…lynching and empire were bitter fruits of the same tree.

—Nerissa S. Balce

In 1898, Tampa, Florida, a group of drunken American soldiers used a child for target practice. The soldiers were white. The child was black.

*

The Lost Bar is four blocks from my door and has quality bourbon, whiskey, and the like for cheap. I'm a new resident in Philadelphia. It's Friday night and packed. As usual, the crowd is all white. NFL pre-season is on both screens. I'm trying not to think about recent news: the violence in Gaza, Eric Garner killed by police in Staten Island, Michael Brown killed by police in Ferguson. Maybe the biggest collaboration in failure between me and my formal education has been the belief that I am apart from history and history is apart from me. I have no interest in digging up ghosts. I don't need to. They follow me. When the bartender asks if he can help me, I request my drink in impeccable English, and maybe I turn the Jersey volume up in my sentence. I wonder if the two men to my left with thick forearms (and necks to match) hear me say, "Rye, neat. And a glass of water, no ice."

*

That summer when U.S. regiments were making camp throughout the Southeast for several weeks, they were en route to fight the Spanish in Puerto Rico and Cuba. And you can imagine how tense it got in those deeply segregated towns when among the troops were the hundreds of black soldiers from the 24th and 25th Infantries and the Ninth and Tenth Cavalries -- Buffalo soldiers. Many, if not the majority, of the black troops had spent most of their time in the North and so were accustomed to doing business with local restaurants and shops. One black soldier, according to historian Willard B. Gatewood, reported his experience in a letter to a friend: "Prejudice reigns supreme here against the colored troops. Every little thing that is done here is chronicled as Negro brazeniness [sic], outlawry, etc. An ordinary drunk brings forth scare headlines in the dailies." [1]

This went on, escalating for weeks, until a white soldier, a member of the Ohio Volunteers, snatched the black child from his mother and held him upside down by the ankle, spanking him with his free hand. The Ohio servicemen then decided a contest was a good opportunity to show off their marksmanship. The winner would be the one to shoot through the child's sleeve. Hard to say how many rounds they fired, but accounts say they had their "fun" and finally released the child, who was, according to available sources, physically unharmed. With outrage brewing for weeks, the incident sparked race riots in Tampa proper, not to mention the military encampments themselves. The local news reported, "[T]wenty-seven black troops and several white Georgia volunteers from Tampa, all with serious wounds…were transferred to Fort McPherson near Atlanta."[2] The day after the bloody scuffles erupted, the soldiers, black and white, were deployed to Cuba. They were being sent to fight for American expansionism in the Caribbean and beyond. Expanding the borders of America, however, also meant the expansion of military occupation and racial segregation.

*

I moved to an old textile and ribbon factory in the Kensington section of Philly two months ago. The anti-Catholic "Nativist Riots" were here in the summer of 1844. Now, galleries, cafes, and vegan options have popped up for the new young white professionals and artists who have moved in. Much of the neighborhood is still working class Irish. The spire of St. Michael's sits in my second-floor window.

My first few weeks here, at another bar farther down Frankford, one long-time resident sitting next to me told me, with a touch of brogue, "This neighborhood is going through changes. A few years ago, me and you couldn't walk outside on this street together." He paused and gave me a hard look, a lot like a kid who, unprovoked, snarled at me and gave me the finger earlier today. "I hope you enjoy living here." I'm cursed: everywhere I go, no matter what corner or room or stairway, I get this feeling, this pulse of history, like the place is throbbing with what used to be here, though I can't always name it. And what used to be here often echoes exactly what still is.

Tonight, on the TV at the Lost Bar, the Eagles turn the ball over in their own territory and the Patriots take over. I down my rye, leave the water, and go home.

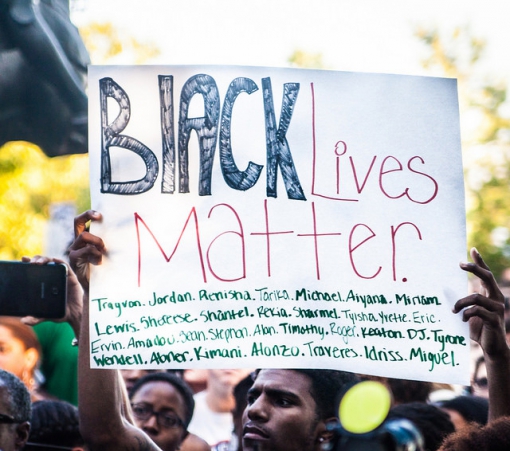

Image by Mikael Owunna

Before Michael Brown, before Kimani Gray, before Oscar Grant, before Sean Bell, I've wanted know: How does a state justify the killing of black men and boys? I don't have a better answer than, they just do. They justified it in Tampa in 1898. They justified it for 300 years in America before that. They justified it for more than a hundred years since, in L.A., Chicago, Philadelphia, New York, Ferguson, Detroit, Oakland, New Orleans. Every time I start the catalog, I know I could go on a long time. I'm afraid if I open my mouth, the litany won't stop.

