On the morning of February 6, 2021, one could sense that something important was happening on the streets of Manhattan’s Chinatown. In addition to those grocery shopping and going about their regular business, others walked in small groups toward 10 pre-mapped destinations, as if on a pilgrimage of sorts, donning facemasks and morning beverages in hand. There was a trace of urgency in their strides and a somber yet empowered energy in the air—a reluctant type of tranquility that settles in after bearing witness to something that cannot be unseen, and deciding in that moment to, nonetheless, continue onward.

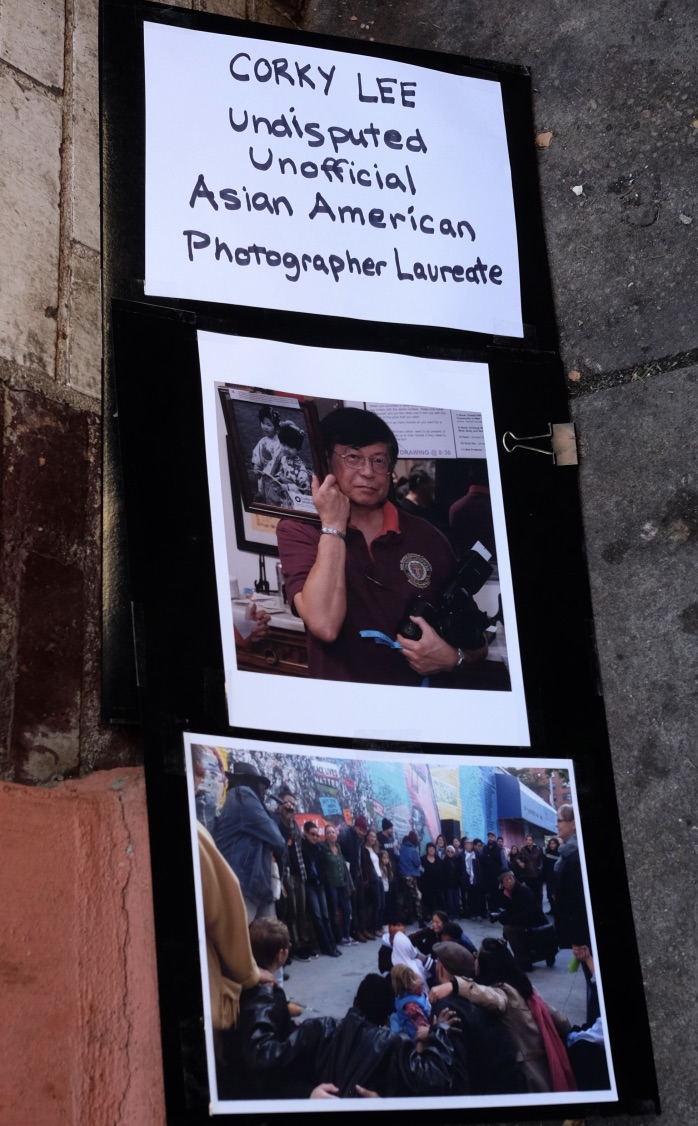

The people that lined the Chinatown sidewalks that morning were paying tribute to Queens-born photojournalist Corky Lee, who died from complications of COVID-19 on January 27 at the age of 73. Those close to him had picked out 10 of Lee’s most cherished Chinatown sites for loved ones to line up outside of, as his funeral procession took a last farewell loop through the neighborhood that the photographer so shaped and documented for the better part of two generations. As we come up on the one-year anniversary of Lee’s death, his body of work lives on and is just as important as ever.

Lee, who cheekily assumed the title of “undisputed unofficial Asian American photographer laureate,” was a fixture in the Asian American community, documenting moments both momentous and quotidian in Asian American life. He made headlines for helping descendants of Chinese migrant laborers reclaim their role in the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. He photographed Sikh Americans draped in American flags during a spike in anti-Sikh violence following the 9/11 attacks. But in spite of the plethora of communities Lee and his work touched, his loss is most intimately felt in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where up until his death and prior to the pandemic, Lee could be spotted on any given day photographing and organizing community events, commemorating seldom discussed moments in Asian American history, and passing on his vast knowledge of the subject to all who would listen.

