Writer Nina Kahori Fallenbaum

Photographer Lisa Cates

Some say that Asian America began in Louisiana. In the late 1700s,

Filipino sailors escaped Spanish galleons and started shrimping the

hot, humid Gulf Coast, where the weather reminded them of Southeast

Asia and the water teemed with oysters, lobsters, scallops,

crab, crayfish and shrimp. After the Vietnam War, new waves of

Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrants settled in the area, indelibly

shifting the region’s mix of food, culture and history.

But neither history nor affinity could protect New Orleans-area

Asian Americans from the multiple disasters of the last six years.

Neighborhoods were just beginning to recover from 2005’s Hurricane

Katrina when the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded in April

2010. Fishermen watched the news nervously, hoping the spill

would be contained quickly. It wasn’t. The oil — between 55,000

and 62,000 barrels a day — flowed for 87 days into the gulf before

it was capped.

For the Vietnamese Americans in the area whose labor — fishing,

cleaning, sorting, packing, cooking and selling — makes up

about one-third of the gulf’s seafood industry, any hard-won stability

after Katrina suddenly vanished. But this disaster presented no

riveting Superdome, no wrenching images, to engender sympathy

and assistance — only an ongoing series of setbacks and recalculations

for this community that has been so central to the ocean

economy for decades.

They now face protracted compensation battles, diminished

business and skepticism about the future. Yet as local Vietnamese

Americans apply some entrepreneurial thinking and a rolling up of

sleeves to work the land instead of the sea, a new chapter of Asian

America seems set to begin in the region.

---

“The bread will rise again — it just kneads time.”

— sign on Vietnamese-owned Le Bakery and Cafe in East Biloxi, MS

Shortly after the spill, the Rev. Vien Nguyen of the largely Vietnamese

New Orleans parish Mary Queen of Vietnam travelled to Cordova,

AK, to understand how long it would take for New Orleans

to recover. What he saw there, at the site of the 1989 Exxon Valdez

oil spill, alarmed him. Cordova’s local fish, such as herring, continued

to appear for the first three years after that spill, but then

disappeared. Scientists say herring need four years to grow from

spawn to eating size; the spill occurred right at spawning time.

When Nguyen visited over two decades later, the fish still hadn’t

returned to Cordova. “Will it ever return to normal?” he asked. “We

don’t know.”

When the BP oil spill started gushing into fishing waters, it hammered

an industry that had been struggling for years. Until the early

2000s, the gulf provided most of the shellfish eaten in the United

States. In the last decade, however, the growth of commercial fish

and seafood farming in Southeast Asia (and the subsequent influx

of low-cost seafood) has bitten deep into the American seafood

industry. Vietnamese Americans had been picking up the slack in a

backbreaking industry few Americans wanted to do, but these economics

have made it even harder for them to make a living.

Phuong Nguyen has worked in and out of the crab industry for

30 years. He learned how to fish in Vietnam before immigrating in

1982, eventually buying his own boat and house after many years of hardscrabble work.

“They say fishing is for people without degrees,” he said. “When

you have a degree, you find some other job.” He said, laughing:

“There is no college or anything down here. We’re 20 miles to the

end of the world.”

Before the spill, Phuong Nguyen worked full time as a commercial

crabber for seafood restaurants and wholesalers in the New Orleans

area. Now he passes time by tending his backyard chickens,

trimming his rosebushes and watching the ocean and his finances

in equal measure.

Most of his neighbors work two or three jobs, trying to diversify

their incomes while they wait to learn whether the gulf is safe.

He raises chickens for eggs and meat and grows herbs, zucchini,

cauliflower and other vegetables in his backyard. While he received

some relief money from BP, he’s not sure if fishing in the area will

ever become a viable occupation again.

As a fisherman who still eats his own catch (the waters are sporadically

opened for fishing), Phuong Nguyen feels confident about

the safety of gulf seafood post-spill, primarily because local health

department officials check contaminant levels almost daily before

determining whether fisherman can sail out.