*

There's this story I want to tell about how Filipinos in a town called Balangiga were fed up.

U.S. soldiers had come to occupy the town, and before long, they rounded up dozens of Balangiga men, commanding them to chop down edible crops, which the military called weeds, growing around their huts. After a long day's labor the Filipino men were forced to sleep, not at home with their families, but in groups of four dozen in a single Silbey tent designed for six men to lie down, which meant they slept sitting up. There was also more than one allegation that an American soldier had raped a woman from Balangiga. And on top of all of that, the townspeople just didn't want the Americans there.

So, one night, several Filipino men dressed like women and carried a number of undersized coffins to the town church. When American guards stopped the cross-dressed men, they told the Filipinos in disguise to open the coffins. Inside, the sentries saw the actual corpses of children. But also hidden in the boxes were the blades the men would hand out to other men gathering at the church. The Filipinos told the guards that the children had died from cholera, which startled the Americans and cut the impromptu investigation short. The mourners were told to carry on.

Despite being at a severe disadvantage in weaponry, the Filipinos attacked before dawn and chased the Americans out, killing close to fifty marines using mostly just machetes. It was the bloodiest single skirmish suffered by American forces during the Philippine-American War.

"Occupied territory is occupied territory, even though it be found in that New World which the Europeans conquered," writes James Baldwin, "and it is axiomatic, in occupied territory, that any act of resistance, even though it be executed by a child, be answered at once, and with the full weight of the occupying forces." In response to the battle at Balangiga, General Jacob Smith immediately ordered his marines to return and kill every Filipino over the age of ten and to turn the landscape into "a howling wilderness."

*

Today, I'm in a cafe to write my way through this essay, and a tall, thin, white man probably in his twenties works in the kitchen. His scruff grows around a narrow chin. His hair is pulled up into a short ponytail. When he turns around, I can see his t-shirt for the heavy metal band, Dead Child. I can see him draw the knife to chop the vegetables, assemble a new sandwich, and wipe down the chopping board.

Here's what it's like to be Filipino and curious about history. Most everything you see in your daily life, including what ends up in the news or in books or on social media or in the songs and diatribes of white people, has a second story. How often I enter a room and that story seems to have never been told. Or the story is finally read but with utter disbelief. Or irony. Or pity. I am at once amazed at the complexity and multiplicity of this country's history and at the same time exhausted -- and sometimes devastated -- by having to walk among white people as if I haven't witnessed something that they haven't seen yet. I watch the video of a boy shot by police at Fruitvale Station or a man strangled by police in New York. Sometimes I see a brick wall in northeast Philadelphia with a giant confederate flag painted on it or I see something simple as a concert t-shirt. Did any of it happen? Is it really there? Like a mad man. I feel like a mad man. Or I feel like I'm not a man at all.

I've had to hone my seeing twice, like most people of color, but I want to be clear that I have never been at risk the way that Michael Brown was at risk or the way other young African American men have been and continue to be at risk. The fact that I can choose to name what I see already eases me out of a danger that Michael Brown, at the hands of police power, couldn't escape. But I am directly descended from people who were named savage, criminal, bandit, freak, expendable. It was one hundred fifteen years ago a representative of the state held a black child upside down so other representatives of the state could shoot at him.

I would argue that in one hundred and fifteen years, the state has not changed the way it turns a man or woman into an animal in order to justify its own brutality.

*

A child snatched from a mother and gleefully fired upon by a group of drunken soldiers, the casual order to slaughter anybody over the age of ten, an eighteen-year-old gunned down by some half dozen bullets at close range -- these are by no means equivalent horrors. But they do make a nation of ghosts. Those ghosts are made citizens of a bloody country by the charters of American silence. Those ghosts knock on my door. They talk to me when I'm awake and when I sleep. When I study history, I'm studying where the ghosts come from. I'm looking for their names. I'm looking for evidence of their bodies. When I, as a poet, study history, I'm calling the ghosts to come closer. And I've promised, when they don't approach, I will go to them.

[1] Gatewood, Willard B., Jr. "Negro Troops In Florida." The Florida Historical Quarterly 49.1 (1970), p. 4.

[2] Gatewood, p. 9.

***

Patrick Rosal is a former Fulbright Fellow to the Philippines and the author of three books of poetry, most recently Boneshepherds. His essays have appeared in Grantland, Los Angeles Review of Books, Drunken Boat, and The New York Times, and his poems have appeared in Tin House, Gulf Coast, Harvard Review, American Poetry Review, and elsewhere. He is a full-time faculty member of the Rutgers-Camden MFA program.

Comments