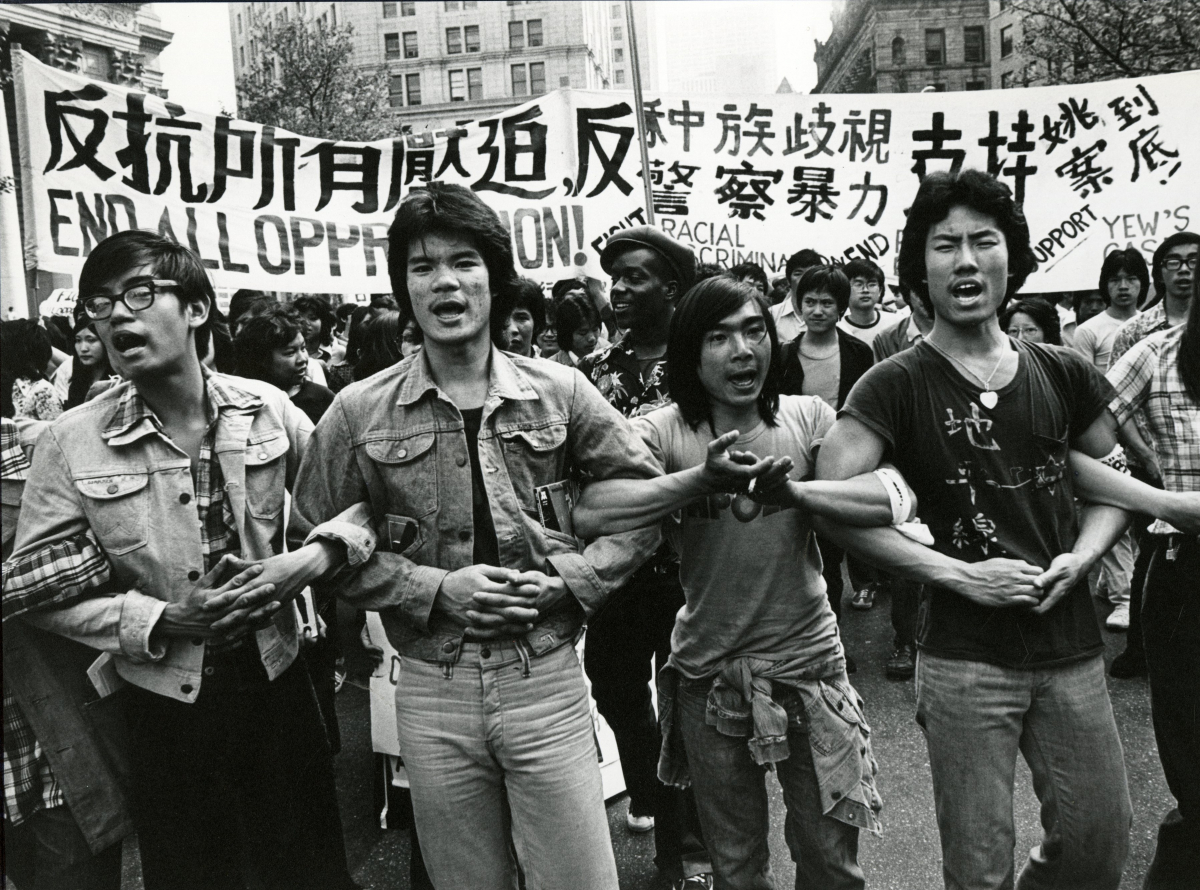

Though Lee certainly used his camera to capture quiet portraits of everyday life, he had a special affinity for documenting movements of resistance that flourished in the Chinatown community. Some of these neighborhood actions became catalysts for larger pan-Asian movements and interethnic coalitions, especially in partnership with New York’s Black and Puerto Rican freedom fighters.

“Corky didn't start off as a pillar of Chinatown, he and his friends started as pioneers,” said Christopher Marte, Councilmember for New York City's District 1. “They brought movement politics and community organizing into Chinatown, tackling societal issues through an Asian American lens in a way that nobody else was at that time. Over the decades, through his work as an artist and an activist, he got to be both a witness and a participant in a new story emerging in Chinatown.”