While some customers may have hesitated after the spill to buy

frozen seafood labeled “Gulf Coast,” consider this: 84 percent of

seafood eaten in the United States is imported and almost none of

it is checked for impurities or the presence of antibiotics, which are

routinely used in high-density fish farms to quell infections. This gaping

hole in our food safety regimen has increased interest in wildcaught,

domestic seafood — the kind that Phuong Nguyen catches.

---

Recipe: Coming Home Chicken Soup (Chao)

"Chao is just rice cooked

with a lot of water. I call it swill. You can do many different flavors,

but the most common is chicken.

Boil a chicken with onion, and take

out the chicken. Separate the meat from the bone, and drop the carcass

back into the juice. Keep on simmering, boiling it, and just when you’re

almost ready to eat, drop a handful of rice into the pot. Not too much.

After about half an hour, it should be ready. In the meantime, break

the chicken down into smaller pieces. Before you serve, you can put all

the chicken meat back in or keep it separate and let people put their

own in as they eat. Normally you would add green onions, chopped

cilantro and a little bit of black pepper. If it’s not salty enough, add

a little fish sauce. That’s it. It’s good for sharing." — The Rev. Vien Nguyen, who often serves this to guests and family members returning from long trips.

---

To get to Phuong Nguyen’s house in Buras, you take

Louisiana Highway 23 about an hour and a half from

New Orleans, along the final threads of the mighty

Mississippi River before it empties into the Gulf of

Mexico. On your left are hulking white cylinders and

the triple-fenced security perimeters of the refineries.

This is the oil economy, processing the oil that we

pump in our cars, that becomes plastic, that fuels our

air conditioners. According to the Department of Energy,

approximately 37 percent of the energy Americans

use comes from petroleum. Its main use is for transportation:

cars, trucks and planes to carry us and the products we consume.

The agency reported in January that American oil refining was at its

highest levels since 1982, with almost half of that refining going on

in the Gulf Coast.

On your right is where the locals live. From rambling houses dotted

with chickens and old cars, local anger and pride spill equally

from hand-scrawled signs tacked to the fences: “Damn BP!” and

“God Bless America.” Gas stations stock fishing lines and nightcrawlers

in plastic foam boxes next to the Cokes. This is the fish

economy.

To the tourists enjoying New Orleans’ restaurants or Biloxi’s casinos,

the fish and oil economies are largely hidden from view. Even

more hidden are Vietnamese American families and their contributions.

“The government and BP claim they have scooped up 75 percent

of the oil,” the Rev. Nguyen said, a note of anger rising in his

voice for the first time. “But will we be like Alaska, where the first

three to four years we don’t see it? But then when we see it, it’s too

late?” he asked. Mother Jones reported that oceanographers found

the chemical dispersant used to break up the oil as far as 200 miles

from the well head, and three months after the accident, much of

the oil still had not broken down. Government agencies responsible

for both environmental and human health agree that the use of this

chemical is experimental, with unknown effects.

The twisted relationship between the oil and fish economies is

nowhere more evident than in the protracted compensation battles

that began almost immediately after the spill.

For families whose income came in both dollars and fish, it’s difficult

to quantify the losses from the spill. Local fishermen like Phuong Nguyen have long eaten, traded and shared their commercial

catch. People fished for their own families, brought crabs to church

picnics and traded for things they didn’t catch.

When BP and the US government began devising a system

to compensate losses, these non-commercial “subsistence uses”

were either left out or worse, accused of being fraudulent. A group

of pro bono lawyers and community activists are now advocating

for Asian American fishing families who’ve suffered significant

loss of subsistence use. They hope to convince Kenneth Feinberg,

claims administrator for BP’s compensation fund, that not all losses

can be shown in ledger books.

There are laws designed to protect victims of large-scale environmental

disasters (the Oil Pollution Act and Clean Water Act

among them), but their parameters are hard enough for native English

speakers to understand, let alone those that struggle with written

English or are not literate in any language.

Jennifer Vu is a New Orleans native and former staffer of US

Rep. Joseph Cao, the first Vietnamese American elected to Congress.

