Written by Toshio Meronek

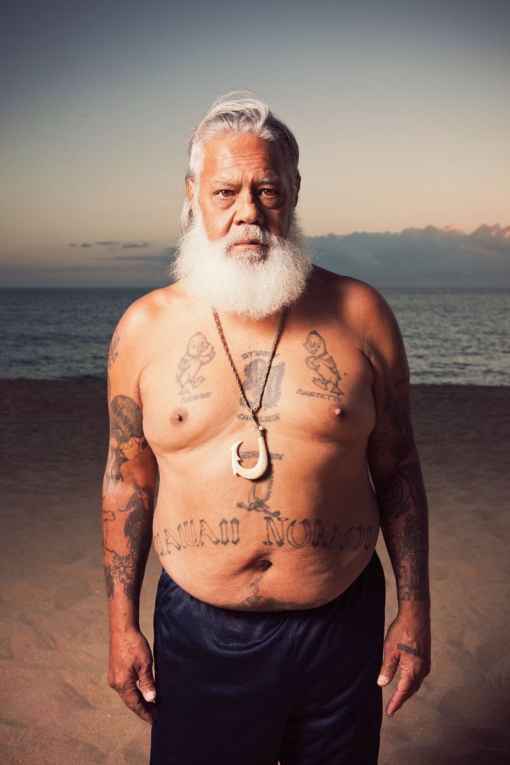

In the mid-1970s, Delbert Wakinekona became a local celebrity in Hawaii. Convicted of murder, he escaped not once, but twice from Halawa State Prison on Oahu. “They catch me about six months later, they take me back to prison and hook up high security: closed-circuit TV, electric doors,” he says.

After the first escape, the governor declared on television: “Wakinekona will never escape again from there.” Months later, he escaped. Again.

Wakinekona’s reputation as a troublemaker grew after he began sneaking information about poor prison conditions to a local TV news reporter. “The governor got mad and made it a priority to get me out of the state of Hawaii,” he says. That’s how, in 1976, he became one of a handful of Hawaiians imprisoned out of state.

Since then, that number has swelled to around 2,000, as Hawaii has increasingly outsourced its prison services to private corporations thousands of miles away in an effort to lower its own incarceration costs. Saguaro Correctional Center in Eloy, Arizona, operated by the Corrections Corporation of America, now houses more Hawaiian prisoners than any other prison in the nation — including those in Hawaii.

Inmates like Wakinekona end up paying the difference — in severed family ties, lost cultural identity and debilitating health problems. In 2011, Gov. Neil Abercrombie promised to bring all Hawaiian prisoners back to the islands, but whether the government will actually follow through on reforming a prison system that is notoriously plagued by abuse and lacking in transparency remains to be seen.

In the meantime, Wakinekona and others are attempting reforms on the ground, hoping to make mainland prisons more like home by incorporating cultural programs and creating transition centers to help the inmates reacclimate to life on the islands.

Illustration by Chris Danger

OUTSIDE APPEARANCES

Over the phone, Wakinekona is soft-spoken and, predictably, sounds worn out from 41 years spent in Hawaii, California and Arizona prisons, plagued by the hepatitis C and liver problems that have repeatedly threatened his life.

Growing up poor in Oahu’s western Leeward Coast, he was no stranger to brushes with the law. Though it’s only 25 miles from Waikiki Beach, this majority Native Hawaiian area is largely tourist-scarce and home to many of the state’s poor and homeless.

In 1970, Wakinekona was sentenced to life without parole when a botched grocery store robbery resulted in a man’s death. (He maintains his innocence.) It took awhile for reality to set in.

“They give you a bed,” he says. “You go to sleep, and you get up. [Around the six-month mark,] I realize, wow, I’m going to do this for the rest of my life.”

Wakinekona’s voice cracks when he talks about his kids during this time. “Knowing you got a family on the streets is kind of hard for a man behind walls to accept,” he says. His four children, ages 1 through 5, would grow up with little contact with their father.

There is a reasonable chance that, had Wakinekona been white, Chinese, Korean or virtually any other ethnicity, he would have received a lesser sentence. According to a 2010 study by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Native Hawaiians are three times more likely than whites to be incarcerated for the same crimes and tend to receive harsher sentences.

They also comprise 40 percent of all prisoners in Hawaii despite making up just 24 percent of the overall population. On the mainland, the racial makeup of prison populations is similarly out of sync, with blacks, Latinos and other historically disadvantaged groups exceedingly overrepresented.

RaeDeen Karasuda, a senior researcher at Kamehameha Schools, which specializes in Native Hawaiian language and culture, says race is a “huge question” with regard to who gets locked up. There’s a stereotype dating back to the late-1800s takeover of Hawaii by the United States, she says, of native Hawaiians being “poor and angry, so people make the immediate leap to criminal identity.”

