Writer Anabel Mariko Stenzel

I love Japan. As a child, I loved its scenery, food and the cute toys. As an English teacher there after college, I loved its clean streets, work ethic and its generous people. My Japanese mother and grandmother taught me to speak the language and to incorporate being Japanese into my identity.

But one thing I struggled to understand was the resistance to one of modern medicine’s greatest miracles: organ transplantation. As an industrialized nation, Japan has the lowest rate of organ donation in the world.

In 1972, shortly after my twin sister, Isabel Yuriko, and I were born in Los Angeles, we were diagnosed with a genetic disease called cystic fibrosis (CF), which creates an abundance of thick mucus in the lungs and pancreas, leading to malnutrition, pneumonia and lung damage.

Our Japanese mother and German father were both unknowing carriers of the CF gene. One in 25 people of white background is a silent carrier of the CF gene, but it is very rare in Asians. My parents were told that we would be lucky to live 10 years. They were trained to give us daily medications to aid digestion and to administer nebulizer treatments — mist through a breathing machine — several times a day so we could breathe easier. Most challenging was the physical therapy they had to provide three times daily: My sister and I would lie over their laps, and they would pound our chests with their hands to help loosen the thick mucus in our lungs.

These treatments took an enormous toll on our family’s time and my parents’ marriage. But our family persevered. We attended regular school, participated in swim team and Girl Scouts, did chores and brought our breathing machines to our friends’ homes for sleepovers. We even attended Japanese school on Saturdays. I learned to say, “Watashi no seki wa densenbyo janai desu,” or “My cough is not contagious.”

At first, we were shameful and secretive about our illness. But as our disease progressed, we were hospitalized frequently, and the CF became difficult to hide. We found a school system that assisted us when we were hospitalized, and, most significantly, we found compassionate friends who saw beyond our illness. We knew our disease was progressive and carried a high likelihood that we would die young, but we lived with hope and gaman, the Japanese word for perseverance.

Before we knew it, we graduated from high school as valedictorians, moved away to attend Stanford University and pursued graduated degrees at University of California, Berkeley, in the health care field — all with a lung capacity below 40 percent of normal. Thanks to advancements in medical care for CF, we made it to adulthood and witnessed the average life expectancy for CF increase into the late 30s.

In my 20s, my lung damage progressed so severely that I needed oxygen to breathe and required more hospitalizations for aggressive care. I could barely walk and was fatigued and gasping for air constantly. Living away from our parents, Isabel and I spent up to four hours daily doing treatments on each other, pounding each other’s backs morning and night to keep each other alive. At the age of 24, I was offered a lung transplant as a last effort to survive. Four years later, after a rigorous evaluation process and 16 months on the national waiting list, I received a double lung transplant. Isabel, whose disease progressed a bit slower, received her lung transplant at the age of 32. We were finally free from CF.

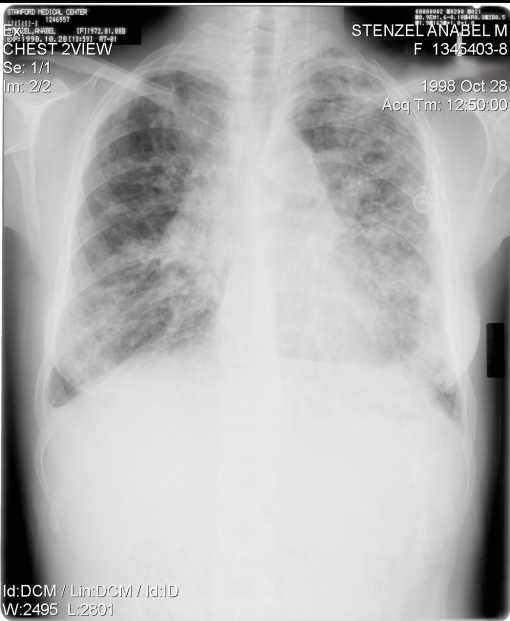

Stenzel’s X-rays before (1998) and after (2009) transplant. White is lung damage; black is air.

For the first time, we could breathe easy, free from coughing, congestion and fatigue. Within months of each of our transplants, we hiked, biked, swam, ran, travelled and even backpacked. We returned to work, me as a genetic counselor and Isabel as a social worker. We were excited to live with exuberance and breathe with gratitude to our donor families.

