One year ago on January 27, 2021, Corky Lee, a beloved photographer, journalist and activist, passed away from complications of COVID-19. His passing was a loss felt deeply throughout the Asian American community, whom he had served, documented and celebrated through his vivid images. (Hyphen featured a spread on his work in Issue 3, published in 2004.)

Shortly after Lee's passing last year, we reached out to a few in the community who knew him and/or were touched by his work for some thoughts about Lee, his career and his impact and legacy.

(For a reflection on processing anti-Asian violence through the work of Corky Lee, read this piece written by one of our editors, Viviane Eng.)

Bob Hsiang, photographer

I've had Corky Lee on my mind for the last couple of weeks. I felt he was going to emerge victorious over his serious illness, pick up his Nikons and get back to work. Then sadly he lost his battle to Covid-19, leaving hundreds of his friends and associates in tears and mourning his sudden departure from the material world.

I've had Corky Lee on my mind for the last couple of weeks. I felt he was going to emerge victorious over his serious illness, pick up his Nikons and get back to work. Then sadly he lost his battle to Covid-19, leaving hundreds of his friends and associates in tears and mourning his sudden departure from the material world.

I met Corky after college when we were becoming involved in the nascent Asian American movement. He had already began his activism in Chinatown while the genocidal Vietnam War raged on. The flames of revolutionary fervor and societal change exploded on the streets of the United States: Women marched to throw off the shackles of male chauvinism and toxic masculinity (as it is termed today). The LGBTQ communities marched for liberation and fought against homophobia. People of color, of every stripe, were awakening to the centuries of oppression and discrimination by the U.S. government and a white majority that, despite the Civil Rights legislation of 1965, still ruled with vestiges of Jim Crow and implicit bias throughout the court system, hiring practices and the microaggressions of daily life.

I had begun my photojournalistic pursuits in college while covering the Black Power struggle and the anti-war rallies and demonstrations starting at the Pentagon in 1967. I returned to Chinatown to live in a political collective of like-minded Chinese Americans whose aim was to study revolutionary politics and organize the community. It was the first time I had learned about the World War II internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans. Corky had left Queens College and we then set up the Asian Media Collective with my future life partner, Nancy Hom, and others. The Collective's loosely based raison d'etre was to disseminate progressive activities in the Asian communities of the New York area. We believed that the corporate media was not telling the truth about Vietnam and ignored the real struggle at home where radical changes were about to take place as people's consciousness was changing. We created slideshows with 2 projectors and showed them at various venues including universities where early ethnic studies departments were established.

Corky was learning photography on the streets; he would begin a 50-year journey of documenting the multifaceted Asian communities, centering on employment equity, racial profiling, police violence, the Vincent Chin murder, the demonizing of Muslims post-9/11 and the recognition of Chinese American World War II veterans. He was photographing just recently, I was told, a story about the Guardian Angels. Through Facebook, I was able to get a glimpse of Corky's camera work, even on the subways, where he used his cellphone and humorously mused about passengers across from his seat. And I wonder now about the health risks one takes on public transit.

Now Corky is no longer here physically; however, his images will be forever, his spirit and love for the community imbued in the content of his thousands of photographs. Dropping his photojournalistic credo, he coined the phrase "photographic justice," implying that a singular constructed image can initiate the revisiting and condemning of the injustices that have historically plagued the textbooks and films from the past. The idea draws from guerilla theater and speculative photography. That is his lasting legacy and gift to future generations.

We didn't communicate much in the last 50 years, but I was always aware of your presence whether in Ogden, Utah, East Broadway or on Kearny Street in San Francisco. I will miss you, Corky. You done good, brother.

Erin Pangilinan, journalist and former Hyphen contributor

Haiku for Corky Lee

“He captured our lives.

Our Asian America.

Moments of struggle.”

I was proud to know and remember Corky Lee. I met Corky at an Asian American Journalist Association (AAJA) Convention years ago in 2011. In this photo, myself, An Rong, Joz Wang and others with Corky are sporting our Vincent Chin T-shirts in Detroit, Michigan. The place holds historical significance given Corky’s contribution to the moment in the ’80s with the hate crime, the violent killing of Vincent Chin. This was just one of many significant moments Corky contributed to in his career in photojournalism and activism.

