“Once upon a time, there was a little red hen who lived in a barnyard with her three chicks.”

I sat sprawled on the living room floor, reading aloud as my father lay on the couch, staring at the ceiling. As a 5-year-old girl, I insisted on reading to my dad, because I knew he couldn’t read to me.

When I was in kindergarten in Spokane, WA, I thought that my dad and I could learn the ABCs together. “ ‘A’ sounds like ‘ahhh’ and stands for ‘apple,’ ” I exclaimed with enthusiasm. My dad nervously laughed and left the room, embarrassed and ashamed. My father’s light skin, bright brown eyes and dense hair had marked his fate, preventing him from receiving a basic education. He is Amerasian — the child of a GI soldier and Vietnamese mother.

In 1986, my father immigrated to the United States with his biological mother under the Amerasian Homecoming Act, which allowed for children in Vietnam born of American fathers prior to 1982 to be brought to America. This also included Amerasians in Japan, Thailand, South Korea and the Philippines.

During war, relationships between foreign women and soldiers transpired under consensual and non-consensual conditions. What I know about my grandmother’s relationship with the GI soldier is limited. I do know that when my grandmother went to the military base to show the soldier their baby, he pulled out his gun, pointing at the baby, and told her to get “the thing” away from him before he shot it.

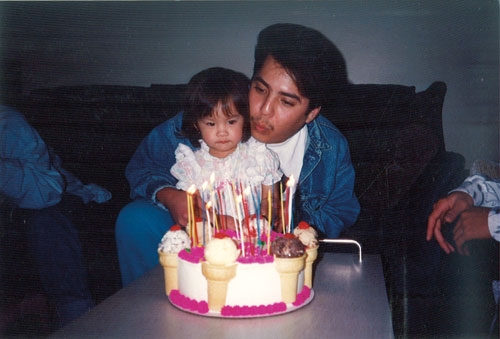

The author with her father on her second birthday.

Many Amerasian babies were abandoned or thrown into ditches due to the social repercussions of having sexual relations with a foreigner. A Vietnamese surrogate mother adopted my father for a time because his biological mother could not financially support him. His surrogate mother, my godmother, loved him and treated him like her own.

Yet she could not inhibit the bullying and cruel names: “half-breed dogs;” “the dust of life;” “My lai muoi hai lo dit (mixed child with 12 assholes).”

These were epithets regularly directed at my father, with his white features, for being half of the “foreigner” and “enemy.” Kids would tell him to go back to his dad’s country. Adults shunned him. His mother was ostracized for having a love affair with a GI. His peers put him into a bucket used for collecting rain and beat on the bucket with the intent of making him deaf. In the minds of the Vietnamese, Amerasians represented colonialism, the enemy and the infiltration of “the white man.”

The day that my father was to leave Vietnam, he hid. He did not want to leave his surrogate mother. His biological mother had reappeared in his life and made all the arrangements to resettle in the United States. A Catholic church in Spokane was sponsoring their trip.

My father was angry that his biological mother had abandoned him for all of that time, but his surrogate mother knew this was for the best. To convince my dad to get on the plane, she told him that she never loved him and that he was an inconvenience to her family. These hurtful words were enough to get my father on the plane, his heart broken.

Some Amerasians found their fathers in America and reconnected with them; many did not. Many American soldiers involved in these love affairs already had families back home. It was also difficult to keep any photos, love letters and paperwork for reference: under the Viet Cong regime, personal belongings could be searched and seized at any time, so these items were burned to prevent punishment for being involved with the enemy.

Granting my father and all Amerasians automatic citizenship — just like the children of any other American father — would be the first step toward addressing the wrongs they have faced: as outcasts in their homeland, as children often denied the love and support of one or both parents, as part of an invisible history. With the United States and Vietnam at war, a sense of home was missing for them.

Amerasians should be able to reformulate their identities here. With automatic citizenship, they might finally feel like they belong somewhere and that someone has finally taken responsibility for them.

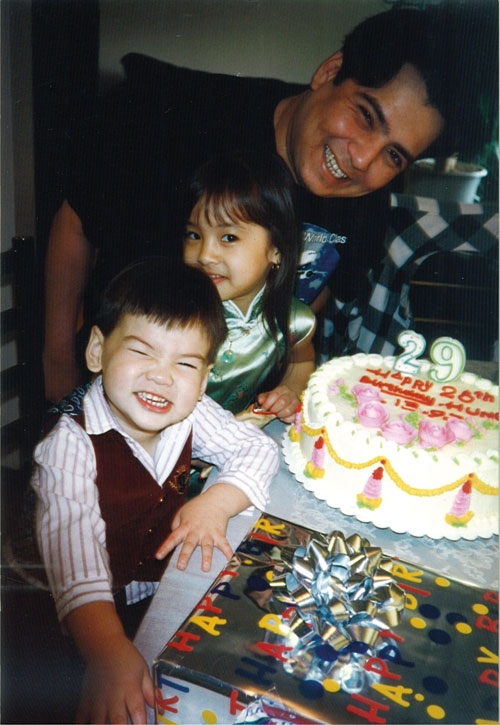

The author, age 6, with her father and younger brother, Tai.

The movement for citizenship among Amerasians has been a recent one, with leaders all over the nation trying to build a coalition and develop nonprofit organizations. I have worked to reintroduce in the House of Representatives the Amerasian Paternity Recognition Act, which would give the children who immigrated here under the Amerasian Homecoming Act automatic citizenship.

The act acknowledges that these children are truly Americans and that we are responsible for them since their motherlands have abandoned them. Chances are low that it will pass the Judiciary Committee. A stigma persists surrounding immigration and the idea that automatic citizenship could lead to an influx of immigrants.

Regardless of the status of the legislation, this work helps recognize the existence of Amerasians in United States history. I benefited from policies that allowed my dad to raise me here. I owe this to my community, knowing that the first generation of Amerasians could pass without notice.

The day I reintroduced the bill in the House of Representatives earlier this year, my dad called me and said that he doesn’t care if this legislation ever passes or not. I’ve already proven how much I love him.

Thuy-Anh Vo is a senior at Gonzaga University who intends to pursue immigration law.

Comments