Russell Brand, unpredictable and offbeat comic and husband to pop diva Katy Perry, is celebrity’s newest convert to Transcendental Meditation: an Asian-based spiritual practice popularized by Indian yogi Maharishi Mahesh in the 1960s. The coupling of Brand and Transcendental Meditation seems oxymoronic at best. But as the New York Times reports, Brand feels “Transcendental Meditation has been incredibly valuable to me both in my recovery as a drug addict and in my personal life, my marriage, my professional life.”

The Oriental Monk who made this all possible is the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Those who remember him from the 1960s and '70s remember his long flowing hair, unruly beard, bare feet, wide grin, and brown skin. The dhoti-clad guru and his infectious giggle seemed to reflect the ethos of the hippie generation particularly well (“Enjoy! Enjoy!”). Maharishi’s face graced the pages of Time and Newsweek and his image became iconic for a generation.

American engagement with Asian religions has earlier precedents -- from Hindu and Buddhist influences in the works of Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman to spiritual leanings of Theosophist Annie Besant. Widespread knowledge and acceptance of Asian religious alternatives did not take root, though, until the mid-20th century and especially during the seminal decade of the 1960s.

So how did the American fascination with meditation, yoga, the Dalai Lama, or even Mr. Miyagi and Yoda come about? How does an Asian religion gain entry into the American cultural imagination? Viewing Americans’ fascination with “Eastern spirituality” from this historical vantage point, we might offer the following pointers.

- Have an icon. A focus on a specific guru or teacher -- an “Oriental Monk” figure -- is key. His philosophy and outlook are important; but perhaps more significant are his Asian face, mannerisms, and style of dress. Such visual cues help authorize an Asian spiritual movement and practice.

- Networking, networking, networking. The Oriental Monk has to have celebrity friends. Asian religions really gained exposure and popularity when D.T. Suzuki and Zen Buddhism were embraced by John Cage, Beat writers, and the New York art scene. Similarly, the Maharishi capitalized on his association with the Beatles, Mia Farrow, and the Beach Boys. And of course, we are all familiar with the Dalai Lama and his celebrity network.

- Be user-friendly. The successful Oriental Monk must market his views and practice as something that requires minimal time and energy and easily conforms to one’s lifestyle. It should make little demands on the practitioner and be easily consumable. Religious commitment is not really a factor, since these Oriental Monks present their spiritual alternatives as universally inspired, scientifically-based, or solely philosophical. Asian-inspired religions in the Oriental Monk’s entrepreneurial hands and within the American imagination become no religion at all.

I am being a bit facetious here. However, historical research and current events demonstrate that my observations are not completely off the mark. The newfound spirituality of Russell Brand fits all most of these characteristics. First of all, it is easy. Transcendental Meditation “prescribes two 15- to 20-minute sessions a day of silently repeating a one-to-three syllable mantra, so that practitioners can access a state of what is known as transcendental consciousness.” No sweat.

TM has celebrity endorsements. Aside from our latest religious trendsetting celebrity there’s also Clint Eastwood, Moby, Jerry Seinfeld, Russell Simmons, Howard Stern, and of course TM’s most engaged spokesperson, David Lynch. Lynch, who began meditating in the late 1960s when TM was all the rage, founded the David Lynch Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education and World Peace (DLF), to introduce TM in public schools, prisons, homeless shelters, and among Native Americans and military personnel. He continues the tradition of star-powered spirituality begun by the Maharishi himself. TM officials deny the influence of their famous followers, though. Robert Roth, Vice-President of Lynch’s foundation protests that, “No one is going to meditate twice a day because a Hollywood filmmaker is doing it.” Sure. At any rate, such celebrity networks and the media attention they draw have kept the movement alive.

But Mahesh is strangely absent from Transcendental Meditation’s most recent incarnation. His likeness appears nowhere on the David Lynch Foundation website (a brief reference to the yogi is tucked away in a FAQ). And the official TM website is not much better. Mahesh’s image appears as a small icon at the top of the homepage, indicative of his shrinking significance.

It's Asian religions without Asians.

Now you can say that Transcendental Meditation was never an Indian religion (or a religion at all, as some of its followers would argue). That the Maharishi always had global ambitions or (put more nicely) universal appeal. Or that the contemporary movement seeks to distance itself from a leader whose image is plagued by suspect motives and material concerns.

All these statements are true. However, the bigger picture remains. Western practitioners appropriate what they want and need from Asian religious traditions. While TM proponents might eschew any formal connections to an established faith (most notably Hinduism) and downplay the Vedic roots of its practice, they certainly enjoy the thin veneer of Asian-ness that coats the movement. (A large part of TM’s attraction is the “mantra” -- a term imbued with Eastern mysticism and intrigue.) Asian-ness is invoked at will.

Ultimately, the Oriental Monk or guru is seen as a remnant of a dying (or dead) civilization: the last of his kind. Those in the West (à la David Lynch or Richard Gere) see themselves as the only ones who are able to appreciate the Monk’s ancient wisdom and as the tradition’s appointed heirs. Asians and Asians American certainly are not fit to play a prominent role. Or so the fiction goes.

Asian Americans have tried to challenge this narrative, along with the decoupling of Asian religions from the rich traditions from which they emerge and the vibrant ethnic communities in which they are practiced. Most recently, the Hindu American Foundation (based in Minneapolis) launched its “Take Back Yoga” campaign aimed at reconnecting the meditative practice with its Hindu roots and context. The campaign provoked a strong and often vociferous response. While the HAF’s essentialized re-presentation of yoga may also suffer from a lack of historical nuance, the Indian American organization does rightly point out the erasure of Asians from the larger religious picture.

The truth of the matter is that Asians have carried their religious traditions to the US for well over a century and continue to maintain thriving Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, and Muslim communities. But again, this presence is rarely seen or highlighted. Instead, we have to settle for a single acclaimed Oriental Monk at a time, who serves to make the movement legitimate but is eventually made obsolete and fades from the American scene. The Maharishi died in 2008, but he has been reincarnated as David Lynch -- still quirky, yet wholly assimilated for the American scene.

* * *

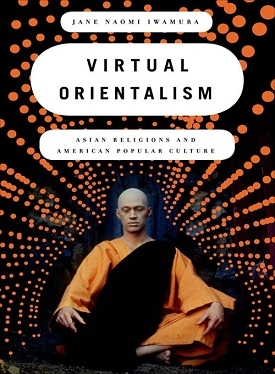

Prof. Jane Iwamura is the author of Virtual Orientalism: Asian Religions and American Popular Culture (Oxford, 2010). She also co-edited the volume Revealing the Sacred in Asian and Pacific America (Routledge, 2003).

You've just read a post from Across the Desk: a collaboration of Asian American journalists and scholars. See here

for more in the series. Scholars and journalists interested in

contributing, please email the series editor at

erin[at]hyphenmagazine[dot]com.

Comments