Her office joined local groups to hold multilingual information

sessions after the spill and criticized BP for failing to provide information

for limited-English speakers.

“Feinberg still hasn’t held an interpreted town hall,” she said, six

months after the spill. While over 16,000 subsistence use claims

have been submitted to the Gulf Coast Claims Facility, just two Vietnamese

families have been paid so far, at less than $5,000 each.

According to Vu and others assisting the claims process, what’s

most needed now is nationwide awareness and legal assistance

as residents and community groups prepare for what may be long,

drawn-out court battles.

---

Recipe: South Vietnamese Bitter Melon

"This is the kind of dish we have only at home, never in restaurants: Mix shrimp paste, sugar, red pepper and lots of lime juice into a sauce. Shave raw bitter melon very thinly. Dip in sauce and eat over rice." — Jennifer Vu, New Orleans native

---

The uncertainty in the seafood industry goes beyond those who

work the ocean. Many Asian Americans have capitalized on New

Orleans’ food-loving culture, infusing their own flavor into a plethora

of boiled-crab takeout joints, seafood po’boy shops and other

small restaurants (one popular New Orleans Japanese restaurant

serves edamame with chili sauce).

Beau Nguyen and his wife, Laura, operate Singleton’s Mini-Mart, a convenience store with a small lunch counter, in the Uptown

neighborhood of New Orleans. Their shrimp po’boy is a hulking

mass of fried seafood on a French bread roll, best washed down

with a cold beer or iced tea.

Beau Nguyen of Singleton's Mini-Mart with his backyard herbs.

Beau Nguyen of Singleton's Mini-Mart with his backyard herbs.

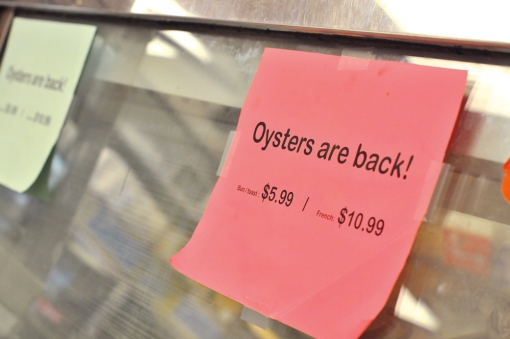

Since the oil spill, the couple has seen fewer customers and

higher seafood prices; oysters were off the menu for almost a year

after the sensitive bivalves and their nesting beds reacted to the

spill. The couple struggled to convince customers that their food

was safe. To recoup their losses, they added a new Vietnamese

weekend menu: grilled pork with rice noodles and pho advertised

as a “Hangover Remedy” for nearby Loyola and Tulane students.

The new menu is popular, but it’s much more work to produce two

entirely different menus.

Beau and Laura’s success can be attributed not just to their

food but also to the relationships they have built in their multiracial

neighborhood. Beau stayed in the shop through the terrors of

Katrina, and customers still talk about the food he gave to neighbors

and the big pig he barbecued in his parking lot after that hurricane.

Although Uptown is considered a wealthier neighborhood,

the specter of poverty is never far in New Orleans. I saw a range of

characters wander in and out of Singleton’s, ranging from the justdown-

on-their-luck to the indigent. All got a kind word from Laura

and sometimes a snack to get them through the day.

Singleton's Mini-Mart

Singleton's Mini-Mart

---

Very early on Saturday mornings, a strip mall parking lot in New Orleans

East, about 20 minutes outside of the city center, transforms

into a bustling morning market. Browsing the stalls are local African

American, African, Mexican and South Asian families who think

nothing of cruising a parking lot at 5 a.m. to get the best produce.

For them, “fresh and local” aren’t gourmet marketing terms. They

simply define what the highest quality and cheapest food is.

Parking spaces overflow with huge bundles of basil, bags of

mung bean sprouts, chayote (or mirlitons as they are called in

New Orleans), cucumber, persimmons, green onions, bitter melon,

steamed buns, chicken over noodles and sweet sticky coconut rice

just packed that morning. There’s a man with eggs, and the chickens

who laid them. And fish, of course — so many fish.