When Wakinekona was transferred to Folsom State Prison in California in 1976, he found that his reputation as “the most baddest and dangerous inmate that ever came out of the Hawaiian penal system” had preceded him. The staff told Wakinekona: “When you came up, we had posters of you. Everybody thought you was about 7 feet tall.”

Wakinekona wasn’t as tough as the rumors claimed. He had trouble adjusting to the prison culture of the mainland. He desperately wanted to return to Hawaii, where contact with his family would be easier, the spiritual connection to the islands experienced by many Native Hawaiians would be more intact and where he would be able to take classes in mechanics, painting, welding and woodworking from behind bars. Folsom, like many other prisons, didn’t offer such programming.

By 1983, Wakinekona had had enough. He sued for the right to return to Hawaii, making national news when his case, the first to challenge the transfer of prisoners across state lines, made it all the way to the Supreme Court.

In a 6-to-3 decision, the court ruled against Wakinekona, setting a precedent that today allows economically hard-up towns in states like Kentucky and Michigan to capitalize on the overcrowding of prisons in far-flung places like Hawaii. In his dissenting opinion, Justice Thurgood Marshall said the mainland transfer:

“represents a substantial qualitative change in the conditions of his confinement. In addition to being incarcerated… Wakinekona has in effect been banished from his home, a punishment historically considered to be ‘among the severest.’ For an indeterminate period of time, possibly the rest of his life, nearly 2,500 miles of ocean will separate him from his family and friends....Surely the isolation imposed on him by the transfer is far more drastic than that which normally accompanies imprisonment.”

The 1990s and 2000s saw a boom in cross-border incarceration. Although California and Idaho still ship prisoners elsewhere, “Hawaii is alone in doing this deliberately, at such a scale, and for so long,” according to Peter Wagner, executive director of the criminal justice policy think tank Prison Policy Initiative.

The practice is meant for long-term prisoners, like Wakinekona, and so in 2006, a round of prison consolidation landed him in Eloy, AZ, a desert prison town so isolated that it was like its own sweltering version of a Hawaiian island. Eloy’s economic bread-and-butter is incarceration, and it houses a third of Hawaii’s prison population in two facilities built specifically for imported prisoners: Red Rock and Saguaro Correctional (the latter is exclusively Hawaiian).

A half-square-mile of blazing concrete surrounded by sand, saguaro cactuses and gila monsters is home to 1,700 Hawaiian inmates — and the largest concentration of Native Hawaiians outside of Hawaii, according to Wagner. Non-native Hawaiians are incarcerated here in large numbers, as well.

By the time Wakinekona arrived at Eloy, his relationship with his wife had deteriorated, and he had lost touch with his children. When he set foot on the mainland, seeing them at all became out of the question. He found that many prisoners at Eloy were in the same boat. They had little, if any, contact from their loved ones and few rehabilitative opportunities.

At Eloy, he met Kaiana Haili, a Native Hawaiian religious practitioner who has made it his mission to serve this overlooked populace. For the past 11 years, in advance of makahiki, the Hawaiian New Year and harvest season, he imports hundreds of pounds of tropical foliage, brightening the stark desert landscape with kukui nuts and ti and maile plants.

For a few short days, momentarily festive Hawaiian prisoners trade in their orange jumpsuits or tan uniforms for kihei and malo (traditional capes and thongs). Along with weekly classes in their native language, hula, chant and ceremonies and rituals, the program he founded aims to help the men — whom he calls his incarcerated koa (warriors) — rediscover their ancestral traditions.

It also helps, he believes, with their spiritual recovery and rehabilitation. At the very least, Wakinekona says, some of the programming gives participants “the foundation of our kupuna [elders] — dignity, loyalty, respect and honor.”

Haili’s ceremonies are often covered by local media, which has “created a false sense of true change happening in our prisons,” Haili says.

The Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), which operates Red Rock, Saguaro and 60 other facilities and is the largest private corrections company in the United States, has been less than supportive of his efforts, he says, even as it has reaped positive publicity from the cultural programming.

After a decade, Haili’s practices are still treated with skepticism by prison authorities and classified under the category of “new or unfamiliar religion.” Wakinekona, a member of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement who considers Hawaii to be its own nation occupied by the United States, is particularly critical of how watered down many of the cultural practices became in order to get approval, taking issue with makahiki and other practices being treated as occasional religious rituals rather than as part of the Hawaiian way of life.

In reality, the program can only do so much for inmates. CCA-administered prisons have a shameful record of mistreating prisoners and, kukui nut necklaces notwithstanding, Hawaiians are no exception. CCA’s Otter Creek Correctional Center in Kentucky housed much of Hawaii’s female prisoner population until 2009, when a sex abuse scandal implicating prison staff sparked Hawaii to cut ties with the facility and bring all 168 of its women prisoners back to the islands.