*

Amidst countless instances of racist violence these last two years that predominantly targeted Asian elders, including the murders of six Asian American women in Atlanta, the response from the Asian American community has understandably been a combination of fear, outrage, and shock. For much of this year, Asian elders were afraid to walk alone in their communities and their younger family members were equally at a loss with regards to how to protect them. Asian Americans across all demographics called for a greater awareness of the United States’ rarely-taught history of anti-Asian rhetoric, a history that many Americans—even Asian Americans—are ignorant of.

When it comes to our nation’s conversations about race, Asian Americans largely occupy an awkward invisible middle ground, one that predominantly reinforces a binary between Black and white. As put forth so deftly by Cathy Park Hong throughout her 2020 book of essays Minor Feelings, “Asian Americans inhabit a purgatorial status: neither white enough nor black enough, unmentioned in most conversations about racial identity. In the popular imagination, Asian Americans are all high-achieving professionals. But in reality, this is the most economically divided group in the country, a tenuous alliance of people with roots from South Asia to East Asia to the Pacific Islands, from tech millionaires to service industry laborers. How do we speak honestly about the Asian American condition—if such a thing exists?”

Throughout the last two pandemic years, protests surrounding systemic racial injustice against Black Americans captivated the attention of the world, forcing the country to reckon with its history of anti-Black racism. Though some Asian Americans showed up to support their Black friends and colleagues, many also wondered about where Asian Americans factored into the fight for racial equality.

Of course Asian Americans have not experienced the same sustained, systemic barriers to economic and social mobility and literal, physical safety that Black Americans have, and obviously have a very different history of repression. Yet, there are issues specific to Asian American communities that are often overlooked and scarcely discussed. For instance, it is not widely known that Asians have the highest poverty rate of any racial or ethnic group in New York City. Additionally, Asian American community organizations receive an astonishingly meager percentage of the city’s social service contracts and funding from the Department of Social Services. While some Asian Americans are wealthy, assimilated, and upwardly mobile, not all are. How, then, should Asian Americans figure into conversations about race? Especially in a moment when our own community is directly affected and it is up to us to lead the conversation? How do we fight our invisibility in this nation and how do we reconcile that lack of visibility with our desire to ally ourselves with other groups of color?

We can begin with Lee’s photos, so many of which are set in Chinatowns—ethnic enclaves born of white supremacy, anti-Asian violence, and de jure Asian exclusion laws.

“At a time of rising anti-Asian hate crimes, it is more important than ever that Corky Lee's work to document prejudice and discrimination be discussed not as a historical relic, but as a living conversation about how Asian Americans are perceived in America,” said New York State Assembly Member Yuh-Line Niou.

*

While there has been meaningful work done in terms of advocacy and education by Asian American activists and thought-leaders, there are still many Asian Americans who are unfamiliar with this country’s history of anti-Asian discrimination, suppression, and violence. Some of these might be first generation Asian immigrants who are not as familiar with American history, others might be younger, apolitical, upwardly mobile second generation Asian Americans. People in these populations, as well-intentioned as they might be, have outlooks on racial politics that are marked by internalized white supremacy.

Older Asian immigrants that have lived in the United States for a long time are likely to have had very direct experiences with racism, in that they might have been forced to live and work in ethnic enclaves, facing employment and pay discrimination elsewhere. For those who don’t have a firm grasp on the English language and especially for those that are undocumented, a natural tendency is to withdraw from civic life and focus on their own survival, a disillusionment born out of the state’s apathy—and perpetuation—of racially charged inequality. If this country sees me as lesser-than, what is the point of speaking out? Especially for other minorities to whom we owe nothing?

Similarly, college-educated Asian American Millennials, some of whom have inherited their parents’ disillusionment with political engagement, can also fall prey to internalizing ideas of white supremacy. They might not be explicitly fearful about expressing their political opinions, but rather view their own successes as being the product of “hustle culture”—working hard, not complaining, and ascending the socioeconomic ladder, and thereby perpetuating the model minority myth. Asian Americans that do enter the privileged class might find themselves wondering what the big fuss some minorities are making about racial inequality in this country: If I was able to work my way out of my family’s immigrant hardships, why can’t other minorities do the same when faced with theirs?

What these politically withdrawn elders and Millennials have in common is that they both likely did not have many opportunities to see people that look like them, brazenly advocating for their own needs—and winning.

“I still talk to a lot of my former students, many of whom are from Chinatown, but have since left the community,” said Karen Low, a longtime friend of Lee, fellow community activist, and educator. “A lot of them now are just really into themselves. How can we bring them back to the community? I think Corky’s photos play a good part in this.”

