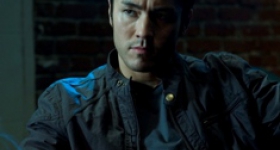

Photo courtesy of IFC Films

When Mira Nair set out to make a film about post-9/11 New York City, her aim was simple, though her approach was not. The India-born director already had several noteworthy titles under her belt, including 1991’s Mississippi Masala, 2001’s Monsoon Wedding, and 2006’s epic coming-of-age story starring Kal Penn, The Namesake -- and yet, she was still finding trouble getting the industry behind her latest project.

“When I approached people with my idea, I was told that I would have to make the film at most for $2 million because I had a Muslim protagonist, and I should just shoot it in Rockaway [Queens],” she told the audience at a Tribeca Talks event opposite Bryce Dallas Howard at last month’s Tribeca Film Festival. “[So] I didn’t go to the studios. And the trouble is, we only think there’s one way. But there isn’t. There are many other ways. But they’re damned difficult.”

“I have this weird thing with rejection,” Nair continued with a laugh. “I just want to prove them wrong.”

The story Nair wanted to tell with her new film, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, was an important one, she said, and that’s why she put up with three years of adapting the manuscript to screenplay (from Mohsin Hamid’s novel of the same name) and two years of fundraising in order to even begin the process of filming.

Fundamentalist tells the tale of Pakistani protagonist Changez (played expertly by Riz Ahmed), a savvy-yet-earnest young man who makes his way from the streets of Lahore, Pakistan, to Princeton University in pursuit of the American Dream. His quick wit and intelligence help him to rise quickly in the ranks of Wall Street after being recruited by financial hot shot Jim (Kiefer Sutherland), and for a while, he’s living an enviable life -- buoyed by an impressive paycheck, increasingly exclusive social circles, and an artsy girlfriend (Kate Hudson).

But then 9/11 happens, and Changez’s life begins to unravel as he grapples with the realities of being an “other” in a country that had become his home. There are uncomfortable scenes (one in which Changez is ordered to strip completely for customs officials is particularly demeaning) and some all-too-familiar instances of exoticism. Overall, however, Nair’s aim is not just to highlight post-9/11 injustices, but also to understand the interconnected web of cause-and-effect that creates that “otherness” divide.

Other films that have tried to capture the feel of New York City post-9/11 have fallen short, Nair added, because the way the narratives are presented, “it’s not a conversation, it’s a monologue. I wanted to create something modern, a dialogue about 9/11.”

“I always want to answer the question, ‘Who is the other?’ and make that ‘other’ palpable,” Nair explained. “And in light of the kind of danger we live in, it’s about time we start knowing each other.”

Nair herself moved to the States at the young age of 18 after, she claimed, she watched 1970’s Love Story for the first time and thought that Harvard looked “rich enough to give me money.” So she went to Harvard, majoring in documentary filmmaking. After graduation, she moved to New York City, where she spent five years living in Harlem, selling African art and waitressing to get by, making documentary films on the side. But that period was “lonely,” Nair said, because there wasn’t yet an audience for the kind of films she was creating.

“It wasn’t Bollywood films I was making, and India was still relatively unknown to the States; it was still foreign,” she said. “And I felt caught in-between, having to explain my culture to people who already had an idea of India in their heads.” She recounted once having to explain her cultural upbringing to several women at a dinner party.

“[I told them], ‘Well, I’ll send the elephant to the airport when you come. And [then] I’ll take you to my treehouse,’” she joked to the women, who took her words at face value.

But it was instances like this that drove her to continue making films about her own culture, bridging the gap between ignorance and knowledge, “other” and “one of us.” And her work began to pay off.

“You pursue something without even knowing that you have any fruit at the end of it, or an audience,” she explained. “It really humbled me, when Salaam Bombay came out, or Mississippi Masala came out, that there were lines around the block of hybrid people, multicolored people, finding themselves on screen, pretty much for the first time. That’s pretty powerful, for what we do… how many people we reach with this amazing medium.”

Comments