own — I had convinced my (white) roommate to buy it. It is Carolyn Phillips’ expansive All Under Heaven, and I’m extremely aware that Phillips is a white lady. I have recipes that I got from my mother, but, like the meme about Chinese recipes (“Chinese recipes, as handed down from mother to child: season it with a pinch of this and some of that. You want the exact amount? Feel it in your heart. Ask the stars. Yell into the void.”), none of them are formalized “recipes” and that’s not how I cook. Once my friend asked for my “simple” puttanesca recipe because he wanted to re-create it while he was away and received this from me:

Puttanesca

- 2 can anchovies

- large can chunky style crushed

- small can diced

Anchovies + garlic + olive oil + crushed red pepper flakes

Crushed tomato + diced + capers + olives

Parmesan reggiano on top

Add whatever fish you want

Oh remember to boil water for noodles first because that takes the longest

Watching my mother cook, it seemed like she cooked organically, out of some knowledge that grew out of her, like a tree making apples from water and the sun. My father also cooked — not always the same dishes, but seemingly in that same way. Sometimes she would find recipes in books or magazines she would try, but those would generally be for different cuisines, like Italian. When I asked my dad how he learned to cook, he said it was by watching. Sometimes I would ask my mom how to make certain things, and sometimes I would get fed up because it seemed like a meandering story, all description and no plot. As we got older and everyone got busier, slowly she stopped cooking the same way. We started eating more microwave dinners, more ready-made stuff she could heat up in the 電鍋.

With this in mind, I approach All Under Heaven like the way some white people approach a gilded tome of the complete Lord of the Rings — with wonder, mystery, curiosity, a slight sense of possible shared ancestry, combing the book for Elvish/Chinese words I know, recipes that look familiar.

All Under Heaven is this huge recipe book of 300 recipes from different areas of China, replete with history and background shaded in. Phillips said she wrote it because after living in Taiwan, she came back and couldn’t find the same depth of dishes in the United States (a pain I also share). She also says that over time, Taiwan itself has lost a lot of these recipes as the past great chefs die or move elsewhere and there is no longer the same apprenticeship/chef relationships (I do not have the knowledge to comment on this, except to say the street food in Taiwan is still unparalleled). It is 500+ pages, including chapters on fundamentals, basics, techniques, plus glossary and buying guide. It is very hefty (I’ve had smaller textbooks), is illustrated and has gold etchings on the side. It was published in 2016.

I first discovered it at a house party in Palms, Los Angeles. Browsing my friend’s bookshelf, I started thumbing through the book and felt smacked in the face when I found, on page 230, a recipe for ginger milk pudding.

Junior year of high school I had found a Chinese recipe online in a blog post on Xanga, of all places. This was back when Chinese recipes were few, most of my classmates thought Panda Express was Chinese food and asking my mom for recipes was never straightforward. The recipe was called “ginger crashed with milk” and came with a charming backstory about the writer finding out her Chinese mother-in-law had secretly kept some tips from her so that hers wouldn’t be as good. The next time I hung out with my high school boyfriend and my neighbor, I convinced them to make it.

“Are you sure this is a real recipe?” Larry, my neighbor-friend, was skeptical. I didn’t blame him. First, I often had some crazy ideas, like when I said we should cut down a tree in the neighborhood park, carve it into a canoe and sail down the river. Second, he was multiracial (if memory serves me right, his dad was Malaysian and his mom was white) and therefore did have somewhat of a grasp on Chinese cooking. Third, this recipe did sound insane. It was supposed to form a pudding but without any gelatin. The fresh ginger juice + the hot milk was somehow going to magically perform the congealing/knitting together. It also was, perhaps true to the spirit of the mother-in-law, sparse on specific instructions. We followed the recipe diligently as best we could, using a garlic press to force out the ginger juice, mixing it with sugar, heating up the milk and then pouring it into the bowls with the ginger juice. We ended up making not very good ginger-flavored milk.

“I don’t think this is a real recipe,” Larry concluded.

At some point, my boyfriend’s mother peeked into the kitchen. “Austin, can I talk to you?” she inquired. Later, I found out that she had very sternly asked him if we were high.

Now, years later at a house party, I was finally vindicated. “It is a real recipe!” I yelled out of the blue, freaking out my friend’s girlfriend. “I’m telling Larry!”

***

Every time I go back to Taiwan I have this immortal fear that this time everything will have changed so radically that it is completely unrecognizable as the Taiwan I remember. That Taiwan has finally outstripped me and run far, far away to a new place I cannot follow. Like the elves in LOTR, they have left for the Undying Lands without me. That finally, it has happened — I am no longer Taiwanese in any way, and all my memories are now a roadmap to a place that no longer exists. That I’ll finally be revealed for who I am: a deluded tourist.

I recently went back to Taiwan to visit my brother. In the weeks leading up to the trip, my partner, who has never been to Taiwan, was brimming with excitement. “We’re going to go to Taiwan!” he would call out every so often. “Aren’t you excited?”

I have a tic — when I’m nervous or anxious or bored or sometimes just because, I will pluck at the skin on my right elbow. Now I had plucked it so much the skin had developed an elephantlike shell over it. “Yes!” I would say. “Yes, I am.”

Here’s the obvious: food is coded. Fried eggs aren’t inherently coded to be “Chinese” or “Taiwanese,” and yet it is one of the foods my mind will automatically associate with Taiwan. In that egg I see my grandmother’s tall and skinny three-story house and the dirt roads on which I would endlessly bike. I see Taipei and my eternally grumpy uncle, the one that’s also secretly nice. I feel the oppressive humidity and remember fighting canopies of mosquito netting on four-poster beds, but also sleeping on the floor on mats with my cousins, giggling into the night until we all got in trouble. I remember how my mother was always happier when we were in Taiwan, how she actually smiled and laughed. That egg is one of my Proustian madeleines, and honestly, I wish I could have chosen a more “authentic” meal. At this point I even have to seriously ask myself: What do you even remember? Did it actually taste that good? Did it really have cinnamon in it? What if you’re just trying to make something that doesn’t exist, and nothing will ever be good enough?

In continually attempting to re-create it, while living as an Asian American and what it means, how it spans in front of me, while owning a book by and learning about my own cuisine from a white woman — there’s a lot of questions here that I still don’t know how to answer. When will I know? I ask myself. The confidence Phillips must have had to write this cookbook — when will I have that?

In the meantime, I keep trying to make that damned egg.

Epilogue

A few weeks ago I mysteriously and fortuitously received a free bag of stroopwafels. It would not be too much of an exaggeration to say that they basically showed up at my front door, begging to be eaten.

“This is strange,” I said, after ripping open the bag and eating my third stroopwafel while my partner made dinner. “I wonder why they are so good.”

“I bet they are German,” my partner answered.

“They’re Dutch.”

“Same thing.”

“No, the Dutch have told me very strongly that they are Germans, but with humor,” I sagely responded.

Later, a friend from the United Kingdom chimed in. “As a Dutchman, can confirm.” Then he also added: “Look up hagelslag. Dutch people put that on bread to eat like utter maniacs.”

Remember when I said there was an amazing toast in Tainan that I got for breakfast that I have never found since? Turns out it was hagelslag, and now I eat it at night, as dessert.

Comments