By Chuleenan Svetvilas

On November 21, 2004, Chai Vang, a Hmong American, was out hunting for deer in the woods of Wisconsin and ventured onto private property. He was told to leave by one of the landowners but this encounter ended in a violent confrontation, in which Vang shot eight white people (only one of whom had a gun), killing six. The shocking deaths and Vang’s subsequent trial in 2005 spurred a media frenzy, which immediately captured the attention of Minneapolis filmmaker Mark Tang, whose company Passion Fruitfilms has made many films about Asian Americans.

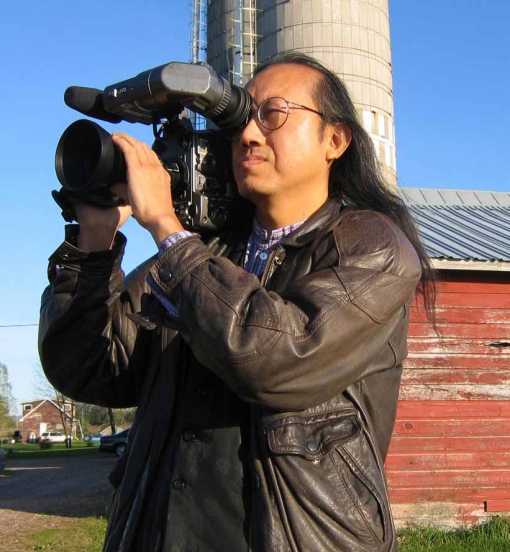

Co-director Mark Tang

“I felt at that time, it’s not very good for the community,” says Tang. “There needs to be more in-depth investigation of this thing, not just sound bites. But I didn’t really want to do it because I’m not Hmong. I’m Chinese, you know and this is their story.” Then Tang talked to some Hmong filmmakers and discovered that they weren’t ready to embark on such a project. He decided to take the plunge and later brought on board Lu Lippold, co-director of Wellstone!, as co-director. “I needed another set of eyes to really strike a balance,” says Tang. “Here we have one of the most difficult cases for people of color. A person of color is not the victim [but] a perpetrator. It’s almost like the reverse of the Vincent Chin case.”

Co-director Lu Lippold

Hyphen spoke with the directors when they were in San Francisco for the screening of Open Season at the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival. The fascinating documentary, which includes riveting courtroom testimony, carefully tells both sides of the story -- that of Chai Vang, who claimed the shooting was self-defense because he was racially harassed and prevented from leaving the property, and of the survivors of the shooting as well as relatives of those killed, who disavow any racial motivation -- to go beyond the headlines of the day.

What was your goal in making the film?

MT: Well, I guess the initial goal was very naïve, very ambitious. I think this was symbolic of what was happening in America, especially in the heartland, where we’re still 98 percent white, especially the rural areas of Wisconsin. The initial impulse was, wait a minute, there’s a lot more to this than what we hear in the news. Let’s go out and get all the voices but also make sure that this is going to be balanced, that the voices are not just from people of color or from the city. We knew one of those voices would be we don’t hear that often are rural voices. We need more balance to give more context to the larger issue at hand.

LL: Of course the overriding goal was to create more understanding so that this kind of incident, this kind of racial harassment, in particular in this area of hunting [won’t continue] because it’s just been nonstop for decades, even before the Hmong were here. And then there’s all this antagonism with Native Americans and fishing rights.

Rural Wisconsonites and probably Minnesotans, too, are very hostile towards the Hmong about the hunting issue. For them it’s all about trespassing. And when the Hmong first got here they have different concept of what that was going to mean. Now I think the facts of the case, young Hmong hunters now know the same rules as everyone else.But there’s still lingering suspicions, lingering antagonism, that the goal of the film is trying to ameliorate.

Were there any surprises when you were shooting the film?

LL: I came to understand more about people that I -- let me put it tactfully -- people that I thought were racist assholes, how’s that for tactful? This idea of how much these people hate to be called racist and they absolutely refuse that designation. And we’re thinking, how could you say that? That’s so stupid. But to understand where their sentiment is coming from, how they can think such a thing and not just say, yeah we don’t like Hmong.

MT: I don’t have any surprises. But the thing is that this film would not have been made without the support of both the Asian American community and the white community, you know. Where it happened was at least two hours from the Twin Cities so we’re not local. And it’s after the fact. It’s really like pulling teeth to get people to talk and we don’t have any contacts in the rural community.

But you can’t generalize the rural area. Look what happened at the capital, union busting. You have very progressive people, you have Green people and you also have the hunters, the people who would put down Native Americans because they push for treaty rights. So you have a whole gamut of people. I’ve been in Minnesota for 20 some years, people know me in the community so Chai Vang wanted his story told. He was the one who contacted me from jail. He wanted to talk [to me] before he talked to the Chicago Tribune reporter. But I was always leery of just showing my face in Rice Lake [near where the shooting occurred] and knocking on doors and calling people, “Hi, this is Mark Tang, I know your son has been shot.” So we kind of circle around the wagons in a way.

We didn’t want to bother the direct families [whose relatives has been killed], we wanted to go through friends or pastors or something. But eventually the duties are split in the middle where Lu Lippold, a name known all over Wisconsin, she’s the one to contact the so-called victims families and I am the kind of person the [Hmong] community trusted enough to want to talk to. I tried to stay behind the scenes when we go to Rice Lake where I’m just shooting.

LL: I guess I was naively surprised that this was kind of like the O.J. trial in terms of racial interpretation of it. I was surprised at how much people [in the Hmong community] didn’t want to hear anything negative about Chai Vang. They didn’t want to hear that he had a violent past or anything. He had this folk hero thing.

What were the biggest challenges in making the film?

LL: Getting the frickin’ money to finish the frickin’ thing.

MT: The main thing is getting people to talk. It’s easier to get people who wanted justice, like Chai’s sister, the community. Whereas any white, even liberal whites, you don’t want to be on camera saying, we know this thing has been going on because they have to live in their community, you know. The last thing anyone wants is to be called racist. They would rather be called murderer. So it took us two years to get to the victims families.

LL: I called all the people, everybody, all the relatives and eventually, those were the two who ended up speaking. It’s just hard talking to people who are grieving.

MT: Prior to this I wasn’t privy to the hunting world, which is like the mainstream population. We didn’t know there had been [long existing] tensions. Part of the reason I wanted to do this film is there is all this tension building up. After this thing happened, we talked to some people and everyone said, we knew something like this is going to happen. But other people just didn’t know. Prior to [the shooting], I loved going to Wisconsin, the beautiful scenery, going to the island by Lake Superior, but now I’m super cautious. I don’t want to go by myself.

This is another dichotomy. We want immigrants to come here to be assimilated, be part of America, speak English, do this, do that. But when you go out there, fishing, hunting, and so on, it’s like, ok these people they’re tramping all over. We’re all immigrants. Wisconsonites are descendants of German Americans and whatnot from the old days. In the end because we’re cutting this within one hour for a national audience, we didn’t have enough time to get the larger issues in. We had just enough time to tell you what happened, who, when, you know and the progression of events.

LL: Luckily other people are writing books about it and writing plays and making narrative films so they can cover all the other stuff.

Chuleenan Svetvilas is a writer and editor in Berkeley, California. Her writings on film have appeared in Alternet, Documentary, DOX, Mother Jones, and in the book Soccer vs. the State, edited by Gabriel Kuhn (PM Press, 2011).

Comments