Thi Bui’s beautifully illustrated memoir The Best We Could Do is a story of origins: her son’s birth, her family’s escape from Saigon after the fall of South Vietnam and her childhood and young adulthood in the United States. With stunning visual eloquence, Bui depicts her family’s boat exodus from Vietnam and their eventual resettlement in the United States, alternating between past and present on a journey that spans three nations and four generations. The book makes a notable contribution to the growing body of recent work by Vietnamese American writers who have garnered prestige in the literary world, among them Viet Thanh Nguyen, winner of the 2016 Pulitzer Prize; Duy Doan, awarded the 2017 Yale Series of Younger Poets prize; and Ocean Vuong, 2016 Whiting Award winner. To a certain extent, The Best We Could Do also participates in what New York magazine essayist Kim Brooks calls “the literature of domestic ambivalence,” a genre of literary prose that explores the experience of contemporary mothering and its relationship to art-making. Yet Bui’s narrative both enriches and challenges this relatively homogenous canon, calling attention to the fact that to write a story about childbirth without acknowledging previous generations is to write with a kind of invisible privilege. Some of us, Bui’s tale argues, come from families so haunted by the specters of colonialism and military conquest that in order to write our own story, we must first write that of our parents -- and of their parents, all of which have been deeply implicated by larger histories of violence. With The Best We Could Do, Bui reveals the stitches and seams that painfully, with all the blood and anguish of childbirth, bind her family’s war-ravaged generations together.

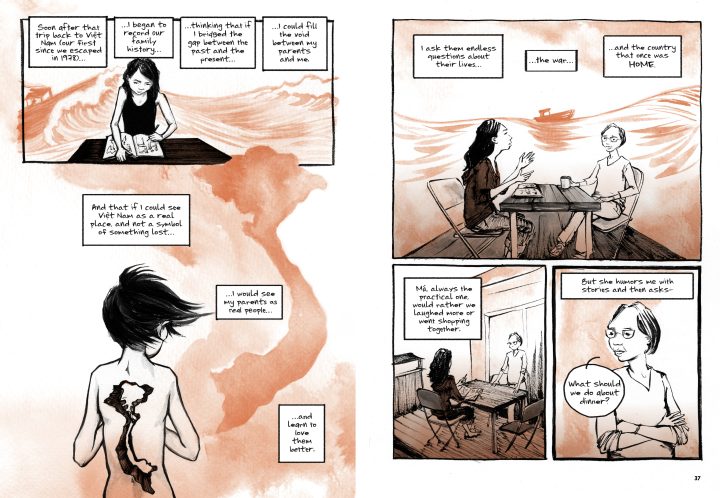

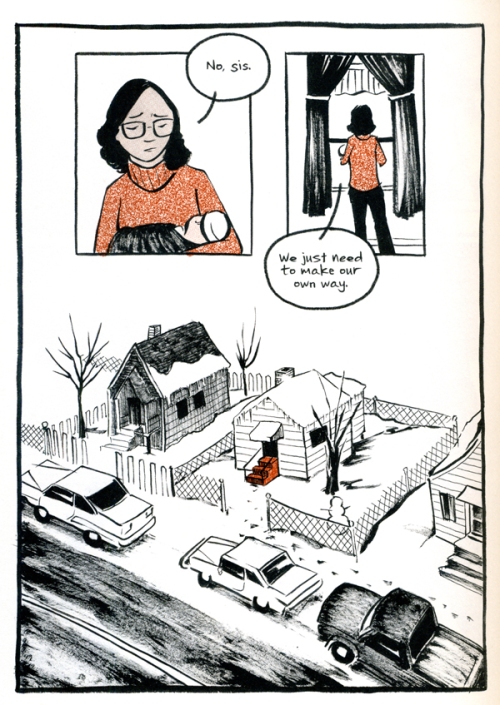

The book opens with a single full-page panel, a view of the author’s pregnant belly and the words: “I’m in labor.” What follows is a childbirth experience traumatized by a frightening array of medical interventions and the impersonality and brusqueness of the delivery ward. Yet this origin story, which culminates beautifully in the birth of the author’s son, a free-floating, delicately inked newborn rippling across the page, is only the beginning. “Family is now something I have created -- and not just something I was born into,” Bui writes, describing her desire to “trac[e] our journey in reverse … seeking an origin story / that will set everything right.” What does it mean to tell an origin story? And what does one make of origins that have been lost -- or forgotten? “Lacking memories of my own, I do research,” Bui remarks, as she follow her older siblings through their old neighborhood in Saigon. The expression on her face, when it emerges from behind her camera, is distant and somewhat bereft, as though she has misplaced something but doesn’t know where to look for it. This memoir represents Bui’s efforts -- as an artist, a graphic novelist and a family historian -- to rediscover her origins through the distant saga of her parents’ lives: their disparate childhoods under French colonial rule, the foment of their revolutionary consciousness and their tumultuous, ill-fated romance. Over the course of the book, she traces the complexity of their evolving relationships with one another, interlacing her parents’ stories with frames of herself on walks with her mother or seated across from her father, microphone and voice recorder in hand. Later, Bui depicts her family’s passage to Malaysia and ultimately to the United States with unflinching realism, an account that, given our current political situation, is wrought with heartbreaking relevance.

In the closing chapter of The Best We Could Do, Bui comes to a new understanding of her past, her experience as a first-time mother bringing clarity to her relationship with her own parents, as well as to her identity as a Vietnamese American. As she sits nursing her infant son, she writes, “I could hear echoes of my mother’s voice speaking to me in my childhood … but I could feel the voice coming from my own throat.” It’s a moment of profound feeling, underscored by the powerful physiology of the let-down reflex, a hormone-induced response that triggers the flow of milk from breast to child. Bui lingers here for several frames, reveling in the body’s sustaining miracle, and how life, when offered freely from one generation to the next, can become an act of healing. War has a long memory, and trauma has a half-life that lasts for generations, but so does the human spirit -- its courage and indomitable will to survive, which lives on to be passed to the next generation. In this way, The Best We Could Do is a deeply American story, tapping into the national myth, however illusory, of freedom in new beginnings. According to Thi Bui, the choice is ours -- to respond with cynicism or with renewed commitment.

Comments