Above: Dinh V. Nguyen, the 61-year-old owner of the Ocean View shrimp boat in Biloxi, MS, said there has been no work since the BP oil spill. It costs roughly $5,000 to $7,000 to outfit a vessel before leaving dock, Nguyen said, and if the US Coast Guard deems the shrimp to be tainted before they reach port, the owner is forced to dump the entire cargo, resulting in a total loss for the journey.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the sparse coverage of the Asian American community in the Gulf Coast drudged up a familiar feeling in me — one of sadness, frustration and neglect. It’s a feeling that I have been working to overcome for most of my professional career, in which I have observed the media’s neglect of civil rights rallies of the 1960s and of New York City’s Chinatown after 9/11. To be thought of as a non-factor in mainstream media continues to leave lasting mental scars in the Asian American community.

As time passed, I often wondered how the Gulf Coast has changed. Were there visible signs of revitalization and rebirth? Thanks in part to filmmaker S. Leo Chiang, I gained a better understanding of the post-Katrina Vietnamese American community in the spring of 2010 after viewing his powerful film A Village Called Versailles. It was only a month later that the deepwater Horizon explosion and oil spill set off yet another incomprehensible crisis in the area, deeply damaging the shrimp industry heavily fueled by Vietnamese manpower and vessels. I saw only white fishermen interviewed in the news. Neglected, yet again — that same old feeling.

In early June 2010, as thousands of barrels of oil continued to gush, Piyachat Terrell of the Environmental Protection Agency’s AAPI Initiative contacted me, wondering if I had some time to visit the Gulf Coast and photograph the community. It was an opportunity to fill the media void.

During my six-day stay, mainly in New Orleans, LA, and Biloxi, MS, I spent my time with small businesses and unemployed community members. I dined in their restaurants and purchased items from their stores.

I discovered the youth who have contributed immensely to the salvation of the area through their energy and perseverance. Organizations such as Vietnamese American Young Leaders Association of New Orleans (VAYLA-NO) and Asian Americans for Change in Mississippi have helped to navigate their community through the bureaucracy and neglect. While embracing American values, the youth are pioneering their own path and carrying on the spirit of past refugees and immigrants.

As for the elders, who have weathered the transition to the South from Vietnam and Southeast Asia over the past 35 years, they are resilient, taking things one day at a time and slowly regaining a sense of normalcy. They have saved their resources for times like this. They look pragmatically at life through their faith, be it Buddhism or Christianity.

I hope my photographs provide some visual evidence of the community that will remind us all to pay more attention to the Gulf Coast and the Vietnamese population there. This is just my small contribution to fill in some of the gaps.

The Reverend Vien T. Nguyen feeding and raising a flock of chickens at his mother’s

home, something he also did while growing up in his native Vietnam. Nguyen is a local hero for galvanizing efforts to rebuild the post-Katrina Vietnamese American community of over 10,000 people. When he was honored for his work by President Obama during Asian Pacific American Heritage Month in May 2010, the president introduced him by saying, “Nobody messes with Father Vien. He tends to get what he wants.”

Hai Minh Tran, a 56-year-old unemployed arc welder sits on the open trunk of his car with his welding certificate and gear, ready to work at a moment’s notice. He even carries an electric rice cooker in his trunk. Tran had just left his local Workforce Investment Network Job Center in Biloxi, MS, after being interviewed for possible job placements. He has also been assisted by Asian Americans for Change, a nonprofit helping residents find work and social services.

An assortment of homegrown garden vegetables at the weekly Saturday morning community market. The market has run unofficially between 4 a.m. and 9 a.m. for the last 30 years in a small strip mall on Alcee Fortier Boulevard.

Local school children of all ages showing support for the continuation of after-school programs in New Orleans East.

The landscaped garden in front of the proposed Viet Village Cooperative Urban Farm, a plan to turn 28 acres in New Orleans East into usable community space. The plans include a sports field, community farm plots, a bio-filtration canal, commercial plots and a livestock farm area. Despite numerous efforts, the area has been deemed marshland and sits undeveloped.

A figure of the late Chinese American Sheriff Harry Lee of Jefferson Parish, a mostly White suburban area adjacent to New Orleans. “He was a sort of patron saint to numerous Asian-owned businesses throughout his district,” said photographer Corky Lee. “I saw his likeness in every Vietnamese and Chinese business I visited. There is even an oil painting portrait of him hanging in the Panda King Restaurant, the largest Chinese eatery in New Orleans. However, his views and treatment of African Americans made him a polarizing figure in race relations.”

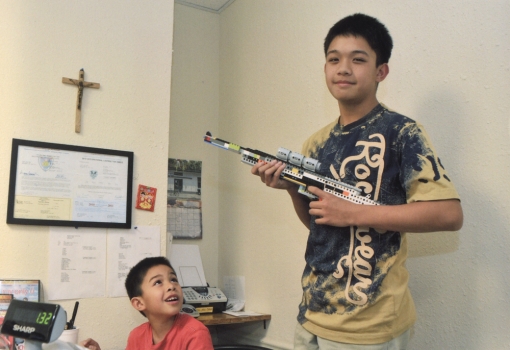

Nathan Balbon, 7 years old, and his 12-year-old brother, Neil, in their parents’ Pinoy Food Mart, the only store of its kind in the New Orleans area, located in a recently developed strip mall in Gretna. “The family had moved from California just seven months before I visited,” Lee said. “Neil is a big Lego fan and was proud to show me his Lego ‘rifle’ that shoots rubber bands.”

Persimmons, potted plants, inexpensive dry goods and even live and roasted rabbits ($35 each) are available to shoppers. Varieties of fish are sold in bunches of two, three

and four.

Corky Lee is working on a self-published photo book, tentatively titled Asian Pacifically America.

Comments