We wrote these donor families letters of thanks, which were forwarded anonymously through the California Transplant Donor Network, our local organ donation network. Years later, my sister and I both received replies from our donor families, with the rare request to meet. My donor was a 29-year-old man from Oregon who had become brain dead from a brain aneurysm; Isabel’s donor was an 18-year-old Mexican American boy from Fresno, CA, who became brain dead after a car accident. In heartfelt meetings with our donor families, we expressed sorrow for their losses and gratitude that they agreed to donation at a time of personal tragedy so that others could live. Our donors are our heroes.

We became volunteers with the California Transplant Donor Network to educate the public about the benefits of organ donation. We learned that Asian Americans are the ethnic group least likely to donate organs, composing only 2 percent of organ donors nationally. However, Asian Americans make up approximately 6 percent of those on the national waiting list due to the higher prevalence of diseases such as diabetes and hepatitis. With this inequity, our passion to increase awareness about organ donation in the Asian American community was born.

In 2007, we published a memoir, The Power of Two: A Twin Triumph over Cystic Fibrosis, which detailed the lessons learned from living with illness and receiving life-saving lung transplants. This launched us into national book tours and speaking engagements to promote organ donation awareness.

Our memoir was translated into Japanese in 2009, when Japan’s government was debating new laws loosening historic restrictions on organ donation. In the United States, organ donation can only occur when a person is declared brain dead with no chance for recovery. Brain death is death by American (and European) definition.

In Japan, however, death is defined as when the heart dies, not the brain; organ donation is often incorrectly perceived as taking life from the donor. Also, in 1968, Japan witnessed a controversial medical malpractice case involving heart transplantation, so the country has been historically skeptical of organ donation. Other concerns involve Shinto religious beliefs, taboos against touching the deceased body and the concept of ongaishi, or obligation to return a favor, which make the unconditional gift of organ donation hard for many Japanese to fathom. Japanese Buddhists also worry about reincarnation if they are missing organs (though American Buddhists see compassion as the highest virtue, over these concerns, and support organ donation).

In 2009 in the US, 28,000 transplants were performed; 18 people on waiting lists die each day because an organ is not available. In Japan, only 193 transplants were performed in 2009, and 27 people die each day without a transplant. Most transplant candidates in Japan are not offered one by their physicians. Many Japanese pursue transplants abroad by paying for an organ in India or China. Some come to the US, and join our national transplant list to wait, alongside Americans, paying their own money for all medical expenses.

Many Japanese were eager to hear the perspective of transplant recipients around this controversial issue, and we organized a speaking tour through 10 cities in Japan. We educated our audiences while encouraging them to think about organ donation as a humanitarian, spiritual act of helping others, leaving a legacy and saving someone’s life. We were disheartened to learn that antitransplant groups exist in Japan to discourage organ donation and harass families who consent to donate or receive transplants. We learned that the wait time for a kidney transplant in Japan is up to 20 years due to the lack of available donors, compared with five years in the United States.

A documentary film crew, headed by Academy Award-nominated director Marc Smolowitz (The Weather Underground), followed our speaking tour in Japan. The resulting film, also called The Power of Two, illustrates the experience of illness and transplantation in the United States and Japan. It has toured both countries through film festivals and private screenings since 2011 and has won nine awards, including the Audience Choice Award at the 2011 San Diego Asian Film Festival. It will be released in Japanese theaters in 2012.

We hope that sharing our personal story of hope, survival and the miracle of breath will inspire Japanese and other Asians to appreciate the gift of health, educate themselves about organ donation and, most of all, consider signing up to be organ donors. Some people don’t like to think about organ donation because they don’t want to think about death or tragedy. They fear discussing death will bring bad luck. We wish no one suffers tragedies to become organ donors, but, unfortunately, accidents happen. Being an organ donor is a valiant way of showing compassion to those most in need.

Since a new organ donation law was enacted in Japan in 2010, over 30 Japanese families have agreed to organ donation. Here in the United States, I hope that someday the number of Asian American organ donors will approach the number of Asian Americans on the waiting list, and decrease the discrepancy. Change is happening.

Anabel Mariko Stenzel, 40, is an author and patient advocate from Redwood City, CA. She works as a genetic counselor at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, helping families impacted by genetic disease, and serves as a board member of Cystic Fibrosis Research Inc.

See the official theatrical trailer of The Power Of Two:

Comments