As I pray for loved ones lost like Corky during COVID–19, I watch Warrior on HBO Max, which commemorates Chinatown in San Francisco and has a scene with the Golden Spike, referencing Chinese Americans’ contributions to the building of the Transcontinental Railroad. I learned even more about Corky’s response to that time.

Corky’s contributions included documenting us from our ethnic enclaves whether we come from our own version of Chinatown, Manilatown, Japantown and Little Saigon.

Corky reminds us about the place in history that Asian Americans hold at significant moments in time, including us back into the U.S narrative, one that often forgets or excludes even basic facts such as the 1875 Page Law and 1882 Chinese Exclusion Acts, our role in protests for civil rights from the ’60s and battling anti-Asian violence in the ’80s to the current moment of Filipino American nurses fighting COVID-19 on the frontlines. He documented moments of anti-Asian racism, but also captured the joy in many celebrations, taking photos at Asian American events from NY and all over the country throughout the decades.

We are at a loss of one of our best, most inspirational Asian American elders, community leaders, historians, artists and documentarians. He has a unique meaning to many of us in our own special way, more than he will ever know. He will be missed and remembered. His timeless work will continue to be relevant and educate our community on our struggle for generations.

Rest In Peace and Power, Corky Lee.

James Sobredo, Professor Emeritus at the Asian American Studies Program of Sacramento State University and photojournalist

In the mid-1990s, I noticed that many books on Asian Americans had photographs featured by “Corky Lee.” Although I spent my career as a professor of Ethnic Studies, I also maintained a life as a documentary photographer and even reached a point where my photodocumentary work on Filipino Americans was exhibited at museums and galleries.

In the mid-1990s, I noticed that many books on Asian Americans had photographs featured by “Corky Lee.” Although I spent my career as a professor of Ethnic Studies, I also maintained a life as a documentary photographer and even reached a point where my photodocumentary work on Filipino Americans was exhibited at museums and galleries.

As a photographer, I immediately noticed the huge number of photographs by Corky and often wondered who he was. I finally met him in person in 2015 at a national conference on Asian Americans in San Francisco. We got along immediately, and because we had much in common through documentary photography, it felt as if we were longtime friends. We met again in New York at the Filipino American National Historical Society national conference in 2016, had dinner together, hung out for hours and talked and exchanged notes about photography. Corky and I kept a regular correspondence via Facebook, mostly talking about Asian American issues and, of course, about photography. He was very helpful and generous in his comments and advice about photography and about working for and with our community.

When I heard the news about his coronavirus hospitalization, I immediately looked at his last Facebook message. Corky sent me a message the day before he went into the hospital. I almost cried. In retrospect, like many folks, I wished I had spent more time with him. I had this fantasy that we would spend time photographing the Chinese community in Spain, which is my second home. I am deeply grateful for his friendship and kindness, and I am so happy I got to know him. A signed photograph of Corky’s iconic image of the Sikh American draped in the American flag after 9/11 is displayed prominently in our home.

Pax vobis, Corky.

Take care, Dear Friend, and good luck on your next journey.

An Rong Xu, Photographer

In 2008, I was a freshman in art school, and I had just begun a project on Asian American families. As I was taking photographs, I had been seeking guidance and feedback from fellow Asian Americans. Bob Lee of the Asian American Arts center told me I had to meet Corky Lee. I went looking for Corky and serendipitously met him at a screening of Tad Nakamura’s documentary, A Song for Ourselves. When I introduced myself to Corky, he remarked that I looked familiar, and I felt the same way, but I couldn’t quite exactly put my finger on it.

I spent that summer learning from Corky, going to various Asian American events, from the Sikh Day Parade to a Japanese American Obon festival in New Jersey to a Filipino American day on Manila Ave in Jersey City and many other community events. But through this, I learned much about the history of the Asian American community.