More recently in Arizona, guards have received probation for allegedly banging prisoners’ heads on tabletops and forcing oral sex upon them. According to one 2012 lawsuit brought by five Saguaro prisoners, a guard allegedly threatened an inmate by saying: “We will continue to beat you and the only way to stop that is to commit suicide.”

This year, the families of two Hawaiian men killed by fellow prisoners at Saguaro have filed separate lawsuits citing similar problems, such as “negligence, recklessness and a flagrant failure to protect.”

Kat Brady of the justice reform-focused Community Alliance on Prisons has long been fighting for better treatment of native prisoners.

“The difference between indigenous justice and Western justice is with indigenous justice, you were always offered a chance at redemption. You could be forgiven, get your slate wiped clean and start over. With Western justice, you never, ever get out,” Brady says.

The growth of private companies like CCA, which by its own count is responsible for more than 80,000 prisoners in 19 states and Washington, DC, “has been devastating, because we’re dealing with corporations who only care about the bottom line. It’s about keeping the beds warm and the money flowing,” Brady says.

Most advocates agree that families are hurt the most by the outsourcing of prison services. Most of the Hawaiians imprisoned in Arizona can’t afford the $2,000-plus it would cost to fly to the desert and lodge a partner and kids. So, while CCA allows each prisoner to have an unlimited amount of approved visits, that privilege is lost to most of Saguaro’s inmates.

When Wakinekona’s mother died while he was in jail, he was told he could only return to Hawaii if he paid the passage of two prison guards to accompany him — an economically prohibitive policy to anyone imprisoned outside of their home state.

CCA does have a videoconference visitation program, but it’s only available on a case-by-case basis (you have to apply and be approved) at a maximum of twice per month.

Roy Yamamoto, a former Saguaro inmate turned pastor with New Hope Ministry — which offers religious services to Saguaro prisoners — has witnessed firsthand the heartbreaking effects of these limitations. Watching kids in Hawaii videoconference with their imprisoned parents, he was moved to see some of the children kiss the screen when their father’s face appeared on the monitor.

Delbert Wakinekona on the beach outside his home on the west coast of Oahu. Photograph by Marco Garcia.

A GLIMMER OF HOPE

In 2010, Gov. Neil Abercrombie made a promise to bring back all of Hawaii’s prisoners, across the 3,000 miles, permanently. “It costs money. It costs lives. It costs communities,” he says. “It destroys families. It is dysfunctional all the way around — socially, economically, politically and morally.”

But six months later, with no plan in place to fulfill his promise, he approved a $136.5 million contract to keep prisoners at the CCA facilities for three more years.

“Yes, it’s a nice thing to bring them back,” says Barb Marumoto, a Republican legislator in Oahu who has visited women’s prisons in Hawaii. “But the question is: Can we afford it?”

The Hawaiian Department of Public Safety, which administers the state’s prisons, says yes. This year, it unveiled a plan to bring back all of Hawaii’s prisoners by 2015 through early release programs, hiring more probation officers, opening new prisons on the Big Island and Maui and reopening a currently closed facility. But, Marumoto remains hung up on expense: It costs $128 per day to imprison someone on the islands versus $76 in Arizona, according to the Department of Public Safety.

The economic argument for sending prisoners out of state doesn’t hold up, says a Hawaiian parole officer who prefers not to be named. “It’s myopic,” he says. “It might be cheaper now, but we lose money in the long run.” Over the years, the taxes and prison-related jobs that stay in Hawaii keep more local dollars in the islands, many have argued.

Meanwhile, Brady’s Community Alliance on Prisons, as well as mainland organizations like Critical Resistance, in Oakland, CA, and the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana, in New Orleans, are pushing to refocus governmental budgets away from incarceration and toward social services like health care and education, which they say result in fewer convictions.

Roy Yamamoto, the former Saguaro inmate turned pastor, says Hawaii is “home and family,” but notes that moving all prisoners back to Hawaii isn’t a perfect solution. Hawaiian prisons have a long way to go in terms of offering the kind of “faith-based programs and better food” that CCA provides.

“Justice reinvestment” is the term activists use to describe moves they believe will cut prison and probation times. In Hawaii, according to a study by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance and the Pew Center on the States, that means (among other things) cutting pre-trial delays and giving certain “low-risk offenders” parole rather than jail time.

Hawaii isn’t the only state considering similar prison reforms. California, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, facing pressure from inmate advocates and finding the difficulty in oversight to be problematic, brought or are in the process of bringing their prisoners back from out of state.

IN SICKNESS AND IN HEALTH

In May 2011, Wakinekona’s “asthma” was getting the best of him. When he entered prison, he says, he weighed about 240 pounds. By last year, he’d lost half of it. He’d been to the medical unit several times in the past month complaining of feeling “submerged underwater.”