Mary Queen of Vietnam Church, a community gathering place after Hurricane Katrina.

Mary Queen of Vietnam Church, a community gathering place after Hurricane Katrina.

New Orleans East is the Vietnamese community’s historical and

cultural heart. This is where refugee families were hastily settled

after the war, in a public housing complex called the Versailles Arms

Apartments. Those apartments are now boarded up, as families

have been able to buy homes, move into town or join relatives in

other parts of the country. The area is now roughly 33 percent Asian

American and 50 percent African American, with a 26 percent poverty

rate. Many Vietnamese still live nearby and return regularly: The Catholic church and Buddhist temple, the popular Dong Phuong

Bakery and ethnic markets are all there.

The now-shuttered Versailles Arms Apartments in New Orleans East.

The now-shuttered Versailles Arms Apartments in New Orleans East.

Food — and access to nutritious food like the kind sold at the

Saturday market — has always been a priority for the area’s residents,

many of whom lived in multiple refugee camps before settling

in the American South. Leo S. Chiang’s 2009 film, A Village

Called Versailles, depicted this area’s residents finding their political

voice when a post-Katrina landfill threatened to pollute the kitchen

gardens where they grew their food. Food security, defined by the

World Health Organization as “access to sufficient, safe, nutritious

food to maintain a healthy and active life,” is paramount for residents;

that definition also includes access to familiar Asian foods,

freshly grown and free of pollutants.

Xuy En Phan and Joseph Mai in their suburban farm.

Xuy En Phan and Joseph Mai in their suburban farm.

The BP oil spill highlighted the necessity of this local market,

and Versailles-area residents are ramping up food production for

both survival and income. Xuy En Pham and her husband, Joseph

Mai, have attracted local notoriety for turning their entire yard into

a miniature urban farm. Their house on East Lamont Street was so

badly damaged by hurricanes Katrina and Rita that they bulldozed

it, moved in with friends and began to grow vegetables on the land.

After the spill, they lost their jobs shucking oysters for Captain

John’s Seafood, a local restaurant and seafood wholesaler. At that

point, their hobby became a full-time pursuit with the urgency of

finding a job and having something to eat.

Their skill is evident: long, neat rows of kohlrabi, mustard greens,

onion, cucumber and squash. Mai built intricate trellises from discarded

boards and plastic twine, strong enough to support heavy

gourds and squashes. They eat about 70 percent of the vegetables

they grow and sell the rest at the morning market where they make

around $30 to $40 a week.

While they received some relief payments from BP, those ended

in December 2010. From then until the hot day I visited six months

later, nothing. “We need help for living expenses,” Pham said

through a translator. “We need help from BP to live.” The 63-yearold

mother of 10 never stops working as we talk, her smooth skin

and wide smile protected by handkerchiefs and a canvas hat.

Mai and Pham may never be able to reclaim what’s owed to

them by oil companies or the government, but at least they know

where their next meal will come from. It will come from their hands,

their friends and the strained land they have coaxed back into productivity.

This Vietnamese grandmother’s survivalist approach to rebuilding

has inspired other local food- and agriculture-based development

projects. Mary Queen of Vietnam Community Development

Corporation, an economic development group affiliated with Mary

Queen of Vietnam church, is planning an urban farm and landbased

aquaculture fishing project for the community that would

provide jobs and subsistence food for former fishermen as well as

those returning from other parts of the United States after evacuating

the area post-Katrina.

And people are returning. According to a Tulane University

study, Vietnamese New Orleanians had one of the highest rates of

return after Hurricane Katrina among all ethnic groups. Despite the

setbacks, something holds Vietnamese Americans here and gives

them hope for the future. It might be something in the food.

For more information: visit vayla-no.org, mqvncdc.org and

bridgethegulfproject.org.

Nina Kahori Fallenbaum is Hyphen’s food and agriculture editor. She last wrote

about Chinese American groceries in the Arkansas-Mississippi Delta.

Comments