This is the second in a series of profiles of prominent Asian American women for Women's History Month. Stay tuned for more!

Although runway shows are painful for me to watch (the models always look like they're going to fall over and snap a limb) I have to appreciate the simplicity, drape, and unexpected color of Doo-Ri Chung's doo.ri designs (love the green gloves in the vid above!) In late years Asian Americans have popped up more and more in the fashion world, and I could choose a designer to profile almost at random. But the way the media handles Chung's immigrant-family story is fascinating, and illuminating.

The most popular touch-points of her bio are that she started her design business in the basement of her parents' New Jersey dry-cleaners, and that she apprenticed for six years with Geoffrey Beene. Yes, that's the conservative suits and preppy-wear guy; presumably, it's the rise of a cutting-edge fashion-head out of that welter of dowdy conservatism that arouses media interest in that detail. In fact, that seems to be the point of drilling into both of those items: a fashion designer springs out of lumpen dowdiness. The Asian immigrant dry-cleaners are the direct descendants of the Chinese laundryman stereotype that dates back to the Gold Rush era. It's a delightful story that one of the designers who determines what is "fashion forward" descends -- genetically, geographically, and logistically -- from America's most fobby and fashion backward business model.

Yet, in the documentary, Seamless (which followed three contestants for the CFDA/Vogue design awards, and which you can watch here if you have netflix -- and while you're at it, please note the number of Asian American designers among the ten finalists!) a montage in the first two minutes of the documentary makes clear that all young designers start their design businesses in weird spaces: living rooms, bedrooms, crappy little lower east side apartments. And some even, horror of horrors, get help from their mothers! Chung's section of the doc shows the basement of her parents' dry-cleaner (appropriately named "Paragon") to be a bright, airy, loft-like space that wouldn't shame any creative hipster with a material practice. Indeed, it is Chung herself who, perhaps pragmatically, helps the narrative along; early on she states flatly, "It's the total immigrant story," relying on the dry cleaners and the parents to fill in the rest.

And that's another point which deserves unpicking: Chung and the filmmakers make it clear how much help she gets from her parents. Her father carries and delivers samples; her mother sweatshops zippers and other straightforward seamstress duties. While one of her judges calls her a "one man show," who does everything herself, we see the other contestants working with in-house hands while Chung has to outsource her sample sewing work to Korean tailors -- presumably found through her family's network.

Chung doesn't go into the details of the business end, but it shouldn't be too much of a stretch to imagine that she's also gotten help with her finances and her business model from parents who've been running a successful small business for 24 years. And, yes, her parents' savings helped fund her start-up. This contrasts starkly with the other two profiles in the film: Prouenza Schouler, two 26-year-old Parsons prodigies, whose senior project was bought by Barney's and have been running a seat-of-their-pants business without assistance ever since; and Cloak, a menswear concern run by a Russian designer alone in NY without even the support of his long-distance wife.

A media always looking for a hard-knock story to fulfill our expectations thought it had found it in Chung. But the real story has to be more complex than that. The "real" story includes Chung's studies at the prestigious Parsons school of design, and the fact that one of her designs was spotted by Beene while she was still a student there. She became his assistant, and then his head designer, helped along by a key employee leaving early in her tenure, and then left to start her own business in Manhattan with a friend in 2001. When the partnership split up, Chung opened a store in SoHo, selling exclusively her own designs, only to close it again a year later to concentrate on selling her line, Doo.ri, wholesale, because she hated retail.

Thus began her "reverse commute" from her apartment in Chelsea to her studio space in Paragon's basement in New Jersey. (That's right, she went back to New Jersey.) Her first show in 2004 resulted in some big-time orders, among them Henri Bendel. But it was her participation in the CFDA contest in 2004, and the exposure the 2005 documentary brought to her, that really launched her career: she finally found a financial backer, and was able to move out of the dry cleaning basement in New Jersey and (back) into Manhattan.

In 2006 she did end up winning the CFDA award, two years after her first outing in the documentary. Since then she's become increasingly establishment, branching out into resort wear, shoes, jewelry, handbags, hosiery. Last year she launched a new, lower priced line called Under.Ligne (which you can shop online here.)

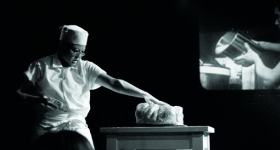

Much more interesting than the tired immigrant trope (and the more ordinary design school-failed business-award win-explosion of popularity story) is the fact that Chung works "old school," by draping fabric over a dressmaker's dummy to see how it looks, rather than by designing on paper first. The technique speaks to how she first made her name with innovatively draped jersey on evening wear, before moving on to more stiff constructions in suiting and day wear. In the media, she frequently, albeit vaguely, credits her "background" for some of her design elements, but the drapery and the jersey she's famous for is resolutely Western.

Her takeaway from her six years with Beene could be culled from an artistic apprenticeship in any discipline, from dance to filmmaking: "... there's discipline required -- knowing that there is this monotony of business that interferes with the creative process, and you need to establish a routine to tackle those things before they take away from your creative process. ... after production you get this one moment of time where you actually get to be creative. And it's that 8% of everything you do that inspires you, what drives you."

Comments