Tom Serafino, age nine, tells his twin sister, Teagan, to

“Get out of my life!” Shortly afterward, Teagan falls into a pit and suffers a

debilitating brain injury. The boy who dared her to jump, Mario Guzman, panics

and runs away. Mario’s uncle, a transient immigrant worker called Shoe, discovers

the girl in the pit, along with his nephew’s football. He stashes the football

away to protect Mario and later allows himself to be implicated in the tragedy.

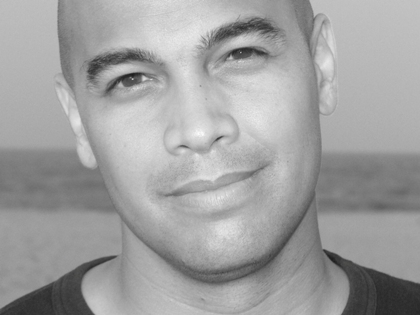

This is the series of events that launches Jon Pineda’s

debut novel, Apology, winner of the

2013 Milkweed National Fiction Prize. The novel explores the deeply felt

consequences that ripple around Teagan’s accident, for her brother Tom, Mario,

Shoe, and for the people connected with them. It is a beautiful and compelling

read.

The novel is told from multiple points of view: primarily

those of Tom, Mario, and Shoe--or his real name, Exequiel. Each character is

revealed as a complex, flawed human being. There were moments in this book that

were simply too heart-wrenching, yet you will find yourself reading on because of

the sympathetic portrayals of each character.

As the novel unfolds, we are shown scenes from the Serafino

and Guzman families as Tom and Mario grow up. The two boys progress through

middle school, graduate from high school, and become adults, meeting all the

usual milestones while Teagan--mentally and emotionally--remains a child.

Nights, Tom lay in bed and glanced over at

the B-52 that was forever grounded on his dresser. He could imagine, as the lawyer had posed the question that day, but

when he did now, parts of his life pulled away. Were swept up and scattered. He

thought hard for Teagan, too.

The future had become a distant,

unattainable target.

Sometimes he would hear her down the

hall. From her room, she would be yelling and, if she was especially upset,

beating one of her dolls against the wall.

In the morning, at breakfast, he

would find her at the table crying over the doll’s broken face. Inevitably,

their father would come home later in the evening with a wrapped present, and

she would never be able to guess what was inside. Until the paper was finally

torn back and her face grew bright, full of such honest surprise, it made Tom

catch his breath.

Jon Pineda

Pineda is the author of two collections of poetry, and Apology has a definite poetic aesthetic.

His prose is spare and precise, with a lovely, natural sense of rhythm and

pacing. The narrative is written in

short segments with intervals of white space; there is much that is left

unsaid, such that the writing never veers into sentimentality, even as it is

pregnant with emotion. In an age dominated by Hollywood over-writing (Bella

sobbed desperately), I found Pineda’s

spare narrative style very compelling. Rather than following a chronological

plot, the writing gradually reaches a core that is unwrapped layer by painful

layer, and it is in the white space--as in poetry--that the reader is allowed

to feel the raw complexity of emotion.

The anchor of the novel lies in the character of Shoe/Exequiel.

His fate is not a surprise, but the reckoning of his past is the heart of the

novel; these are the events, decisions, and regrets that formed him into a man

who sacrifices his life to protect his nephew and family. There are many

regrets for which Exequiel desires forgiveness, including leaving a girlfriend

and her young boy who had grown attached enough to him to call him, “Dad.”

The following passage takes place as Shoe/Exequiel considers

what to do after Teagan’s accident:

He realized then he

should have just left things in place. He should have climbed out of the pit

and run as best he could with his foot as it was and found a phone, any phone,

and called an ambulance directly. He wanted to go back in time and make a

different choice.

Or go back even

further.

Back to a time when

he was still a boy in another country. There were no hard questions, no actions

to take other than waking and surviving and laughing in between those moments.

He could barely see his nephew’s face. He knew his presence in this boy’s life

had compromised the situation.

Worse, still, was

having left the child. Not that he could have saved her himself, but he could

have been the one to save her. Maybe his life could be different if only he had

a way to get back to certain moments. He could still hear a boy from another

life saying, Check, and then laughter

when Shoe looked bewildered at the chessboard.

Both the Serafino and Guzman families are first generation

immigrants from the Philippines and dislocation is a constant theme running

through this narrative. From Exequiel’s transience to Tom’s pledging with a

white fraternity to Mario’s meticulous memorization of the human body, these

are characters who feel uncomfortable in their own skin. You will long for them -- as they long for

themselves -- to find home, somewhere to rest their weary heads and feel whole.

Apology may be a

first novel, but it suffers from none of the usual first novel flaws such as fuzzy

characterizations or hurried plots that feel like an editor rushed a manuscript

to publication. Apology feels like it was written on its own terms, on its own

time. Pineda is a writer who knows his craft and lives his characters; this is

evident from the first pages of his book. There was never a moment that felt

like a misstep or something that didn’t ring true.

There are no easy answers in Apology; there are many questions and much honest searching. What I

admired most is how the spare narrative allowed me, as the reader, to feel my

own feelings and respond as a human being. It is a rare book that connects me

to its characters so deeply.

Sabina

Chen reads, writes, and chases after her toddler

Comments