One day, as he was leaving his cell, he suddenly experienced pain so intense, he figured it was his time to go. After other prisoners alerted a guard, he was sent to surgery where doctors removed over a gallon of fluids from his stomach that his kidneys and liver had been unable to process. “You’re lucky you came in time,” they told him.

Wakinekona’s friends on the outside got word of his surgery. A woman named Lillian Harwood (who met Wakinekona while she was working at Saguaro as a minister and teacher) and a retired attorney named Robert Merce teamed up with the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting indigenous Hawaiian culture, and pressed Wakinekona to try for a “compassionate release.” This, if granted, would mean that the state would acknowledge his time served and the inability of the prison to provide adequate medical care.

“I promised Wakinekona he would not die on foreign soil behind walls — that he could at least touch his homeland” before he passed, Harwood says.

Wakinekona was skeptical but he let them try for his release. On Oct. 28, 2011, 68-year-old Wakinekona, who had spent 41 years in prison, was free. Six days later, Wakinekona and Harwood married.

FAMILY TIES

Most prisoners will eventually re-enter society, but their chances of recidivism, or going back to prison, remain high. The Minnesota Department of Corrections surveyed the major studies on recidivism last year and wrote in a report: “Decades of research indicate that visits from family improve institutional behavior and lower the likelihood of recidivism for inmates.”

While a locally focused joint study from the University of Hawaii and the state’s attorney general didn’t find a statistically significant difference between recidivism rates for prisoners in Hawaiian prisons and those on the mainland, many reformists argue that contact with family makes a huge, positive impact. As Kat Brady puts it: “How do you reintegrate someone who hasn’t seen their families in five or 10 years?”

By the time Wakinekona was released, he hadn’t seen his family in four decades. “I still have grandkids I haven’t met, but they call me, and they have children of they own,” he says. He is touched that his grandchildren still recognize him as part of the family, despite the fact that he wasn’t there for them growing up. Harwood argues that the kids “were punished equally” by the lack of contact over the decades.

Wakinekona now lives with Harwood in Makaha, about a 10-minute car ride from where he was originally arrested in the ’70s. Being outside has been a tough adjustment for him. Like many formerly incarcerated, he came out worse for the wear.

“I walk around with a big lump inside my pants,” he jokes, referring to his 22-by-29-inch hernia. Because of his record, he’s not eligible for Social Security, so his health problems are a big-budget item for the new family.

Wakinekona still worries about the other prisoners. He believes conditions are getting worse for prisoners nationwide. “In Hawaii in the 1970s, I thought we was behind the times, but today, they don’t have nothing,” he says.

Since he entered prison, education programs inside have been cut. Arizona now taxes commissary items and last year started charging visitors a $25 “background check fee.” Across the nation, prisons are extremely overcrowded; the latest numbers from the U.S. General Accountability Office estimate that federal prisons were 39 percent above capacity in 2011 (a number it expects to balloon to 45 percent by 2018).

Aside from the conditions inside, Harwood says private prisons like CCA’s are also particularly lacking in transparency (“Even the governor of Arizona cannot go into [Saguaro] without clearance”), and that she’s been blacklisted from entering the prison after she smuggled out documents to the lawyers of men incarcerated there. Many of the men’s lawyers are Hawaiian and not licensed in Arizona, adding another layer of complication.

Now she and Wakinekona spend their days advocating for prison reform. They supported a bill that would have freed disabled and ill prisoners, but it failed. Another project they fought for has met with greater success. The Hawaii legislature recently ordered the Department of Public Safety to draw up plans for a pu’uhonua, or “wellness center,” where prisoners can transition back into society and become self-sustainable by, among other things, learning to grow taro and raising fish, with easier access to family than if they were imprisoned on the mainland.

For now, the 1,700 Native Hawaiian men still in Arizona have a long wait before they can trade in Eloy’s desert sands for Hawaii’s tropical foliage. Hawaii’s previous governor, Linda Lingle — who initiated the big mainland prison contracts in the early 2000s — recently lost her bid for a seat in the Senate. CCA’s lobbyist in Hawaii attends most Department of Public Safety meetings, and the company won’t likely give up such a lucrative contract without a fight.

It’s an uphill struggle against big business and slow bureaucracy, but Wakinekona and Harwood are married to the cause. They continue to work on the pu’uhonua, hoping that if and when the men do finally come back, the wellness center will be waiting for them, ready to, in Harwood’s words, “bring healing and closure to a broken past.”

Toshio Meronek is a freelance writer focusing on social justice, prisons and LGBT/ queer issues. His work has appeared in Dwell, In These Times, ReadyMade, SF Weekly and Truthout, and he is a regular contributor to The Huffington Post. This story was funded in part by the Spot.Us community.

Comments