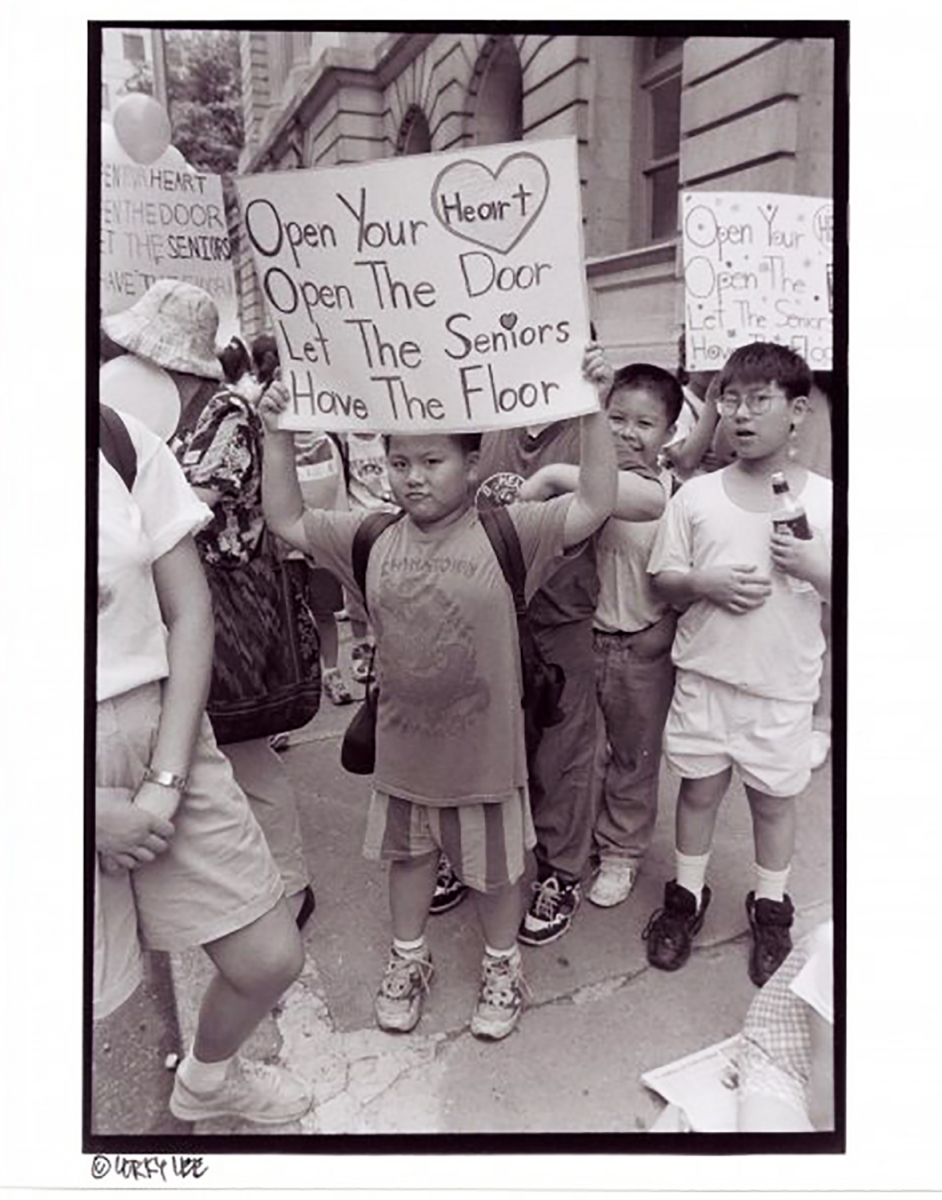

One day Corky showed up with an 8 x 10 print with a little chubby boy holding a sign protesting, and he asked me, Is this you? And it was: I was around 7 or 8 years old, holding up a sign and protesting for the city to open up a senior citizen center in the old police building. The moment I saw the photograph, I realized I still remember that day, someone taking a photo of me holding that sign. I couldn’t believe it, that many years later, I would go on to meet the photographer and be mentored by him.

I wouldn’t be who I am without Corky Lee, and I am thankful for all the time and knowledge he has imparted on me and the community.

Comments