Lee’s photos, whose subjects—Asians with megaphones and raised fists—refute the notion of the meek “model minority.” Through them, we can clearly see that social justice progress doesn’t only happen by way of hard work and ensuing economic mobility. Rather, it’s activism within Asian communities like Chinatown, and across ethnic lines, that have allowed Asian Americans to have a say over their urban spaces and policies that affect them.

*

In the wake of the surge in anti-Asian hate crimes, some Asian Americans demanded swift police action or openly admonished other minority groups, without acknowledging that calls for increased police presence, surveillance, and a blind reliance on the criminal justice system would only put the lives of our Black and brown neighbors at risk.

For some Asian Amerians, the struggle by the Black community for equality and justice may, at best, seem irrelevant to their own concerns, and at worst, fueled by complex histories such as the L.A. Riots, when more than 2,200 Korean businesses were destroyed by demonstrations following the Rodney King verdict. For the Koreans whose shops were looted and burned to the ground, it was easy to see Black Americans as the culprits of the destruction, rather than the vast racial inequities, police brutality, and ensuing acquittal of King’s killers. It can be much simpler to think in the framework of division, rather than cohesion.

But Lee’s photos document the power and significance of coalition-building between minority groups.

For example, in 1974, Manhattan’s Chinatown erupted in protest because the DeMatteis Corp., a private firm responsible for building a housing co-op in the neighborhood’s Confucius Plaza, was refusing to hire Asian construction workers. Inspired by the African American Civil Rights movement, activists led by what would become the organization Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE), took over the construction site and forced a work stoppage. A few weeks after the protests, the DeMatteis Corp. agreed to hire 27 minority workers, Asians among them. Today, many Asian immigrant elders live in the 764-unit apartment building, the first major public-funded housing project built almost exclusively for Chinese Americans.

“When we took over the construction site of Confucius Plaza, construction workers from the African American and Latino communities came out to support us,” said Low. “Corky’s photos captured that, and it’s something that a lot of people don’t know. People now who are living in Confucius Plaza need to know that it was built by a lot of blood, sweat, and tears by our own people, as well as people from the African American and Latino communities. Many things that we now enjoy are the fruits of the Civil Rights movement. And who was at the forefront? Black people. We can’t negate those facts, but a lot of elders don’t know American history.”

Without education, many Asian Americans will remain ignorant about their own histories and the long history of coalition and allyship with other marginalized groups. No mainstream media or high school history class ever taught me about the Confucius Plaza work stoppage, or the enormous protests against police brutality one year later, when Peter Yew, a young Chinese American was arrested and pummeled by cops after he asked that police stop beating a 15 year-old whom they had stopped for a traffic violation. I was not aware that in both of these scenarios, Asian American New Yorkers marched beside Black Power activists and Latinx neighbors—that these minority groups drew inspiration from one another’s work and understood deeply that their histories and victories had always been communal. Fifteen thousand protesters showed up to fight for Peter Yew in 1975, efforts that resulted in the charges against him being dropped. It wasn’t until I was long out of high school that I learned about these protests, which ushered so many Asian Americans into the Civil Rights Movement. It was through Corky Lee and his acts of bearing witness that taught me how Asian Americans have confronted white supremacy in the past, and how we must do so again.

“Corky Lee’s work should totally be taught in schools,” said Yin Kong, Director/Co-Founder of Th!nk Chinatown.

From his early film portrait of a wholesale laundry worker encouraging people to vote, to pandemic era photos of Chinatown he’d uploaded to Facebook shortly before his death, Lee’s vast archive belongs consolidated somewhere. Whether it’s in a bound book or a gallery, Lee’s rich documentation should be accessible to students of all ages and backgrounds, because it’s through education, stories, and community that allows us to keep our people safe, join forces with other organizers of color, and unite in the fight against white supremacy.

“People interested in Asian American history should understand his work and what he did, especially because he was a self-taught photographer who took a very casual approach to documentation,” says Kong. “It was all about stories—standing there next to him and hearing them. One-on-one transference was what he was going for, which is the amazing part of his work. But now that he’s gone, I wonder what we’re going to do. I’ll be thinking about that for a while.”

Related Content: Those who remember Corky Lee pay tribute to him.

Comments