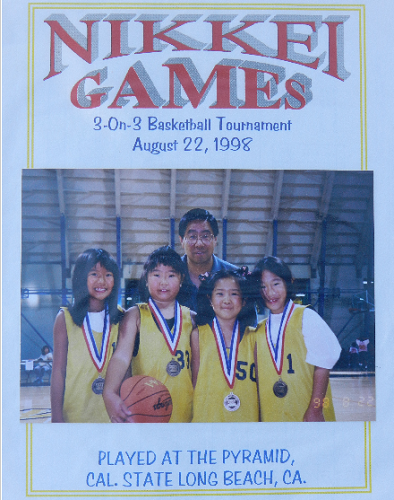

Photos courtesy of the author

If you're Japanese American in my

slice of town, playing basketball is like a Nike commercial: you Just Do

It. Parents start us off young; I

started playing in kindergarten. That's

right -- while I was still learning to count to 100, a basketball was put in my hands

and I was taught the rules of the game: how to dribble, pass, and shoot a

layup.

Perhaps

I should explain. Ever since I can

remember, I’ve been a part of the South Bay Friends of Richard (FOR), a basketball organization founded in 1959 to honor Richard Nishimoto, a Japanese American passionate about

sports, who met an untimely death at 18. The organization started as a single team, with 15 boys, but now tallies

over a thousand participants, from age five, up through high school, and

beyond. In Torrance, it's just what Japanese people do.

FOR

is no small thing. With an annual tournament

that runs like clockwork (my family automatically marks off the first weekend

in May; we already know it'll be spent in the gym), clinics for other sports,

and even a scholarship for high school seniors, FOR offers opportunities for

community members to coach, play, and volunteer. Up and down

California, it's a Japanese American phenomenon,

the birth of the “Asian Leagues” (see here for why). Most

leagues started off with just Japanese American participants, but recent

years have seen a more mixed makeup. Each league has its own

teams, broken into age groupings and gender. Our organization played teams from San Fernando Valley, Venice, West LA, and beyond. Each city has its own Asian League

organization (and reputation).

I

played through my senior year of high school. That's right; thirteen long years with the court, the fans, and a

bouncing orange ball, in my blue and white jersey as a part of the FOR No Ka

Oi. But don't be too impressed. Just because you play forever doesn't mean

you're any good.

Although

I may have left the gym with an average of a single basket a season, and only a

few steals and rebounds to my name, I became part of the community. Unlike most city recreation teams, Asian

League teams stay the same year after year, so I knew my teammates well -- I

literally grew up with them. We played

year round, so there was always a tournament or league to practice for. I spent my nights and weekends with these

people. Even if we didn't go to the same

school, I still saw them for two hours every Thursday night at the gym for

conditioning practices, an hour and a half Saturdays to go over plays, and religiously on Sunday game days.

Sound crazy? I'm not exaggerating. One of my teammates was the youngest daughter of three. Her family spent two decades with FOR,

carting girls to practices, sitting in the stands watching games, and taking

turns making snack bags for after. Her

father, Uncle Phil (because, you know, in your Asian group of friends, you

always call the parents Auntie and Uncle), owned Rascals Teriyaki Grill, which always closed on

Sundays. Not for the love of God, but

for the love of Basketball. FOR was that serious -- people went to gyms,

not churches; they studied score boards, not Bibles.

As for me, although I wasn't a star by any means, I played on a very competitive

team. For a few years in middle school,

we were the best of the best. We had a

different tournament every weekend, taking us from the South Bay to Los Angeles, Orange

County, even San Jose and Sacramento. Tournament weekends were two long, sweaty Saturday games and a final,

stressful, all-important game Sunday. First place here not only bagged bragging rights, but also the traditional

prized black shirt of champions, and every weekend brought a different

organization’s tournament, with the prospect of yet another glorious black

shirt.

I grew up in this world

of unrelated Aunties and Uncles, where children introduced themselves first by name,

then by the team they played for.

Leaving my little FOR circle and coming to the big world of UCSB, I

found few people could relate to the concept of Asian League. People played high school sports, or were in

band, but none knew of FOR or like entities.

The closest I could explain was that Asian League was similar to Girl

Scouts -- a team had collective goals (logging baskets or Thin Mints), we all knew each other (on our team, not our troop), and

all showed off our earnings (instead of sashes filled with patches and badges

and pins, a player was measured by the depth of her championship shirt

collection).

For

over a year, I was a lost combination of some sort of FOR

Gaucho. Not until I met other Japanese

Americans at a Nikkei

Student Union meeting

did I reunite with my past. Somehow the talk turned to Asian League basketball.

These strangers, two years older than me, three years younger than me, from all

over California, magically knew about gym rats and Sunday games, the

coming of age signaled by growing out of snacks after games, the wonder of

showing up half an hour before game time just to put on shoes and ankle braces.

We swapped gossip. I heard Orange County

kids talk about how San Jose was full of mean girls and underhanded

coaches. I told of how my friends and I

would go to the FOR Tournament-sponsored dances at the Torrance Marriott and

throw dinner mints at boys we had crushes on. We reminisced about team pot lucks and the goodies made by Japanese moms

trying to out-cook each other.

In

those sixty minutes, I realized my own Asian League experience far transcended

the little 150,000-person neighborhood it started in. In that room, I saw people who grew up with a basketball in their palms, and the

perpetual lifetime fallback Halloween costume of a jersey and shorts. In any number of rooms, I may meet people who played past their prime years of high school, and would be playing basketball

long into the years of salt and pepper hair and knee braces. FOR shows that beyond love for a sport, basketball can build a community, and be so much more than

a game.

* * *

Alyctra Matsushita is a student, reader, and occasional writer. She enjoys rainbow sherbet, lighting candles, and sun dresses.

Comments